Although millions of Americans are still suffering the effects of a COVID-19 infection, the reasons for prolonged COVID are a mystery.

In some people, symptoms can be triggered through a persistent infection, detected through testing, but oozing somewhere deep inside the body.

Or the immune system, overworked by the infection, has not figured out how to shut down and now attacks its own frame or produces destructive inflammation in places like the center or the brain.

In others, small blood clots may be to blame. COVID-19 is known to cause giant blood clots – it’s one of the leading causes of death from infection. Some studies recommend that other people with COVID have microscopic obstructions for a long time. deprive the organs of oxygen and cause symptoms.

Debilitating fatigue and brain fog, which are among the most common court cases of other people with COVID for a long time, can be caused by any of those factors.

Knowing the cause of a person’s prolonged COVID is because it makes a huge difference in how they want to be treated.

If they have a persistent infection, strengthen their immune system, perhaps with some other injection of a COVID-19 vaccine or an antiviral remedy Paxlovid can solve their problems. But if your symptoms are caused by an overactive immune system, such remedies can simply do worse things.

While other people with COVID for a long time report feeling better after a COVID-19 booster injection, others say an injection has delayed their recovery for several months. There have been no systematic studies on booster doses for other people with COVID or in any way who belongs to which category.

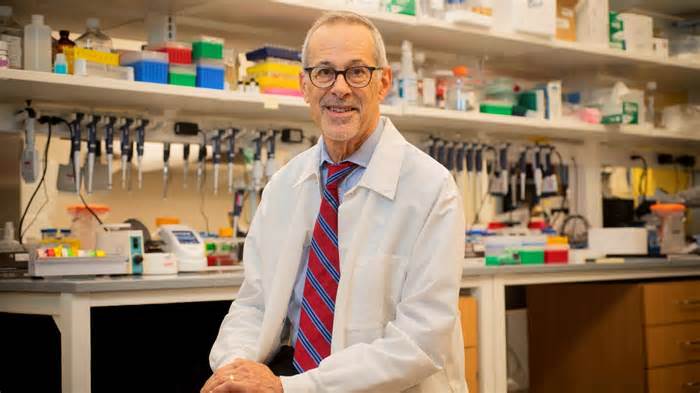

All concepts of long COVID remain “reasonable theories” and informed guesses for now, noted Dr. Eric Rubin, a microbiologist and editor of the New England Journal of Medicine.

His diary hasn’t published much about prolonged COVID yet, Rubin said, though he would like to do so. “We’re waiting for the right kind of quality data,” he said. “Anecdotes are dangerous. “

Here are some of the most common medical illnesses like prolonged COVID, their reasons, and ongoing research:

Identifying the other problems can be tricky. Many prolonged COVID symptoms are not detectable through existing laboratory tests. Objective evidence that a user has prolonged COVID would provide certainty and imply how it would be treated.

A new study provides the option of identifying significant markers in the blood to help identify at least other people with prolonged COVID, said David Putrino, article leader and director of rehabilitation technology at Mount Sinai Health System.

Putrino and his colleagues found that other people with long-term COVID were more likely to have antibodies to the Epstein-Barr virus that causes mononucleosis and the varicella zoster virus that causes chickenpox. This suggests that a COVID-19 infection could wake up those people. past infections, triggering an immune response.

“We discovered many key circulating biological points that can discriminate prolonged COVID from others,” another lead author, Akiko Iwasaki, a virologist at Yale University, wrote on Twitter.

The team also found that other people with COVID for a long time had on average much lower levels of cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone, which likely explains symptoms like excessive fatigue.

In a study published this month, researcher David Walt and colleagues found that between 60% and 65% of other people with covid for a long time had SPIKE PROTEINS OF THE SARS-CoV-2 VIRUS IN THEIR BLOODSTREAM UP TO A YEAR AFTER THE INITIAL INFECTION.

“It’s unheard of,” said Walt, a chemical biologist and professor at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The spike protein is cut through the immune formula almost immediately, Walt said. Intact spike proteins in other people with active COVID-19 infections.

Seeing so many other people with intact spike proteins in their blood suggests that the virus replicates somewhere in their bodies. the reaction can cause prolonged COVID symptoms.

These other people aren’t testing positive for COVID-19, so the virus isn’t in the lungs, Walt said, but maybe it’s hiding elsewhere, such as the gastrointestinal tract. Some other people with COVID for a long time have evidence. of the virus in your stool.

“This gives us some hope that we can expand some kind of curative intervention to that viral reservoir and give those patients the ability to recover,” Walt said.

Mitochondria feed almost each and every mobile phone in the body.

When those mitochondria malfunction, as can occur after a viral infection like COVID-19, other people can feel exhausted and depleted by energy, which is the most common and prolonged complaint against COVID.

A small Massachusetts company called Axcella Therapeutics recently finished testing an investigational drug aimed at repairing mitochondrial function in other people with COVID over the long term. Their preliminary results are encouraging.

Forty-one long-term COVID patients who complained of intense fatigue were treated for 28 days. By the end of the study, a handful of them had returned to the levels of power they had before COVID and many others said they felt better both mentally and mentally. physically.

“Seeing tiredness in such a short time, in other people who have had health problems for months, has given us hope that we can save the lives of other people with COVID for a long time,” said Dr. Brown. Margaret Koziel. , the company’s lead physician.

In some patients, one month would suffice of the drug, an amino acid combination called AXA1125, while others would likely need it longer, Koziel said, adding that the side effects were manageable.

More testing will be needed to determine the drug’s efficacy and protection before it is approved by regulators.

Some studies have focused on the option that a COVID-19 infection possibly reactivates latent infection.

More than 90% of the population has been infected with the Epstein-Barr virus, which usually causes no harm, but its reactivation may cause symptoms. A study that has not yet been peer-reviewed found evidence of Epstein-Barr activity in many long-standing COVID patients.

Another recent study found that among 88 other people with prolonged COVID, 43% had reactivated the Epstein-Barr virus, 25% had reactivated the herpes virus, and 32% had both. These infections are ideas to exaggerate the course of an initial COVID. 19 infection and accumulation of the spread COVID threat.

The cells that line the inside of blood vessels, called endothelial cells, keep blood inside the vessels. When the junctions between them loosen, blood, white blood cells and inflammatory signaling molecules can leak into the tissues and cause inflammation, Dr. Brown said. Anne Louise Oaklander, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. When there is enough fluid, the blood that is still in the vessels becomes too concentrated and clots, she says.

The blood vessels will have to open to get the blood where it is needed. If the vessels don’t open and close properly, it can cause brain fog, gastrointestinal problems, and “exercise intolerance,” the exhaustion that many other people with long-term COVID enjoy when looking to exercise or even, in severe cases, simply walk to the bathroom.

Are you or do you know affected by the long-term effects of COVID-19?Share this story.

Increased inflammation stresses the body, which leads to more inflammation, Oaklander said. Inflammation and blood clots also damage small nerve fibers, leading to symptoms of dysautonomia internally, as well as sensations such as tingling, tingling, and numbness on the outside, which are the two non-unusual long-term disorders of COVID.

Oaklander, who has been reading about nervous disorders for years, believes those disorders are not express of COVID-19, as they can occur after other viral infections.

“For 20 years, I’ve noticed that other people have symptoms similar to those of prolonged COVID,” some of which relate that to past infections, he said.

Research in South Africa and the UK suggests that in some people, COVID can leave small blood clots, affecting blood to other parts of the body.

Microcogules that block blood in the brain can lead to intellectual confusion, Putrino said.

Scientists may not be able to determine who needs treatment for microcolles until they have a test that can find it in other people with prolonged COVID, Putrino said. we can make them available to patient populations,” he said.

Dr. Michelle Monje, a neuroscientist and neuro-oncologist at Stanford University, believes that the brain fog of prolonged COVID is what cancer patients call “chemobrain,” as well as the intellectual confusion that other people complain about after the flu or with chronic fatigue syndrome.

In all of those cases, their studies suggest that immune chemicals called cytokines and immune cells in the brain called microglia are out of control, causing inflammation and restricting brain function. Different cytokines can be stimulated through other diseases: flu, chemotherapy, chronic fatigue syndrome. or COVID-19, but the end result is the same, he said.

“A lot of prolonged COVID can be explained through a dysregulated immune response,” he said.

Monje is looking to perceive the biological differences between other people who contract prolonged COVID and those who don’t, and whether the solution to reduce those rapid cytokine activities might be helpful.

Paintings can also have implications for other diseases. “Who knew that the chemobrain test would be applicable to this pandemic,” Monje said. “Who knows where COVID studies will take us. “

Many other people with COVID for a long time suffer from diarrhea, constipation, and/or abdominal pain.

Knowing what we do with the virus that causes COVID-19, it’s no surprise that it affects the gastrointestinal system, said Dr. Saurabh Mehandru, a gastroenterologist and researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

The virus is known to target a receptor in the lungs; however, that same receptor coats the small intestine, making it easier to digest certain amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

“That’s why the intestines are infected,” Mehandru said.

And there are many imaginable reasons why symptoms persist for months after the initial infection, he said. latent viruses like EBV: all this is within the realm of possibility. “

Mehandru and his colleagues began a two-year study on what differentiates long-term COVID patients with gastrointestinal disorders from other long-term COVID patients and those without.

Many other people with long-term COVID end up with cardiovascular disease, but not all of them are easily detectable with non-unusual diagnoses, said Dr. Harlan Krumholz, a cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation at Yale New Haven Hospital, which focuses on patient outcomes and selling the population’s health.

The infection itself can damage the center by causing myocarditis, inflammation of the central muscle, which can lead to shortness of breath and fatigue in the long term.

Others, who have not suffered initial central damage, may develop new cardiovascular symptoms such as palpitations, dizziness when standing, immediate heartbeat, difficulty exercising, chest pain and shortness of breath.

With all cardiovascular symptoms, “it is necessary to perform a comprehensive assessment of treatable causes, add an electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, ambulatory rhythm monitor and/or lung as tests,” Krumholz said.

Traditional cardiovascular testing may not be conclusive for other people with prolonged COVID, leaving patients unaware of the cause of their symptoms or proper treatment, he said.

“Cardiac rehabilitation can be helpful in regaining strength and maintaining power after periods of inactivity,” he said, but the remedy needs to be customized.

Two other common discomforts, dizziness and an immediate heart rate when standing up, can be caused by a condition called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or POTS.

POTS can be diagnosed with a check that leads to begging in other positions on a table while important symptoms are controlled. dressed in compression stockings. There is evidence that exercise can improve symptoms, but studies are regularly very small, he said.