(MENAFN- The Conversation) COVID-induced school closures in 2020 meant that the majority of pupils in England, at the first and secondary levels, missed around 40 days of face-to-face schooling. Schools around the world have been affected in the same way. , but to other degrees.

As recent figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development show, in the first 12 months of the pandemic, 1. 5 billion academics in 188 countries and economies were unable to move into school, for varying periods of time. The Netherlands and Ireland are on a par with England. In Denmark, academics missed nearly 20 days, while the numbers are much higher in Costa Rica (nearly 180 days) and Colombia (about 150 days).

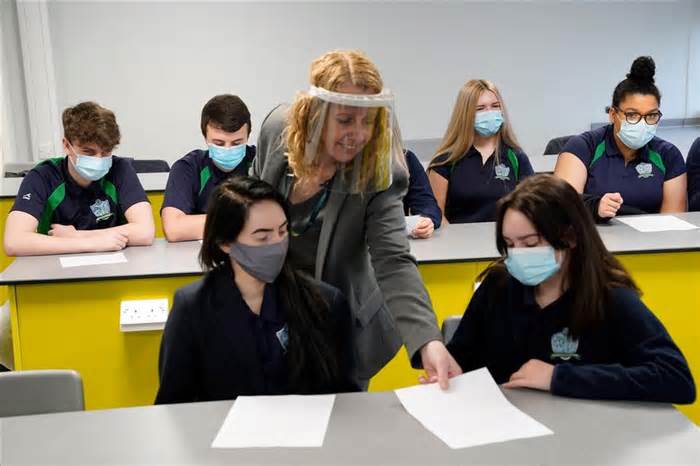

Although most English schools at the time featured some form of distance learning, those closures led to learning losses. As a result, as part of the UK government’s plans for post-COVID school recovery, the Uncomponent for Education has reportedly discussed extending the school day, in all likelihood the existing cap on the number of hours public school teachers can be asked to work will be removed.

International evidence suggests that, in some cases, a longer school day could possibly be beneficial. A report by the United Nations-led Task Force on Accelerated Education has proposed several tactics to address pandemic-induced learning losses. Training time for the implementation of formal remedial programs with remedial categories for students with difficulties. Longer training time has been proposed as an appropriate strategy when students have missed up to a year of instruction.

In addition, studies such as those conducted in the United States, Canada, and Chile raise the concept that extending instructional time can help students, either in the short or long term. They would gain academic advantages (in terms of achieving higher test scores and higher educational attainment) and socioeconomic advantages (their long-term source of income would be higher).

However, research from studies conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean found that, despite those benefits, there would possibly be more effective tactics to achieve similar results. An additional and vital focus would be the mental load of teachers.

Of course, a longer school day means more hours of training. And this raises the question of whether asking teachers to extend their working hours is a moderate request.

Under government guidelines, teachers in England’s public schools would possibly be required to teach up to a maximum of 1,265 hours over 195 days a year. This number does not include responsibilities such as course scheduling, evaluation, tracking, recording, and reporting.

Data from four surveys shows that before the pandemic, the average full-time instructor in England worked 50 hours a week and around 4 hours a week on holiday. In fact, there are outliers, with 10% of full-time instructors reporting working at least 30 hours per week during summer and midterm breaks and 15 hours during the Christmas holidays. The researchers also found that the number of hours painted had not decreased in 25 years. In fact, it has been found that teachers in England paint longer hours than in most other countries, with fewer secondary school teachers working around 8 hours more per week.

Our ongoing studies of what it’s like to be a teacher during the pandemic show that teachers are feeling frustrated. The participants we interviewed expressed dismay at the way their career was portrayed by the media and some of the public as lazy.

And the numbers show their frustration at this mistaken impression. A survey conducted in June/July 2020 through the British charity Education Support found that 31% and 70% of bosses reported running more than 51 hours a week on average.

Since March 2020, many teachers around the world have had to oscillate between partial school closures, partial reopenings, and full reopenings. To adapt, they had to temporarily learn new skills so they could teach their students from home.

They also did much more than just teach. They called and, in some cases, visited academics and their families to assess and address their educational and social needs. Given the current uncertainty of the situation, it is not unexpected that we have noticed the intellectual aptitude and well-being of our participants. Teachers get worse throughout the pandemic.

While lengthening the school day may have been advantageous for students, care must be taken with the costs to teachers’ intellectual fitness and well-being. Students would not benefit from schooling by exhausted and pressured teachers. For the recovery plan to be effective, it is vital to take into account the wishes and perspectives of teachers.

MENAFN13012024000199003603ID1107715790

Keywords

comment

Category

Date