Home in the World Global Economy

Alicia García Herrero (Natixis) *| China’s grand infrastructure progression strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has suffered from the COVID-19 pandemic, at least when measured through the amount of budget borrowed or invested through China in BRI projects. This minimal investment is one of the maximum visual symptoms of China’s developing isolationism and deteriorating global image.

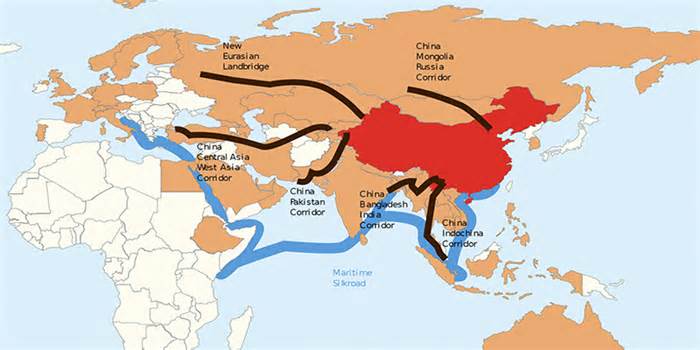

President Xi announced in 2013 China’s largest comfortable force strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Since then, it has gained economic and political prominence. In fact, the official number of countries included in the BRI has gone from less than seventy countries, in the six economic corridors announced first, to 149 today. Projects covered through this main strategy are higher not only in number but also in sectoral and geographical complexity.

However, as it gained relevance, the Belt and Road Initiative suffered a primary impact: the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the end of January 2020, China has closed its borders to the world, with significant consequences. In particular, the number of physical exchanges between China and the rest of the world has decreased due to draconian quarantine restrictions and rules.

At the same time, negative sentiment towards the Belt and Road Initiative, and China in general, has increased. This downward trend in the symbol of China has become even more pronounced during the pandemic and is most pronounced among evolved economies, as shown by a survey conducted through the Pew Research Center. In the same vein, the 2021 annual opinion survey conducted through ISEAS addresses the same phenomenon in Southeast Asia. Beyond general surveys, my own research of local and foreign media in a large number of countries, employing the large GDELT knowledge media platform, shows a trend of severe deterioration of China’s pandemic symbol. The same is true for the foreign symbol of the BRI, though less intensely than for China as a whole.

China’s trust in the West has also deteriorated. The fact that China has experienced a very low number of COVID-19 cases until recently has led to a strong sense of home security and clutter vis-à-vis the West. Several polls imply a sharp deterioration in China’s symbol of the West to 2016.

One important thing in China’s relief in BRI project investment is the very negative economic effect of the pandemic, first in China in the first months of 2020 and then on the global economy in general, which has obviously worsened the outlook for many of those projects. First, uncertainty is being generated about the long-term return of such projects given the scars of COVID-19 and the increasing number of sovereign defaults in BRI countries. China’s economy also wants more resources from its own monetary establishments to stimulate growth. , after falling due to zero-COVID policies and the bursting of the housing bubble, making it difficult to allocate monetary resources for overseas projects. In addition, the BRI countries themselves have shifted their priorities, moving away from primary infrastructure products to cushion the negative effect of the pandemic on their populations. They are increasingly reluctant to accumulate debt from infrastructure projects at a time when financing prices are rising.

In such a context, there is sufficient evidence of a large number of BRI allocations delayed or abandoned by the pandemic. According to a report by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), more than fifteen allocations, valued at more than $2. 4 billion, faced monetary difficulties. In 2020. By insufficient, the allocation of electrical power from the Kunzvi Dam in Zimbabwe, first subcontracted to Sinohydro, ran into difficulties due to Zimbabwe’s non-compliance. pay a commitment payment in USD to China Export

Looking at the evolution of Chinese outbound investment during the pandemic, according to the knowledge of the American Enterprise Institute and Mergermarket, the slowdown in China’s foreign investment in the BRI countries is very clear. China’s outbound investment rarely includes control, through foreign direct investment (FDI), business acquisitions, or entirely new investments, where corporations build factories from scratch. However, more often than not, China only lends and does not hold shares, adding through allocation funding. mergers and acquisitions (M

In other words, the BRI geographies have never won the bulk of China’s outward FDI; China has truly invested the most in the West, whether through corporate acquisitions or greenfield investment. All BRI regions saw relief in FDI from China; however, the slowdown was stronger in the Middle East and emerging Asia than in Latin America or Africa. Latin America is an exception, as it has gained relatively more FDI, rather than just loans, although it turns out to be the region most affected by the pandemic, as evidenced by the greatly reduced maximum mobility vitality of its residents, and therefore . with the maximum negative economic impact. China’s interest in obtaining assets in Latin America compared to other BRI geographies may only be due to the preference of Latin American governments to privatize assets, especially public services, in order to gain fiscal space to mitigate the economic effect of the pandemic. Most of the M&A deals announced in the past two years are privatizations of state-owned energy or resource extraction companies, such as State Grid’s acquisition of a 96% stake in Compañía General de Electricidad S. A. in Chile and the acquisition through Yangtze Power of 13. 5% of the Comparte. of Luz del Sur SAA in Peru, to Mergermarket’s knowledge. In summary, business acquisition from China has slowed globally, adding to the BRI geographies, with a less marked decline in Latin America, due to the region’s divestment of state assets.

As for China’s loans, progressive financing in BRI geographies has declined since the pandemic began. This is especially problematic for countries that rely heavily on Chinese loans to finance their infrastructure, some of which have existing developing account deficits that they will want to finance. An apparent example is Sri Lanka, which recently opted to default on its foreign debt, which is largely made up of Chinese loans.

The key question here is whether the sharp slowdown in BRI-related investment and lending in China is only transitory and therefore bound to resume as the pandemic becomes rampant. On the face of it, a recovery to the pre-pandemic reversal point is very likely as China deserves, in principle, to remain interested in the same strategic goals it set for itself in 2013 when it introduced the BRI: building a global infrastructure to bring China closer together. with the rest of the world, selling off Chinese exports, reducing its excess capacity, and editing China’s comfortable power. One can simply argue that China deserves to be even more motivated to announce BRI projects than it was in 2013, to avoid potential isolation resulting from US pressure to involve China. In such a context, the BRI looks like a well-established platform for China to expand alliances and partners abroad. Beyond the US’s search for like-minded partners, another possible source of festivals comes from the European Union, namely its new €200 billion Global Gateway project, which aims to help the EU bring carry out sustainable physical and virtual infrastructure projects abroad. .

Although increasingly vital for China, there are two significant constraints that may jeopardize the continuation of the BRI, at least in terms of its initial definition and scope, as envisioned by President Xi. First, China is far from turning the page on the COVID-19 pandemic, at least compared to the rest of the world. His zero COVID policy, even in its existing dynamic form, further reduces trade. For example, annual air traffic between China and the United States decreased by 35% in June 2020 and as much as 86% in June 2021, compared to 2019. These trends have only worsened since then. More recently, the Chinese economy has been experiencing a very immediate slowdown due to draconian mobility restrictions imposed at the national level and specifically in Shanghai, China’s most important monetary center and the center of the supply chain, since the severe Omicron wave of the moment in the quarter of 2022. The slowdown is putting additional pressure on banks to lend locally rather than abroad. These loans are essential for financing primary infrastructure projects abroad. In addition, tighter control by foreign regulators, namely the United States, has limited the ability of Chinese corporations to raise hard currency funds, either through foreign stock exchange listings or overseas bond issues. .

It’s too early to say what the long-term of China’s BRI initiative will be once the pandemic ends. What is transparent is that the longer China remains locked within its own borders, the harder it will be to push for the same point of ambition with which President Xi presented this grand strategy. Chinese investment will remain limited, restricting the number of infrastructure projects the country can embark on. Restrictions on cross-border mobility will also hamper China’s ability to build overseas, as it relies on the use of Chinese labor. Similarly, China’s desire to refocus its monetary strength on the domestic market to revive post-pandemic expansion is diverting attention from new BRI projects. It hardens its stance and its economic scenario suffers the consequences of the pandemic.

Overall, among the many casualties the COVID-19 pandemic has caused, China’s grand strategy, namely the Belt and Road Initiative, could end up being one. resources invested in BRI projects, however, mandatory measures may go against the spirit of the dynamic zero-COVID policy, which remains the most sensible of Xi Jinping’s agfinisha. From the perspective of the beneficiaries, and given the huge debt they have already accumulated, China’s reduced interest in the BRI may be just a blessing in disguise at a time when financing for such giant infrastructure projects is far greater than when the BRI was launched. for such megaprojects given their burden and the emergence of new priorities in a post-COVID world.

Chirp