New studies suggest that English speakers put more droplets in the air when they speak, possibly creating more likely to spread COVID-19. Because the new coronavirus spreads through droplets, the way the tongue was spat can contribute to the other rates of disease It all comes down to what we call sucked consonants, the sounds we emit and that spray more drops of saliva into the air.

In college, everyone knew which teachers spat the most when giving lectures. The first rows of their categories were empty after the first day of class, because the most sensible acting scholars who sat there had bathed in the teacher’s saliva. When a conference was really boring, academics could be mesmerized by the way sunlight stuck drops of saliva, suspended in the air around the teacher.

Memories of teachers who spoke aloud is one thing. However, we now know that only speaking English can mean that we all spit out the people around us.

We all know that coughing or sneezing spreads germs, which is how we get colds and flu every year. This spread occurs because coughing or sneezing throws high-speed droplets full of viruses from the nose and throat into the air around us. why we are told to cough in our elbows and wash our hands before Covid-19.

Then, the advent of the coronavirus pandemic led to studies that found that not only coughing and sneezing, but simply speaking resulted in aerosol viruses in the air. This is one of the main reasons why everyone is advised to wear a mask and stay larger than six feet. However, it turns out that not all speech effects have the same amount of drops in the air. Instead, it has the language used through the speaker.

One of the first indications that there might be a difference in the way viruses spread by language came here from comments made in China. Surprisingly, this did not happen with the Covid-19 pandemic, but the first SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in southern China The virus has caused more than 8,000 cases in 26 countries.

At the time, there were many more Japanese tourists than American tourists in southern China, however, the Americans accounted for 70 cases of SARS-CoV-1 and Japan had none. How can that be? At the time, an explanation from scientists was the language: because the staff of the Chinese store was multilingual, they spoke to American buyers in English while talking to Japanese tourists in Japanese, and that counts because English is full of sucked consonants while Japanese has few.

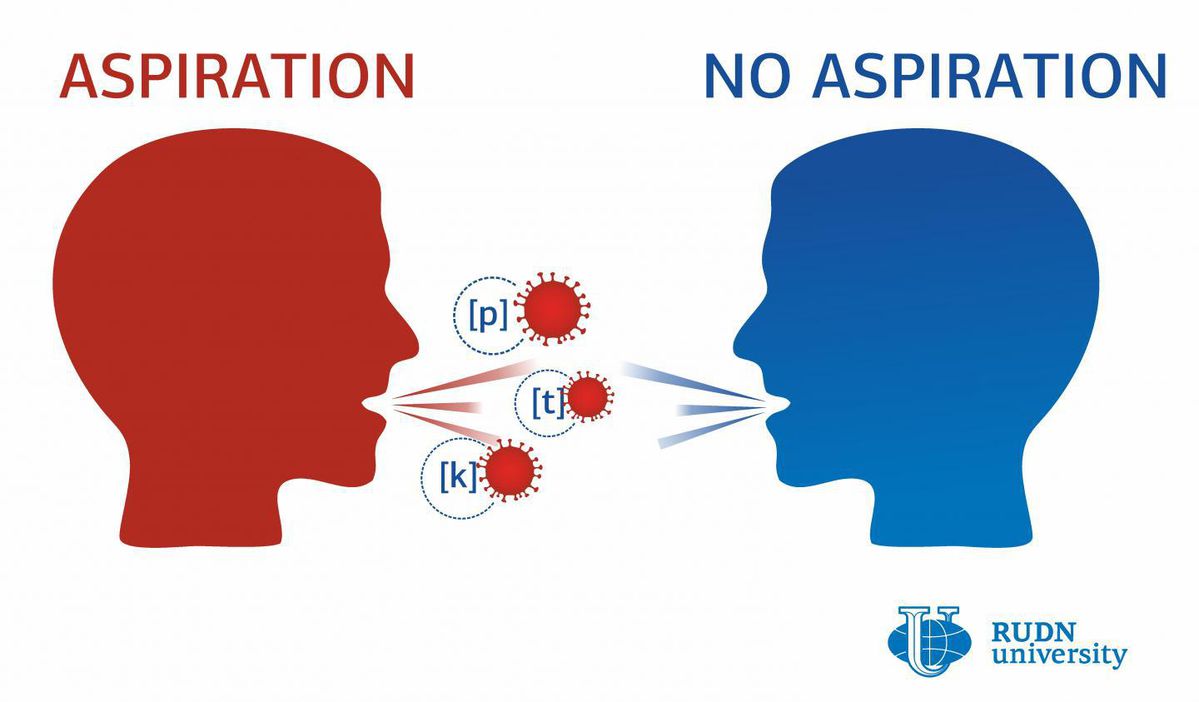

While Japanese has few sucked consonants, leading speakers to produce few salivations while speaking, English has three. Specifically, consonants [p] [t] and [k] are sucked in English. These sounds assign to the air a triad of tiny droplets from the speaker’s airways, creating a cloud of pins. If this user carries a virus, the air is now full of viral particles.

So far, a speaker’s perspective can be repugnant, yet we never thought it could endanger a fatal illness. Covid-19 replaced all of that, which is why RUDN University researchers have studied whether other people who speak languages with sucked continents have a higher rate of infection with the new coronavirus.

The review tested the knowledge of 26 countries with more than 1,000 instances of Covid-19 as of March 23, 2020. This is a useful time window as it would be before the use of the mask is generalized. Countries were grouped according to whether or not the basically spoken languages contained aspirated consonants. Knowledge included a large number of languages in addition to English.

In fact, there were more cases of coronavirus infection in countries that spoke languages with sucked consonants. These countries showed 255 instances of Covid-19 consisting of 1 million inhabitants, while countries where languages had few sucked consonants had 206 instances of Covid-19 consisting of 1 million inhabitants. Technically, these figures have not reached statistical significance, however, it is interesting.

The study cited experimental limitations, such as the formulation of hypotheses on the history of speaker language (which can also have an effect on the extent to which they aspire to their consonants). have also had an effect on those results. They refer to their article as a hypothesis, but strong and require additional studies.

Take him home? Whatever language we speak, dressing in a mask is a practical way to alleviate this problem. When we communicate with the mask, we keep the drops for ourselves.

Full policy and updates on the coronavirus

How to break? We act well under pressure.

I teach other people how to use their own biology to do their best.

How to break? We act well under pressure.

I teach other people how to use their own biology to do their best. After years of study, I created a 3-step approach based on neuroscience and psychology, and talked about it at TEDx. Then I went further and explored what happens when we broke the silos between the clinical disciplines. It’s amazing what you’re told when sociology talks about neuroscience, or when children’s progression talks about advertising research.

I am a board-certified pediatrician and assistant professor of pediatrics at Rush University. I have a bachelor’s degree in history from Princeton University, i. e. ideological and cultural history. My doctor is from Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine at Rutgers University. My pediatric residences. I was at Duke University and the University of Chicago. I’m a former pediatrics instructor at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine.

Me in Illinois with my husband, two turbulent children and a variety of hamsters.