In 1965, Ho Chi Minh City described U. S. President Lyndon Johnson’s half-baked billion-dollar gift to the Vietnamese, and the simultaneous risk of endless bombing, as a “rotten carrot and a damaged stick. “Achieving complete sovereignty in a unified country by defeating the world’s toughest army, an impressive task still completed in a decade (albeit in charge of two million dead compatriots and 50,000 brutal American invaders).

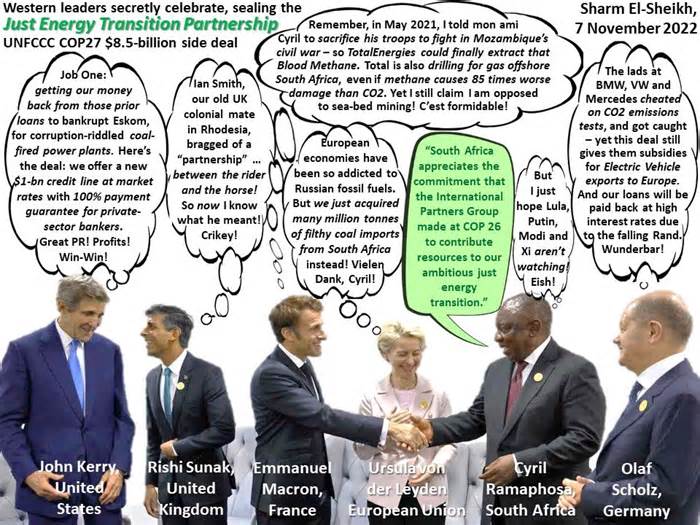

In recent weeks, Western weather policymakers have also displayed their own carrots and clubs, but unless they are withdrawn and reconsidered, they will only provide the continuation, not the brake, of a long series of emerging greenhouse fuel emissions, large losses and damage from excessive weather. and the refusal of polluters to acknowledge, let alone pay, the historic climate debt they hold. The two instances we have strongly noticed are the carrot of the Just Energy Transition Partnership and the carbon border adjustment stick. So what is rotten and what is broken?

Amsterdam Revelations

We looked at the long duration of climate injustice last Tuesday, a debate in Amsterdam at the cultural venue De Balie, with Dutch’s top climate diplomat, Jaime De Bourbon. Persuasive and charming, De Bourbon’s inability to protect the blah, blah, blah of Sharm El-Sheikh27 – the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (COP) – was nevertheless palpable: “If we go to this COP and we don’t want to, we don’t back down from the Glaspassw agreement, we have already won. I mean, which means that, therefore, the state was still quite a feat.

Is status still a feat, while the world burns, dries, melts and drowns?Indeed, the balance of forces, as evidenced through the relegitimization of Egypt’s proto-fascist host regime, justified Greta Thunberg’s refusal to attend: “Basically, COPs are used as an opportunity for leaders and other incumbents to draw attention, many other types of greenwashing. . . “And Klein warned that for blahblahblah28 in Dubai next year, “civil society deserves to announce a boycott and instead hold a genuine summit of other people. “. “

On the plus side, there is a new “Loss”

“Frans Timmermans had a lovely moment in the negotiations, where he realised we had to move forward after communicating with the EU ministers who were there. He decided, let’s move on and didn’t have time to communicate with the United States, China or anyone else. He went to the assembly and said, “Guys, we’re moving on to do it, but we have two conditions. “And along the way, when he said it, America panicked. , why are we moving forward on this, why didn’t we know?China panicked, because Frans Timmermans set two conditions.

“He said, first, to move to the most vulnerable states, so not to wealthy states that already have access to financing, such as Egypt or others. But it will have to be the states that have difficulty accessing funding and are ultra-vulnerable. .

“And second, the donor base wants to change. We in the 90s, which countries in the world at that time were evolved countries and which were emerging countries, and this, in the climate design of the United Nations, has remained exactly the same. for the past 20 years. In the meantime, do you think South Korea is now an emerging country?I would say, “By no means, it’s one of the most productive economies in the world. “

“But at the time, it was an emerging country. It is now an evolved country. I would say, in fact, the same of Saudi Arabia. Is Qatar a deficient country?There are many countries that are still classified as emerging countries, which are classified as industrialized countries, and give a contribution to climate change, and also give a contribution to efforts to find solutions.

“And the big one is the Chinese. China is lately the biggest polluter. So you think, well, traditionally they weren’t. Well, if you take a look at the old data, they are the third biggest polluter. And then let’s say, well, it’s a huge country, so consistent with capital, it’s probably not that bad. But consistent with capital, they are just above the European average. merit, so I couldn’t say that China is still an emerging country today. But it remains in the state of mind and in the organization. Therefore, they are right in the middle of the emerging countries.

And when Timmermans said that the donor base will have to be brought to all industrialized countries, he meant all that. So China got very nervous about that, however, it came, because the resolution was made. And I would say it’s progress.

We would too: not only Western societies, but also the BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa), which will be staying here next year, while Saudi Arabia, Iran, Algeria and Egypt are also applying to join “BRICS”) and some other “emerging economies” are in fact climate borrowers. And this is the case not only in terms of absolute emissions, but also whether we have the right kind for 1) trade-related “emissions outsourcing,” 2) consistent with capital responsibility, and 3) levels of old pollutants.

At times, with surprising frankness, De Bourbon commented on one of his negotiating partners in Pretoria, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe:

“The energy minister in South Africa calls himself ‘coal minister,’ just to tell you what the mindset is. Not the energy minister: “We say, no matter where it comes from, as long as you supply energy. “So it’s a very complicated thing, if you take a look at South Africa, the emissions are so big, the biggest in Africa. So he’s not a victim. That, too, is part of the problem. That’s why we want to work with South Africa That’s why finance is moving in this direction.

Oh, though, doesn’t this point contradict precedent (funding will have to “go to the most vulnerable states,” not those already with access to finance, which South Africa does through incredibly deep credit markets)?Never mind, for now, however, the dilemma of further debt financing arises, especially as Europeans have lent far more to South African borrowers in despicable fossil loans over the past twelve years.

We had this opportunity to debate basically because our allies in the task “Leaving Fossil Fuels Underground” catalyzed through the University of Amsterdam – adding the Simón Bolívar University of Quito and Acción Ecológica, a specific construction in its innovative proposal Yasuní – recognize the centrality of South Africa as the main objective of carrot and stick climate diplomacy.

Speaking of the carrot, the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), De Bourbon enthused about the option of escaping the UN’s constipated process:

“Last year we already concluded an agreement with South Africa for 8500 million dollars for the energy transition. And the same thing happened at the COP with Indonesia: 20 billion dollars for the energy transition. So you see this movement of money, and there’s a new way of working. We see that this is going to happen with India, Vietnam, Senegal. We see if we can separate that kind of thing.

Does South Africa deserve help decarbonizing the 40,000 megawatts of coal-fired power capacity of its state-owned corporate force Eskom?Already on a typical summer day, a third of this capacity is out of service due to old-age illnesses and endless accidents, leading to widespread breakdowns (i. e. several hours of “load disconnection” consistent with the day). Yes, Eskom unconsistently wants a quote for the maintenance, maintenance and commissioning of coal-fired power plants. But the parapublic app is bankrupt, unable to pay its $24 billion in debt.

In an urgent search for investment in November 2021, at the start of COP26 in Glasgow, the government of Pretoria and Eskom CEO Andre de Ruyter with partners from Paris, Berlin, London, Washington and Brussels. The latest JETP package, despite everything that was unveiled a year later in Sharm el-Sheikh, aims not only to push for the closure of coal-fired power plants, but also to subsidize the production of electric cars and green hydrogen. But we want to take a closer look at this gift.

A tasty rotten carrot for a desperate fossil addict

The central concept of the West’s JETP carrot reflects a long-standing call through the climate justice motion to leave fossil fuels in the ground in exchange for Western funding. Undoubtedly, this is obligatory for the survival of humanity. But it would really make sense if the financing were seen as a down payment on the climate debt incurred by high-emitting countries to the victims of extreme weather.

Several disagreements have emerged in the JETP negotiations since mid-2021: non-participation of communities and stakeholders; South African negotiators in bad faith, as Eskom’s decarbonisation coincided with a final quest for more fossil fuels and methane carburisation opportunities; Eskom’s propensity to redirect inbound investment to methane fuel plants; ongoing repayment of loans to Eskom that financed corrupt coal-fired power plants; and implicit endorsement of Eskom’s many egregious business practices, adding racist disconnects.

The JETP was established very sensibly, without meaningful consultation with civil society. At the same time negotiations were beginning, the South African state was encouraging two major oil corporations: London-based Shell and Paris-based TotalEnergies (and several local corporations). Small partners): to explore offshore for methane fuel in waters more than four kilometers deep. In keeping with Mantashe’s ideology, Pretoria has also encouraged ongoing coal mining and spent lots of millions of dollars on rail transport for coal exports. Plans have proliferated for liquefied grass-based fuel turbines and other fuel infrastructure.

While negotiators took their time to determine, at the latest in 2022, how $8. 5 billion would be raised and allocated as a productive maximum, the prestige quo marked the weak post-Covid recovery: reliance on coal and diesel for more than 90% of energy production; navigation based entirely on internal combustion engines; deep mining, smelting and advertising production that requires electricity; a renaissance of long-distance tourism (high emissions); fertilizer-intensive agriculture; the renovated structure of sprawling suburbs, advertising workspace, and truck-centric logistics and shipping nodes; and landfills from which unsorted biological waste releases methane.

Other major fossil fuel-focused projects continue: a $10 billion Chinese metallurgical special economic zone and, nearby, a $50 billion extension of the coal export rail line to the Richards Bay port terminal, where the main coal consumers are now European, Chinese and Indian. And large-scale methane fuel production will bring 3 Turkish Karforceships costing $12. 5 billion for a 20-year contract, a liquefied herbal fuel (LNG) terminal promoted through the World Bank, two Eskom fuel-fueled power plants costing $5 billion, and a $10 billion port petrochemical expansion in Durban.

More worryingly, more than 1,000 South African army soldiers were deployed across Pretoria in mid-2021 on the coast, in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado region, in opposition to a guerrilla army known as Al-Shabaab. Methane” through Total, ENI, ExxonMobil and China National Petroleum in a region where already one million people have been displaced by the fighting and almost five thousand have died. Massive cyclones have hit northern Mozambique, one in 2019 devastating Cabo Delgado with winds of 225 km/h.

De Ruyter is not alone, as one of the most influential corporate lobbyists, the National Entrepreneurship Initiative, supports more methane. it is transient.

But nowhere in the JETP is South Africa’s high-carb underdevelopment banned and because of the money’s “fungibility” as De Ruyter receives more than $8 billion in new investments for purported decarbonization, he can redirect revenues to his longed-for dependence on methamphetamine.

Against a rotten European carrot and dependence on methane, protests multiply

Resistance erupted in South Africa, with a progressive network, the Climate Justice Charter Movement, calling on foreign allies to initiate a boycott of the JETP. its fuel stations and other allied businesses when the JETP was announced. An exclusive mix of coastal villages, subsistence fishermen, marine conservationists, ecotourists, surfers and climate activists has kept seismic explosions at sea in the news along the shores of the Indian Ocean. and Atlantic Ocean.

Aligned with the protesters, seven times from the 2021 deadline to September 2022, public interest lawyers filed injunctions opposing Big Oil’s offshore seismic blasting, winning six of them. Business peaked when Shell and Impact Oil

Meanwhile, thanks to whistleblowers from the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party and President Cyril Ramaphosa’s leadership crusade in 2017, it is transparent that the complaint not only opposed oil companies’ demands for “economic development,” but also opposed a truly broad policy. gifts to both the ANC ($1. 1 million from Shell) and Ramaphosa ($140,000 from Copelyn). South African President.

And the financially chaotic chairman of the ANC (who, as an employer, is five years behind on paying taxes and unemployment insurance) is Mantashe. Bosasa—led to a call for prosecution through the Zondo Commission on State Capture, an official framework charged with uncovering Jacob Zuma’s 2009-2009 corruption. 18th presidency, when Mantashe was secretary general of the ANC.

Hidden Prices and Loan Terms Hurt the Economy

The JETP will also take on hard currency debt almost entirely: first, $8. 245 billion, with only 3% of the budget in the form of grants. While loans from the US ($1 billion) and the UK ($500 million) will have to be made through for-profit banks at market rates, European state credit agencies will offer “concessional” debt. the Rand/$ exchange rate was R/14. 3, but during COP27 it had fallen to R/18. 4.

Not only are fees expensive when viewed in “real real” terms (incorporating falling currency), but hard currency is not needed for many parts of the JETP (such as wages), now and especially in the future, as local production replaces imported parts of renewable energy. Eskom wants to build its own internal renewable energy capacity and power garage, and not continue to privatize electrification through outsourced contracts for solar and wind. This is expected to eliminate the 2010s reliance on multinational corporations on renewable energy that repatriated profits and dividends. to their countries of origin.

JETP finances Eskom’s methane exchange, allows corrupt loans and

On the one hand, a JETP is needed, in the form of grants, not loans, for Eskom to shift to an over-reliance on coal and ensure a genuine just transition for affected staff and communities. On the other hand, there is an immediate danger, de Ruyter has proposed a methane fuel investment program, for which he plans to use 44% of JETP’s budget, adding 1000 MW at the site of the disused Komati coal-fired power plant. On November 6, World Bank President David Malpass, whom Al Gore had told six weeks earlier deserved to resign out of embarrassment over his climate denial: He gave Eskom a $500 million loan to speed up the procedure and visited Komati.

Eskom’s other fuel plant is proposed for coal export in the city of Richards Bay, with a World Bank LNG terminal processing Mozambique’s blood methane. already in court challenging the plant.

EU cash earmarked for decarbonisation will most likely be used for methane gas, but it is also certain that Eskom’s hard currency debt will be paid off with those funds. It is almost entirely due to just two frequently failing coal-fired power plants: Medupi and Kusile (with 4800 MW each, the largest coal-fired power plants under structure anywhere), whose prime contractor, Hitachi, donated 25% of its local subsidiary ANC in 2007. As a result, in 2015, Hitachi was effectively prosecuted under the U. S. Foreign Bribery Act. The U. S. government is fined $19 million (and none to South Africa, where the Tokyo-based company has so far escaped justice).

In 2008, the scandal became public. However, Eskom’s lenders temporarily included major export-import banks in the West and the World Bank, which granted its largest loan to Medupi in 2010 ($3. 75 billion). Eskom’s new JETP debt allows it to repay previous loans, which in turn legitimizes Kusile’s Medupi Corruption. It is immoral for creditors not to take a “haircut” on those loans. JETP’s cash will not have to finance the payment of Eskom’s odious debt.

Eskom urgently wants a new renewable supply, but the “demand side” of the utility’s power grid is just as vital. The largest consumer, which employs more than 5% of the grid supply, is BHP Billiton (South32, founded in Melbourne, Australia). Its Richards Bay aluminum smelter imports the main element (bauxite) and processes it with coal power at a value of just 10% of what consumers pay. The product and profits are exported.

A similar abuse of electric power occurs at Sasol’s Secunda plant, the world’s highest point source of CO2 emissions, where an apartheid-era refinery extracts coal to produce liquid oil (which would otherwise be imported, at a much lower environmental cost). . Energizers will need to stop immediately, pushing for a just transition to be provided to affected communities and workers.

Eskom’s policies and practices want to be reviewed

It is highly unlikely to think that Eskom’s agfinisha has any kind of “Just Energy” component. Eskom remains plagued by staff corruption, by all accounts. The two most sensible CEOs of the 2010s, Brian Molefe and Matshele Koko, were arrested for billions. of dollars in corruption in October. And the disengagement policies De Ruyter imposed on black neighborhoods in mid-2020 (during the winter amid the initial shutdown of the Covid-19 pandemic), which he calls “load reduction” and critics call “energy. “racism,” they amplified through their mid-2022 proposal to end the cross-subsidy of electric power for the poor. JETP implicitly supports these retrograde policies.

Eskom has never taken the Just Transition Program seriously. In fact, forced plants and ultra-polluting coal mines now kill thousands of citizens of nearby communities each year due to particulate pollution, and De Ruyter refuses to comply with court orders to close. turbines or install emission scrubbers, resulting in what is among the world’s maximum destruction hotspots for SO2 and NO.

Other much smaller parts of JETP are also poorly designed. Subsidies for electric cars, provided by Western (especially German and Japanese) automakers, will be unaffordable for most South Africans, and there is no refueling infrastructure. But this is most likely to redirect South Africa’s long-term renewable energy capacity, for example, solar chimneys powering the national grid, at the company’s proposed export-oriented H2 production facility in Saldanha, rather than assembly. local needs.

Will climate sanctions be a painful sjambock or a damaged twig?

It turns out that South African leaders are taking only small steps toward renewable energy because of climate sanctions weighing on exporters allied with the ruling party. There is a strong possibility that sanctions will take the form of a sustained blow to the proverbial South African sjambock), however, it is clear that EU officials would prefer to use a damaged stick, or even a twig.

International industry was undoubtedly important to South African capitalism, whose industry-to-GDP ratio reached 73% in 2008, when the commodity supercycle peaked. But this ratio has declined in South Africa (to a low of 51% in 2020) and almost more so in the era of “deglobalisation” (or, as The Economist puts it, “slowdown”), with a mixture of capitalist abuse, China’s pivot towards foreign investment in infrastructure, Western protectionism (as in 2016 with Donald Trump and Brexit) and environmental lobbying that is more likely to be widely targeted climate sanctions. opposed to carbon-exporting countries.

The imposition of weather sanctions will come basically from the US, Europe and the UK, guilty of the ‘buy percent’ of South African experts. The EU will be the first, with the launch of its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on 1 January.

Even if it smells of Western imperialist power, CBAM, as an environmentally sensitive industrial policy, makes perfect sense. Without it, higher CO2 levels from dirty power countries would logically “trickle down” to the EU, as corporations outsource their production once. They face serious climate regulations and, in order to remain competitive, seek less expensive commercial inputs and unfired fabrics abroad.

South Africa and other exporting economies with very high reserves of embodied CO2 in their products, either directly or through dirty energy and shipping, deserve an incentive to transfer more temporarily to renewable sources. One way is to build EU price lists imposed on Southern African exports to Europe, and the 2020s also to other Western economies that will adopt CBAM.

The main HS exports involved will primarily be aluminium and steel, but many others (other mined and cast products, petrochemicals, automobiles and high-carbon production systems) will eventually be incorporated into the CBAM network, either because of their direct or indirect relationship. oblique emissions.

The only defensive mechanism for South Africa is to raise its own carbon tax to the point of the EU carbon market, i. e. what Eskom and Sasol (by far the two biggest polluters) are paying the Europeans: a symbolic $0. 35 per ton of CO2 emitted. For example, the price is $93/tonne in the EU Emissions Trading System carbon market and $130/tonne to cover the Swedish carbon tax.

Pretoria will not succeed at that rate, given the power relations in South Africa embodied through the hugely influential organization of energy-intensive users: 3 dozen foreign mining and smelting corporations that use more than 40% of electricity while generating less than 20% of the country’s economic output.

Joining a larger network, Business Unity South Africa, mega-energy consumers have recently argued that “South Africa’s businesses and economy cannot adapt to the scale of the carbon tax rate backlog” that is now planned: a buildup of just $30/tonne in 2030 (which is 1% of what recent estimates of the “carbon social burden” recommend).

Still, politicians and carbohydrate-rich capitalists are terrified of CBAMs. Ramaphosa revealed profound considerations about CBAMs in an October 2021 presidential bulletin: “As our trading partners pursue net-zero carbon emissions, they will most likely place import restrictions on goods produced from carbon-intensive energy. Given that much of our industry depends on coal-fired electricity, we will most likely find that the products we export to various countries face industrial barriers and, moreover, consumers in those countries would likely be less willing to buy our products.

Large corporations such as BHP Billiton (South32) and Anglo American have also started looking at renewable energy resources to avoid export taxes. China’s critique: “Unilateral measures and discriminatory practices, such as border carbon taxes, which can distort the market and deepen acceptance as true deficit among Parties should be avoided.

Source: https://static. pmg. org. za/210818_-_PC_EFF_-_NT_-_FINAL_Climate_Change_and_Carbon_Tax_Presentation_to_Parliament_NT_170821. pdf

The CBAM stick bursts

Given this fear, CBAM’s punitive sanctions will be useful for environmental justice advocates, but if defended with integrity, especially when it comes to compensating staff and communities who suffer accidental economic suffering due to companies’ inability to decarbonize.

CBAM with integrity demands at least 3 reforms. First, the most absurd recent EU climate policy has been the July 2022 resolution to label methane fuel and nuclear power as “green” in the EU’s strength “taxonomy”. This position will have to be without the delay reversed according to sound weather science, as methane is 85 times stronger than CO2 and nuclear force remains incredibly dangerous.

Secondly, the reform considers the CBAM award. Unfortunately, the point of import sanctions, starting in 2026, will be related to the bloc’s emissions trading scheme, which has suffered exceptional value volatility since 2005. In early March 2022, after Putin’s invasion, it collapsed by 40%, from about $100 to $60 per ton, and in September it collapsed from $88 to $72 per ton when Putin cut off the fuel supply. chaotic and subject to the whims of global financiers.

Third, to counter accusations of “imperialism,” Europe makes a down payment on its large climate debt by returning CBAM’s revenues to aggrieved staff and communities whose exports are taxed, in some cases until the closure of their businesses. This would be in line not only with the ethos of solidarity, but also with the ideals of a just transition.

A to refresh the carrot and harden the stick

Protests and lawsuits against the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels in South Africa will continue and are so far the most encouraging procedure in a progressive regroupment that has been hampered by divisions in the labour movement and the fragmentation of the social movement. However, this is not likely to delay stopping the array of carbon-intensive projects, given the court’s reluctance to question personal property rights and state economic policy prerogatives.

Climate justice activists want more solidarity in the face of relentless attacks on gas, oil and coal. The end of apartheid, with the close alliance of white corporations and the racist state despite everything broken. The same logic applies: with South African climate justice, the social and industrial trade union movements show dynamism and make small profits, but once again through external solidarity that decisive leaps will be made.

European elites have long blamed themselves for taking rhetorical and original leadership on the weather front, even if the effects are minimal compared to the task at hand. At least in the case of South Africa, there could be a chance in the coming months of offering a fresh, rot-free carrot and packing a larger stick, not the damaged twig on display lately.