Since it expired last year, federal officials have been begging, almost begging others to receive booster doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. But more than a portion of Americans ignored the request even for a first withdrawal, not knowing if it is necessary.

Today, a group of scientists needs other people to make a more informed decision by letting them know when their own coverage is fading.

Antibody tests have been on the market since the beginning of the pandemic, but they do little more than tell other people if they’ve ever been infected with COVID-19. an accurate point or a “low”, “medium”, “high” reading, offering more actionable information.

However, as with most things to do with COVID-19, it’s complicated.

A new house verification of the paintings has been shown in an MIT study lab, but it has not yet been expanded or made undeniable enough for general use. Test corporations do not need to invest in the long and complex procedure of obtaining federal approval. it is unclear how many neutralizing antibodies a user wants to protect. And some worry that the data is misleading, encouraging other people to get vaccinated they don’t need.

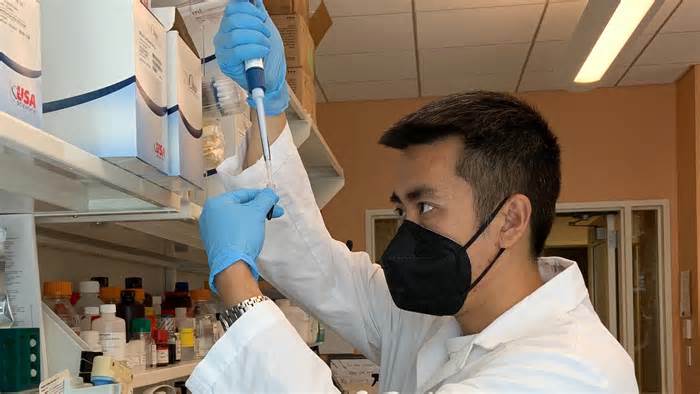

MIT researcher Hojun Li, who led the development of the new trial, sought to find out if his blood cancer patients at Boston Children’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute were vaccinated against COVID-19.

Bone marrow transplants used to treat young people with blood cancer deplete the immune system’s B cells, which are needed to fight the disease. For those young people, knowing if they can pass out in public safely can literally mean the difference between life and death. .

Li hopes his test, done perhaps once a month, can help those children and everyone else determine when it’s time for their coverage or avoid public places.

Neutralizing antibodies are to prevent a virus from entering a mobile and reproducing there. Basically, the more neutralizing antibodies there are, the more coverage there is against the infection.

While T cells from the immune formula can protect against serious diseases and last longer than neutralizing antibodies, low levels of neutralizing antibodies imply vulnerability to infections. Since existing vaccines protect well against serious diseases, but not infections, it might be helpful to know when your neutralizing antibody point drops too low to be protective.

Dr. Michael Mina, a former Harvard epidemiologist and now lead clinical director of virtual fitness company eMed, said he has been conducting antibody tests for a year to track his antibody levels and those of his circle of relatives. The booster showed that the immune formula of a member of the family circle responded adequately, but existing antibody tests can’t tell when it’s time for another booster.

Mina described Li’s new check as “a big step forward. “

Unfortunately, scientists don’t yet know how many neutralizing antibodies a user wants against COVID-19.

But figuring out the “protective correlates,” knowing how many antibodies are enough, has been tricky in the pandemic.

Li said so because it’s hard to track people’s neutralizing antibody levels over time, to see how far they had to go to be vulnerable. vaccine manufacturers.

Meanwhile, based on existing medical research, he believes that a user with antibody titers greater than 1 in 1000 (a measure of dilution of a blood pattern to lose its antibody protection) does not have to worry, while a user in the 1 to one hundred will most likely be in danger of infection and possibly receive a booster.

” d “wants to stay above 1 in 400 or 1 in 500”.

Existing tests can tell if you have neutralizing antibodies, but if you have enough to be protected.

Determining a “protective correlate” for the variant would require normal blood tests of loads of perhaps 1,000 people, checking their antibody levels and drop point before infection.

“With the burden and complexity of the existing technology, no one is excited to conduct this study,” Li said.

A house like Li’s would make this procedure much easier.

Li runs a small laboratory at MIT and produces large-scale tests.

He tested only a few times, placing his titers at 1 in 900 a few weeks after receiving his first two doses of the Pfizer vaccine, but only 1 in 20 4 months later. Since then, he has won two reminders because he can’t bring COVID-19 into his blood cancer ward at Boston Children’s.

To do more checks, try collaborating with a giant test lab. So far, people you’ve spoken to have said they’re interested, if you can get your check through the Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory process. It’s nothing of his. The team or MIT has the experience or resources to do so, Li said, so he will continue to research to find a partner.

Mina said the FDA would not authorize a control without a full clinical trial, which could charge about $50 million. “It’s just not realistic,” he said.

Instead, the FDA uses protective correlates to pass judgment on the effectiveness of a test, he said, criticizing the government for not tracking other people enough to have understood the correlates.

“We’ve spent the last two and a half years scaring the elderly,” Mina said. “The more data we can give them about what’s going on in their bodies, I think it’s valuable. “

Wenda Gao, clinical director of Antagen Pharmaceuticals, a biotech company in Canton, Massachusetts, developed a test similar to Li’s, but did not market it.

“We don’t need to pressure the general public to get spicy too often,” he said. “Possibly it wouldn’t be smart for immunity. For a healthy person, we must be very careful. “

Receiving repeated injections with the original vaccine can make it more complicated to establish an immune reaction to a variant, he said.

The average user may also not need more than 3 injections, he said, because T cells already offer coverage against serious diseases. (So far, the fourth injections have been approved for other people over 50 and others with immunocompromised diseases or medications. )

And it can be a waste for other immunocompromised people to get more shots, Gao said, because they don’t get any benefit from them.

Instead, his company is now focused on developing vaccines that offer broader protection.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday. com.

The health and patient protection policy at USA TODAY is made possible in part through a Masimo Foundation grant for ethics, innovation, and competence in health care. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.