With the United States recording its highest deaths in Covid since May, political leaders and commentators are concerned about the long-term cities. Recent stories document covid’s negative effects in New York, namely how the pandemic accelerates and exacerbates racial and economic inequality. But New York has weathered worse storms than Covid, and while there are changes, cities like New York remain the main drivers of our economy. They want to be helped if the economy recovers.

Faced with a budget and a declining economy, New York is getting a lot of negative attention this week. Diversity of negative stories, from retail closures to imaginable municipal staff layoffs and fears of whether schools can reopen.

On Tuesday, the New York Times published an article titled “Retail Chains Leaving Manhattan: “It’s unbearable.” Citing restaurant managers, clothing chains and retailers, closures are related to the collapse of tourism, heavy discounts on commuter workers and jobs that they do, and the maintenance of higher advertising rents.

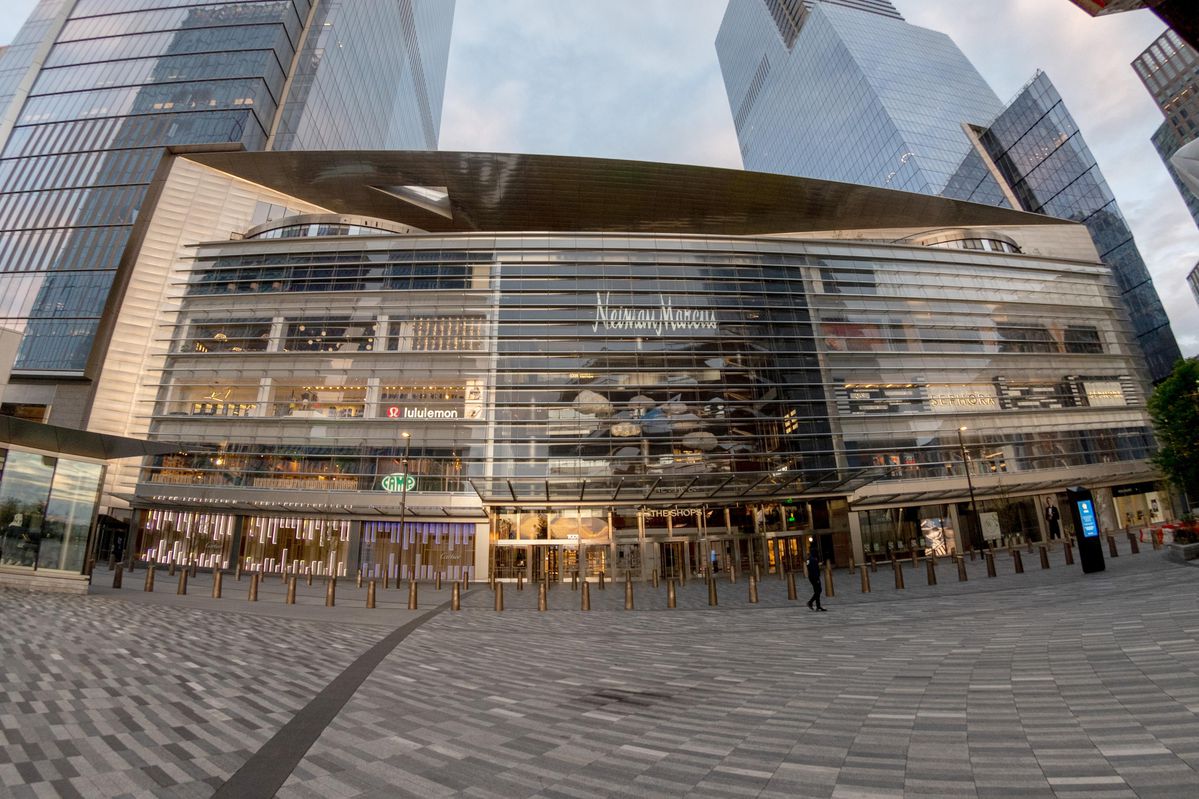

There is no doubt that paintings and retail are greatly affected by the pandemic. Advertising property rentals in major Manhattan corridors have fallen 11.3% in the previous year. In the dazzling new progression of Hudson Yards on the west side, iconic outlets like Neiman Marcus and other shops and restaurants are on their final doors.

The costs of the apartments also suffer, as others are presented for sale. According to StreetEasy, in July there was an 87% increase in new listings compared to last year, however, fewer sales and lower average costs for the apartments that were sold.

And suburban locations within commuting distance of New York are seeing a spike in prices. According to the National Association of Realtors, Kingston, New York, 100 miles up the Hudson River, recorded the nation’s biggest second quarter home price rise. When comparing this year’s second quarter home prices to a year ago, Kingston’s prices shot up 17.6%. A realtor there attributed the price jump to fleeing New Yorkers, saying “Every single deal I have is someone from Brooklyn or Manhattan.”

But it’s too early to wait for the deaths of New York or other major cities. Homes and retail rentals before the pandemic were unsustainable and needed to be corrected. Commercial rentals in New York fell for 11 consecutive quarters, a trend that began long before the coronavirus. Facebook, which allows most of its painters to paint from the pandemic home, has just leased 730,000 square feet in Manhattan, expanding its footprint to 2.2 million square feet “for thousands of painters in less than a year.” This is a big positive bet on the Manhattan workspace and long-term needs.

Several of the retail chains cited in the Times article, adding JC Penney and Le Pain Quotidien, filed for bankruptcy and experienced monetary difficulties before the pandemic. As a component of his own bankruptcy filing in May, Neiman Marcus is final only at Hudson Yards, but in Fort Lauderdale and Palm Beach. And as my colleagues at the Schwartz Bridget Fisher Center and Flavia Leite have documented, Hudson Yards’s progression itself has been economically viable and has depended on significant government subsidies since its inception, long before the pandemic.

It is clear that the evolution of retail models, namely online shopping, is putting pressure on retail stores. New York, which in terms of tourist and pedestrian traffic, is doubly affected by the pandemic, however, structural tensions existed before it hit.

But we simply don’t know what the long-term economic effects of the pandemic will be on cities. There’s a stir in dynamic cities. Sectors are developing and declining, and (at least in economically dynamic places) other sectors are being developed.

Real estate is overloaded in what economists call a “web” style in which emerging costs lead to oversupply, leading to a forthcoming slowdown and lower costs. In the 1990s, older workplace buildings in the Wall Street domain became residential ensembles (see this link to the glorious Museum of Skyscrapers). A recent RAND Corporation blog explains how workplace buildings in Los Angeles can become homes, and New York may continue to do so.

Until the pandemic is over and we have a vaccine, the long haul of cities like New York will be uncertain. There is no doubt that the pandemic is severely affecting major cities, highlighting and exacerbating the racial and elegant inequalities that already prevail in our metropolitan areas. My new school colleague, James Parrott, presents the figures in detail here, and shows how inequality in New York was greater before the pandemic accelerated.

But, as the eminent urban planner Richard Florida says, the “dystopian predictions” of the city’s death due to the pandemic “are only the latest in a long series of predictions.” At the end of the pandemic, he predicts that “we will look back and see that the list of the world’s major cities has changed.”

New York City is greatly affected by the pandemic, which accelerates long-term unrest of inequality, racial division and elegance, compounded by a political formula that concentrates unrest in the city as the suburbs disproportionately reap the economic benefits that cities create. This is one of the reasons Congress acts to provide budget assistance to New York and other cities.

But we don’t know what the long-term effect of the pandemic will be. And its worst effects can be mitigated if the federal budget and political assistance are provided on the scale that our cities, and our economy and our country need. President Trump’s executive orders are far from up to the problem, and without congressional action to help cities, we threaten a much deeper recession than necessary.

I am an economist at the Schwartz Center of the New School (https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org) with extensive public sector experience in the study of cities and states. I’ve been

I am an economist at the Schwartz Center of the New School (https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org) with extensive public sector experience in the study of cities and states. I served as Executive Director of the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, Undersecretary of Labor for Policy, Undercommissioned Policy and Research in the New York State Department of Economic Development and Deputy Comptroller of Policy and Management of New York City. I also worked as Director of Impact Analysis at the Ford Foundation. I’m writing an e-book for Columbia University Press on cities and inequality.