Advertising

Supported by

Guest Essay

By Atul Gawande

Dr. Gawande is the Assistant Administrator for Global Health at U. S. A. I. D.

The thing that has surprised me most since I began my job leading foreign assistance for global health at the U.S. Agency for International Development is how much emergencies have defined my work. The bureau I oversee focuses on reducing the global burden of mortality and disease and on protecting the United States from health threats from abroad. Our work is supposed to primarily serve long-range goals — for instance, eradicating polio (after 35 years of effort, we’re down to just a handful of wild-type cases in the world) and ending the public health threat of H.I.V., malaria and tuberculosis by 2030. But from the moment I started, more immediate problems have diverted time, attention and resources.

In January 2022, when I took up this role, Covid was naturally the most sensible priority. Then, in late February, suddenly came Ucrania. La Russian government invasion has cut off the supply of pharmaceuticals, attacked hospitals and the systems they rely on, and sparked outbreaks among displaced people, potentially endangering even more lives than Russian weapons. More than 100,000 HIV-positive Ukrainians, for example, have been threatened with wasting access to life-saving antiretroviral drugs. We had to act temporarily to help Ukraine find strategies to keep pharmacies, clinics, hospitals, and public health capacity running.

That same month, a case of wild polio emerged in Malawi, a major setback after more than five years without a documented case in Africa. In the months that followed, we faced deadly cholera outbreaks in more than two dozen countries, most of the world. spread of mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) and an outbreak in Ghana of Marburg virus disease, a fatal cousin of Ebola. By mid-2022, waves of political violence and climate-related missteps had led to the forced displacement of more than a hundred million people – the number ever recorded in history, leading to increased numbers of illnesses and deaths from overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, malnutrition, and loss of basic fitness services. Last May, the World Health Organization reported a total of 56 active fitness emergencies worldwide. a scenario that Mike Ryan, head of the WHO’s fitness emergencies program, called “unprecedented. “

This is now the trend: one emergency after another, occasionally overlapping, diverting attention from long-term public fitness goals. And there are no signs of slowing down. Displacements and activities such as deforestation have increased contact between humans and wildlife, and thus the emergence of animal diseases that spread to humans (the Ebola virus, for example, has been linked to bats as an imaginable source of spread). The threat of injury in the lab, causing an outbreak is the main fear as labs proliferate and protective measures are left behind. On average, between 1979 and 2015, more than 80 laboratory-acquired infections were reported each year, many of which involved transmission beyond the first infected, and not all cases were reported. Developing artificial virology has simultaneously generated new life-saving remedies (e. g. , mRNA vaccines) and made it less difficult for bad actors to turn infectious diseases into weapons of mass destruction.

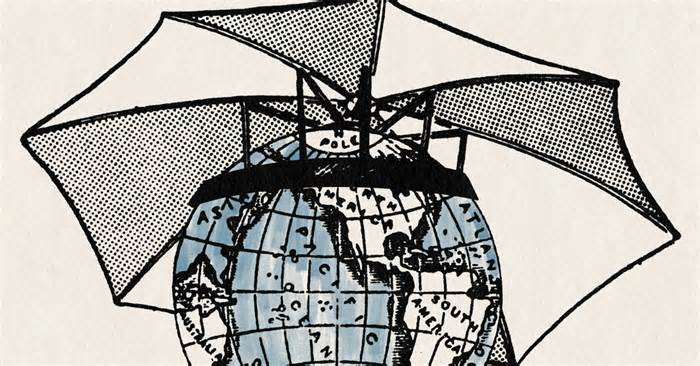

But we can break the pattern. Longer-term investments in local preparedness for such occasions – in building what I see as a global immune formula – can simply lessen the risk posed by such crises and even lessen dependence on foreign aid to deal with them. As the dangers increase, so does our ability to stay ahead of them. With the right strategy, we can simply use the incidents, wrongdoers, and shocks we face for our ability to adapt. It is not about building resilience (the ability to recover from a crisis) or solidity (the ability to cope with the crisis). It’s about developing what editor Nassim Nicholas Taleb called antifragility: the ability to emerge more potently from a crisis.

An example of this is our body’s immune formula: it detects and temporarily neutralizes pathogens before they cause catastrophic damage, while strengthening on exposure. Similarly, a global immune formula temporarily detects and neutralizes health threats before they cause catastrophic damage to the world. , while evolving and strengthening with the event.

Of course, the first line of defense against danger is to save it. Many members of the U. S. government are not aware of the fact that they are not in the U. S The U. S. has this task: we work with the WHO and partner countries to protect laboratories and safety standards, help studios expand vaccines against the danger. potential pandemic diseases and paints to prevent bad actors from emerging or spreading bioweapons. But saving it is never enough.

A global immune formula for speed will have to be constructed. Rapid detection that a type of disease could be potentially dangerous. Speed of diagnosis. Immediately alert public health officials and indicate the trace of exposure. Timeliness of patient care and preventive measures in the well.

Creating such a formula is a difficult task. Many communities face Herculean barriers to speeding up treatment, due to remoteness, poverty, civil unrest, or inadequate health care capacity. All those hurdles were overcome in December 2013, when a mysterious illness characterized through high fever, severe diarrhea, vomiting and a high mortality rate emerged in the West African country of Guinea. The disease circulated for 3 months before the correct diagnosis was made and an Ebola outbreak was officially declared. At the time, only 49 cases had been reported. But it took several months to find a good enough answer.

The Ebola virus has spread through the region, spreading through undeniable contact with the physical fluids and even sweat of people in poor physical condition. As the disease depleted local capacity and fitness staff succumbed, regular fitness facilities ceased to function. Businesses and schools closed. The economy has ground to a halt.

Soon, the disease reached Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. A traveler in Dallas inflamed two nurses and died. Ending the emergency took more than two years and required a global humanitarian response, involving the U. S. military. To date, 28,652 cases and 11,325 deaths have been recorded.

This burning crisis has spurred action for improvement. The United States has announced a partnership with countries in West and Central Africa to better prepare for outbreaks. YOU HAVE DIT. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has joined the WHO. Upgrade local lab equipment and train frontline fitness staff to recognize potential contagion. We have worked with government officials to identify emergency reaction centers and develop their public fitness expertise. We support the education of the network and devoted leaders about infectious dangers and how to deal with them. A faster regional immune formula was being built.

At first, the effects were hard to see. During a 2018 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Ebola virus circulated for 3 months before being identified. The reaction of the D. R. C. and its neighbors was better organized, but it was still characterized by significant gaps and delays. The disease was largely confined to the country of origin, but it took another two years and a gigantic global assistance effort to end the outbreak. There have been fewer cases (3,470) and deaths (2,287) than the outbreak that began in Guinea in 2013, but the numbers remain high.

As capacity and experience grew, however, the tide turned. In 2020, the D.R.C. had yet another Ebola outbreak, but this time it took local clinicians just 15 days to identify the virus. Government authorities responded rapidly and effectively, keeping the disease from spreading beyond the eastern region of the country. Instead of thousands of deaths, there were 55.

The experience of Ebola in Africa suggests that it is possible to achieve an effective global immune formula. But getting there requires a collective and sustained commitment to invest in the people and capacity needed on the front lines of care around the world. Despite our political differences and geographical divisions, the human race is off to an intelligent start.

Last year, the Group of Seven engaged with 100 countries that have not met foreign criteria for preparedness for biological threats. As part of President Biden’s National Biodefense Strategy, the U. S. government is tracking more than 50 of those countries. Since his first day in office, Biden’s leadership has worked with other leaders, the World Bank and the WHO. to create the Pandemic Fund, which has raised about $2 billion from 25 countries and philanthropic organizations. Last summer, the fund awarded its first grants to 37 countries for their pandemic preparedness. And this continued after the end of the Covid emergency. In December 2022, a two-component majority in Congress further increased investment in global pandemic preparedness and prevention, highlighting its importance in protecting America’s health and economy. This investment builds capacity, both domestically and globally, to more temporarily test, remediate, and vaccinate when and anywhere the early precautionary formula is activated.

We have a long way to go, there is no doubt. The onslaught of health disasters continues. A few months into my job at U.S.A.I.D., I determined that our Global Health Bureau needed an emergency department, the way hospitals do — a team dedicated to triage and rapid response. We call it our Global Health E.M.S. Now we in Washington are ready to move at faster speed when necessary, too.

And we’re starting to see what the speed of a global immune formula can do. In April 2022, I was informed of a new Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in a city of one million people on the banks of the Congo River. An elderly man who had been suffering from an emerging fever for a week presented himself at a clinic and died shortly after. But until now, the doctor on duty had acquired enough education to recognize the conceivable symptoms of Ebola. The medical team had the protective apparatus to protect itself, as well as good enough laboratory apparatus. They made the diagnosis and alerted the national public health government that same afternoon.

Within 48 hours, other people arrived to identify contacts, and newly developed vaccines were sent to those exposed. As a result, only five other people died. The disease never spread beyond the local community.

A reaction that once required years and many millions of dollars now took just a few days for a small fraction of the cost. This is what antifragility looks like. My team didn’t have to do anything. The country didn’t want any emergency aid.

Atul Gawande is a surgeon, public leader, and writer. Most recently, he is the Assistant Administrator for Global Health at U. S. A. I. D.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times op-ed on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X, and Threads.

Advertisement