Apple-based touch tracking apps and Google’s built-in exposure notification framework, yet have succeeded in the United States. Virginia was the first, along with Covidwise, followed by Alabama, Arizona, North Dakota and Wyoming, who introduced their own variants. The most recent reports recommend that perhaps 20 states will introduce similar applications, capable of success in a portion of the population. But they would possibly not succeed in part of the population, anywhere else. There is a fatal flaw with those touch tracking apps, as the United States is about to discover.

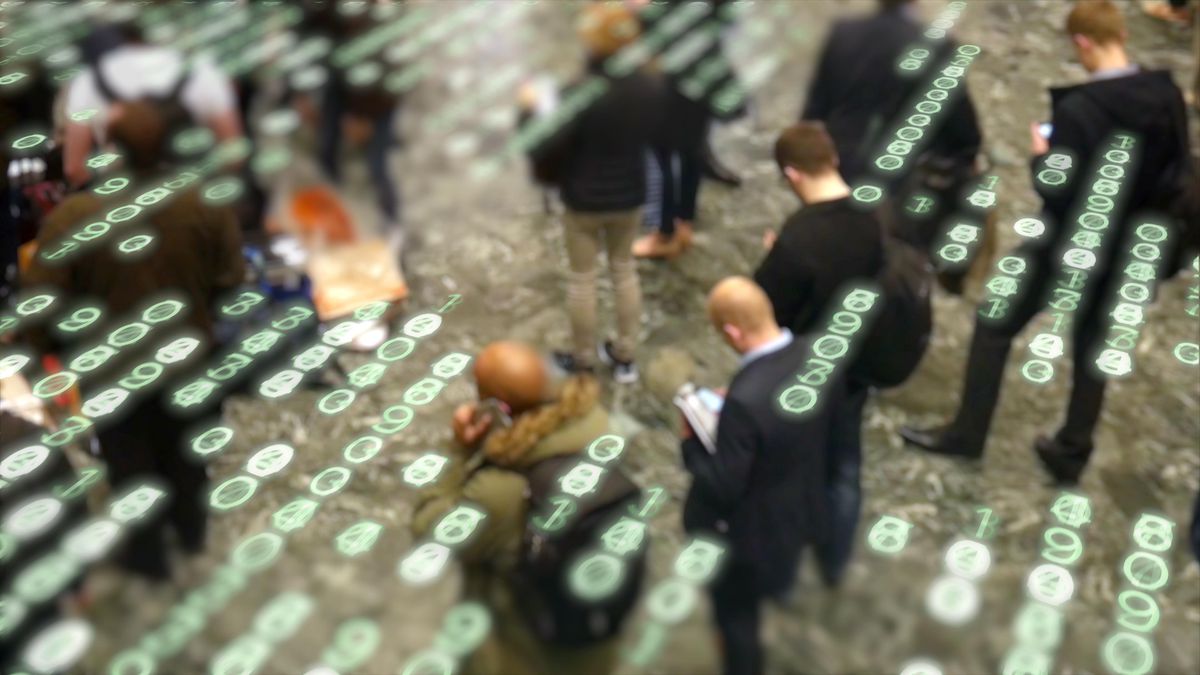

Such Bluetooth tracking programs, which necessarily fit and tag other phones with the app nearby, in case a user tested positive for COVID-19, originated in Singapore and then took hold in Europe. Originally, the concept was that applications would capture enough knowledge to identify local infection hot spots and even contextualize contacts, sitting in an exercise queuing outside. But Apple and Google first intervened with their privacy framework to prevent governments and fitness agencies from collecting that knowledge. Supported programs can mark the anonymous identity of a nearby one over the phone, nothing else, no location or personally identifiable data captured.

As I said before, this is a major challenge that greatly diminishes the potential benefits of those programs. Yes, none of us want our governments to use these programs as a backdoor surveillance platform. But don’t we have enough evidence that our phones don’t want a new contract tracking app to betray our movements and behaviors anyway? Shouldn’t we give fitness experts what they say they want?

In any case, you can set that argument aside. That’s not the critical factor here. The explanation for why these programs fail is that we are not willing enough to install and use them. And that doesn’t just mean downloading an app. This means keeping the application on and running, perhaps for several months, and then following each of its commands to isolate or test. Except you may not get many such commands, because few other people use the apps. You can see the problem. That’s pretty fundamental.

The other challenge of prohibiting the coupling or collection of personalized knowledge is that the aptitude government cannot impose, enforce, or even control isolation or testing. You cannot associate apps with the right to paint or access entertainment venues. This would be dystopian, yes, but also a very effective option for larger locks or locks. Isn’t it better to sacrifice certain individual freedoms on our phones, which already haunt us extensively, rather than economically harmful choices? Fast-forward for six months, and on the occasion of a momentary wave of widespread expansion and a backlash from other people who want to paint for a living, this debate will return.

As the programs began to gain importance, I pointed out that knowledge scientists think that about 60% of the population would want to install and use such programs to be effective. This equates to 75% of smartphone users in peak locations. To put this in context, it is similar to the WhatsApp installation base in its most popular markets. Again, you can see the problem. That’s pretty fundamental.

In any case, it now turns out that the scenario is even worse. The most recent studies published this week suggest that “even in positive assumptions,” which are explained as 75-80% of smartphone owners installing an app and 90-100% of users adhere to the recommendation to isolate or search for evidence, there is no evidence to justify the use of automated touch search approaches without further measures of public fitness control , and it is those measures of public fitness that work.

“We can’t see this as a quick fix,” the Chief Investigator at London University School told the Financial Times, while governments warned in the early closures that “it would be the panacea that would allow us to go back to the general and forget.” Covid — and if we do it right, it would solve all our problems.

Back in Singapore, where innovators from the original COVID-19 Bluetooth app temporarily discovered that it was ineffective according to the se. The relatively friendly population has noticed mandatory records in a multitude of entertainment venues, jobs and fitness facilities, as well as physical tokens carried to their entire application. And the put that have had the utmost success in confinement have used an effective manual contact search (Korea/Taiwan) and/or much more intrusive measures (Israel/China).

In any case, everything will be irrelevant. The United States won’t see the adoption you want to automate touch search. Surveys recommend that the installation and compliance of these programs in the United States will be much smaller than is needed, probably less even than in Europe. Even in Germany, where adoption is a success, there is only 20% of the population with the application. And the less effective these programs are, the less willing the others will be to install them and get them up and running. It’s a vicious circle. We have to rethink.

For touch tracking programs to work and make a significant contribution to reducing infection rates, we want additional discussion about the balance between confidentiality and effectiveness. We have to make a decision if we are willing to impose an agreement and a club, no matter how much we hate the implications and the optics. We want to find out how to link those programs to QR codes that give you the right to travel and access places where we threaten to infect others. None of this will happen until we know what form the effect of the virus will take from here, however, you can expect this debate to warm up in the coming months if the infection patterns that are emerging lately in Europe and elsewhere follow.

I am the founder/CEO of Digital Barriers, which develops complex surveillance responses for defense, national security and combating terrorism. I write about the intersection

I am the founder/CEO of Digital Barriers, which develops complex surveillance responses for defense, national security and combating terrorism. I write about the intersection of geopolitics and cybersecurity, and analyze security and surveillance stories. Contact me at [email protected].