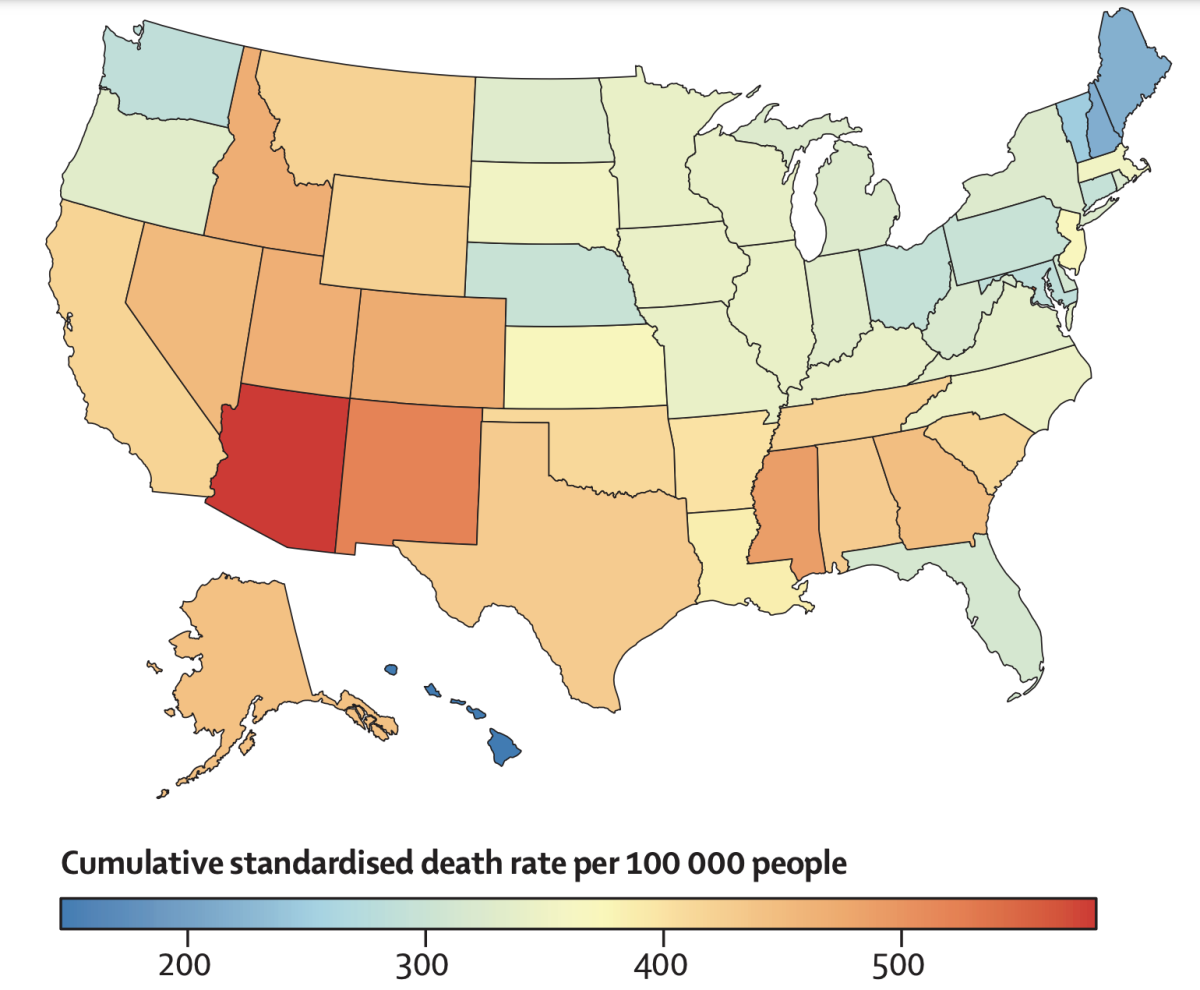

The United States has the dubious difference of suffering from the COVID-19 death rate among the world’s high-income countries. But that national average — 372 deaths compared to another 100,000 people last summer — masks the fact that pandemic outcomes differ particularly from state to state. state.

In a comparison that controlled for demographic differences between states, Arizona’s COVID-19 death rate of 581 deaths consistent with a population of 100,000 nearly 4 times that of Hawaii, where there were 147 deaths consistent with 100,000 people. Death rates in the U. S. The states resembled those of countries without fitness infrastructure. The states that proved most productive had rates comparable to countries like Australia, New Zealand and South Korea, which worked fervently to keep the number of deaths from the pandemic down.

What explains these gigantic disparities? A new one gives some intriguing answers.

Race, ethnicity and socioeconomic points were the most powerful predictors of the number of COVID-19 deaths in a state, the researchers found. With the consistent percentage of citizens’ health insurance, and the decline of the adult education point, more deaths consistent with the capita.

This possibly wouldn’t really come as a surprise. But the researchers also found that the more people in a state trusted each other, the lower their collective risk of dying from COVID-19. This result underscores how the U. S. Department of Development has made us especially vulnerable to the pandemic.

“How we feel about others is important,” said political scientist Thomas J. Bollyke, one of the lead authors of the estudio. de – is a major driving force of their willingness to adopt protective behaviors. “

The report, published last week in the medical journal Lancet, draws on a wealth of U. S. information. The U. S. Department of Health and Prevention on the pandemic from January 2020 to July 2022. Bollyke called the company “the most comprehensive to date on the drivers of pandemic outcomes. “

Dozens of researchers across the country have drawn knowledge about state demographics before the pandemic, for tactics in which their behaviors and policies diverged as the pandemic progressed. To make direct comparisons between states, they created standardized measures of infection and mortality rates that represented differences in COVID-related points, such as residents’ age and underlying physical conditions.

For example, California’s unadjusted rate of 291 COVID-19 deaths consistent with 100,000 citizens was lower than that of the remaining 11 states. But once studies took into account that the state has a young population with a low prevalence of situations that make other people vulnerable to severe cases of COVID-19, the death rate rose to 418 deaths compared to another 100,000 people. Only 15 states fared worse, the study authors found.

Demographics have told a component of the story. Political decisions mattered too.

Most states followed some sort of masking and social distancing mandates at the beginning of the pandemic, however, there were large diversifications in their degree of rigor and duration. In their imposition of public fitness measures they had lower rates of coronavirus infection.

California had the propensity to hold office, while Oklahoma had the lowest. The researchers calculated that if Oklahoma had followed mask and social distancing restrictions to the same extent as California, it would have noticed 32% fewer coronavirus infections.

However, more competitive public fitness mandates have not translated into lower death rates. The authors speculate that this is maximum probably because many older and sicker people, who had the highest chance of dying if infected, took action for themselves, regardless of whether their status or not. Governments issued strict rules.

The researchers also found that the propensity to order a state had no effect on the fitness of its economy, measured through its gross domestic product. This additional economic activity came at a price: each, based on the accumulation of percentage points in a state’s employment, was linked to 143 additional deaths for 100,000 people.

Nothing was more vital than “person-days vaccinated,” a measure of how much of a state’s population was vaccinated and when. If Alabama, which scored lowest on this measure, had complied with the vaccination policy noted in Vermont, it would have noticed 30 percent fewer infections and 35 percent fewer deaths from COVID-19 during the study period, the researchers estimated.

Another notable finding: vaccination mandates for state employees, which have sparked legal challenges, “stood out” for their arrangement with a decrease in infections and fewer deaths, the authors wrote.

The study highlights the tangible history of the country’s us-versus-them mentality, which was fully exposed during debates over mask wearing in schools and vaccination mandates for government employees. We don’t accept much as true of each other, which makes us less willing to do things to protect each other.

“Interpersonal trust” has been measured since the 1950s, and the degrees of that positive feeling toward others have declined dramatically in the U. S. He has been in the U. S. since the early 1990s, said Bollyke, who directs the global fitness program at the Council on Foreign Relations. This trend has been driven by deteriorating economic situations for low-income Americans with college degrees. It is low among black Americans and among those who voted for Donald Trump in the 2020 election.

Trust in the federal government and acceptance by science have not registered as the main drivers of COVID-19 death rates. But acceptance by his fellow citizens has been overwhelming, Bollyke said.

The partnerships discovered through the obviously recommend that the strengths and weaknesses states take in a national emergency, and some of the policies they adopt to respond to a crisis, make a big difference, said Lawrence Gostin, a public aptitude law expert at Georgetown University.

“It’s a strong case for states that have taken COVID seriously, used science, and mitigated health disparities,” Gostin said. “Much of the political rhetoric, which mandates don’t deal with and fairness is critical, has simply been shown to be wrong. “

The effects of the can be used to save lives long before the next pandemic, said Dr. Steven Woolf, a researcher at Virginia Commonwealth University who tracks the prestige of Americans’ fitness.

“A lot of the same points are affecting fitness results now,” Woolf said.

Folow

Melissa Healy is a science and fitness reporter for the Los Angeles Times and writes from the Washington, D. C. area. It covers prescription drugs, obesity, nutrition and exercise, as well as neuroscience, intellectual conditioning, and human behavior. He has worked at The Times for more than 30 years and has covered national security, the environment, domestic social policy, Congress and the White House. As a baby boomer, he largely follows trends in midlife weight gain, memory loss, and red wine fitness.

Subscribe to access Site Map

Folow

MORE FROM THE TIMES