(CNN) – The multibillion-dollar effort to discharge a marketable coronavirus vaccine can lead to delays because researchers have not recruited enough minorities to participate in clinical trials.

Of the other 350,000 people who registered online for a coronavirus clinical trial, 10% are black or Latino, according to Dr. Jim Kublin, executive director of operations for the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

This is sufficient, as the test subjects are intended to reflect the population concerned. Research shows that more than a portion of coronavirus cases in the United States involve blacks and Latinos.

Dr. Francis Collins, Director of the National Institutes of Health, gave the Modern Trial, the first of Phase 3 in the United States, a “C” for minority recruitment.

“From the first week, I saw the numbers and they weren’t as encouraging as I would have liked,” Collins told CNN.

The stakes are high. Operation Warp Speed, the government’s effort to expand a vaccine opposed to coronavirus, says it aims to deliver three hundred million doses through January, an unprecedented rate in the history of vaccine clinical trials.

If there are enough minorities registering, the expert panel that tracks the evidence can simply force a wait until they get the numbers they need.

“This is what has been actively discussed,” said Dr. Nelson Michael, Community Engagement Coordinator for Operation Warp Speed. “There’s a lot to worry about.”

Michael said several points have led to “a better typhoon of no bonté” for the recruitment of black subjects examined: ancient abuse of blacks in medical experiments like Tuskegee; They present racial injustices and disparities in health care and recent social unrest and monetary tension in the black grid due to the economic downturn.

Black leaders agree that it is a challenge to recruit blacks in vaccine trials, especially since this will have to be done very temporarily: the first two Phase 3 clinical trials began last July and full recruitment is expected in September.

“It’s a very, very complicated task,” said Dr. James Powell, a Cincinnati doctor who approached with requests to inspire blacks’ involvement in vaccine trials.

“When the other blacks listen to ‘clinical trials’, we think they’re not going to investigate us,’ and that’s based on economic prestige and education, not just one sector,” said Renee Mahaffey Harris, president of the Center. to close the fitness hole in Cincinnati.

Modern and Pfizer, the two U.S. corporations that have recently been in the Phase 3 trials, will not reveal how many of their participants belong to minority groups. Each trial will recruit 30,000 participants.

Moderna’s 89 verification sites in the United States “are actively operating within their local communities to succeed in a diverse population of volunteers,” Ray Jordan, a corporate spokesman, wrote in an email. “We hope that for an unusual purpose they examine the participants (in the COVID-19 vaccine) they will be representative of the communities with the greatest threat of COVID-19 and our diverse society.”

“I’m a white man”

Collins and Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, have made it clear that they are not the ones talking to minorities to increase their confidence in vaccines.

“I’m an old white man at the NIH,” Collins told USA Today in June. “Credibility won’t come from the organization of officials who hit the table and say, “This is smart for you.”

Fauci told CBS News last month that “a white guy like me in a suit like me and a tie, talking to other people who are other people you don’t identify with every day” wasn’t the most productive approach.

“It is necessary to incorporate the African-American network with other people who look, think and act as those who seek to convince,” he said.

Mahaffey Harris has been defending and with minority communities for 30 years.

On August 5, Mahaffey Harris won a call from a call asking him to recruit minorities in the Modern Vaccine trial.

She knows she didn’t give her the answer she was looking for.

At this stage, Mahaffey Harris will not recruit others for clinical trials. You probably wouldn’t even publish essay data on COVID19communityresources.com, an online page running through your group, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and other organizations.

“I am careful when I am contacted through someone interested in pharmaceutical studies because, as a black woman, I never need to participate in the hiring and recruitment of other people for studies that end up having prejudices or symptoms of irregularity, such as what happened at Tuskegee.” she says.

She’s the coronavirus researcher she’d meet with at the end of this month.

She has won those calls in the afterlife for clinical trials.

“They’ll say, ‘I want a hundred people,’ and I say, ‘I’m not going to attract a hundred people,'” he said.

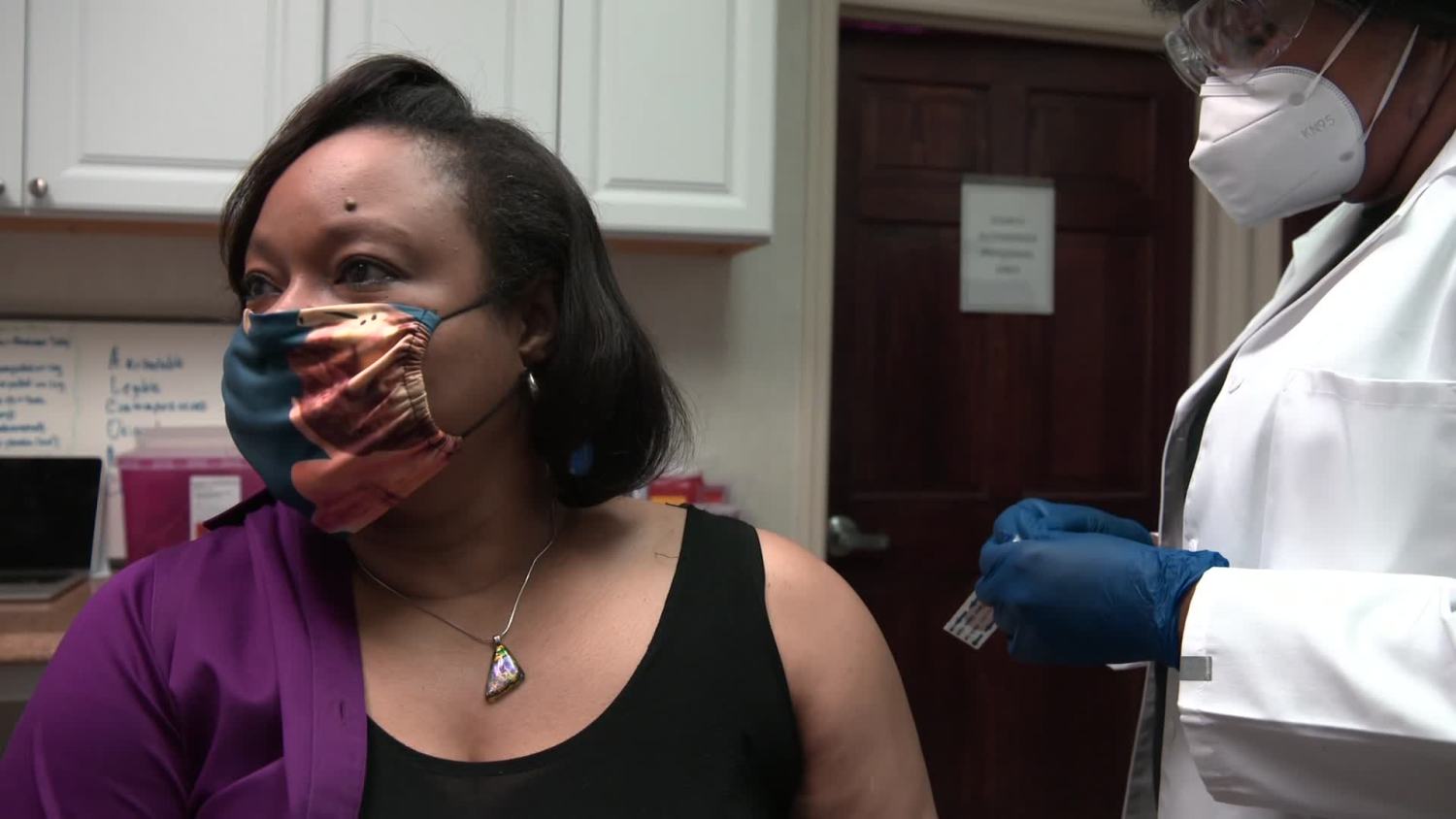

None of this surprises Dawn Baker, the first U.S. user to get a coronavirus vaccine in a phase 3 trial.

After getting her first photo, Black TV news anchor Baker in Savannah, Georgia, earned a lot of love and from her community, but also disbelief.

“Dawn has lost her mind,” one wrote on Facebook.

“I have two words…” TUSKEGEE EXPERIMENT, ” wrote another, referring to the notorious studies that abused black men.

Two other people just posted black GIFs denying with their head “no.

Baker won her vaccine three weeks ago, but said worried blacks kept coming to her to ask if she felt well.

“I told them I never felt better,” said Baker, who doesn’t know if he won the vaccine or the placebo. “But I can say they’re not sure about me.”

Government efforts to engage minorities

The NIH says it has “participation efforts” with groups, such as those representing black churches and black doctors and nurses. Operation Warp Speed, a component of the U.S. Health and Human Services Decomposer, says it has also committed to minority organizations.

Collins noted that some of Moderna’s sites are advertising and others are components of the NIH network. He said that when the trial began on July 27, advertising sites first and NIH sites opened more recently.

“NiH-funded sites are in a better position to be able to concentrate and make network commitments, to verify success in minority communities,” he said. “Look at this area, I think we’ll see it pretty quickly,” he said.

He added that he had had a meeting with Modern’s top executives on July 10.

“I heard they were committed to this kind of diversity on the record,” Collins said. “I have heard strong support from Stéphane Bancel, the CEO, and Stephen Hoge, the president. I wasn’t afraid they’d see it as smart, they were obviously very engaged.

The NIH has established the COVID-19 prevention network to recruit trial participants. In the next week at 10 days, the network will publish documents, such as print and radio ads and videos for social media, express groups, adding minorities, according to Kublin, executive director of operations of the network.

“I wish it had been a month later,” Kublin said. “We’ve all worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week to make this happen as temporarily as possible.”

Michele Andrasik, the network’s director of community engagement, said she identified the barrier to minority recruitment for trials, but is confident that progress can be made as her organization works on extension systems in partnership with network organizations.

“There are tactics to deal with the demanding situations that are inherent in the speed of what we have been asked to do,” Andrasik said.

Modern and Pfizer began their Phase 3 testing on July 27 and plan to sign them in full in September. This is an unprecedented rate in the history of clinical trials of vaccines.

But the black leaders interviewed for this tale said that mistrust in medical facilities and the government, founded on centuries of abuse and injustice, will be defeated so quickly.

“This doesn’t work at full speed,” said Dr. James Powell, lead researcher on the IMPACT project, or Increase Minority Participation and Clinical Trial Awareness, a component of the National Medical Association, which represents African-American physicians and their patients.

“They may not get the numbers next month they want. We want to build that trust,” said Dr. Doris Browne, president of the NMA.

This mistrust is not only due to Tuskegee’s experience, where from 1932 to 1972, black men underwent a syphilis test without their wisdom or consent and were not presented with penicillin to treat their illness.

It is also the legacy of Dr. J. Marion Sims, the father of fashion gynecology, who in the mid-19th century experimented with slaves in the South, performing surgeries without their consent and without the use of anesthesia before surgery.

And from the 1940s to the 1970s, in several studies, researchers exposed many subjects examined, usually black, to life-threatening amounts of radiation, according to Harriet Washington, from “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Experimentation from Colonial Times to the present.”

Injustices and disparities persist to this day.

“African-Americans are treated differently. They have less access to doctors. When they describe their symptoms, they are not believed as targets. They are denied the medical generation. All those things are recorded,” said Washington, a senior bioethics lecturer at Columbia University.

“Now we handle them with an experimental vaccine that we offer as a credit, but asking others to accept as true is to ask a lot,” he added. “There is a threat of taking an experimental vaccine. There’s just no way to cover that.”

Phase 1 and 2 trials of experimental coronavirus vaccines, with dozens or piles of subjects each, have shown that the vaccine is safe. Although some participants experienced symptoms such as fever and muscle aches, they felt more severe after a day or two.

The black leaders interviewed for this story said that, as a component of the challenge, they had been contacted through vaccine researchers a few days or weeks ago, which did not give them much time.

John Daniels is a lawyer who advises a COVID-19 advisory organization for the Church of God in Christ, the largest Pentecostal denomination in the United States with millions of adherents, usually African-American. He said he won a call by applying just two weeks ago.

“This has to be verified through a process,” he said. “In the Church of God in Christ, we have an advisory fitness organization that reaches a dozen national experts and it takes time to pass through it and translate it into the 1500 ministers and say what we’re going to do for six to eight. Millions of other people who are in our church.

Daniels and other leaders why they had been contacted so recently when it was known for many months that minorities would be needed at trial.

“The researchers knew where they were supposed to be. Why have you waited so far? Powell said about the IMPACT project.

The key to researchers getting what they want, he and others have said is to invest in long-term relationships with the black community, just call at the start of a trial and ask blacks to roll up their sleeves and get the injections on.

“Distrust is provided when reliability is not invested,” he said.

Browne, president of the NMA, said vaccine researchers have worried black doctors from the start, as part of planing and testing.

“We’re not going to make contributions at the last minute to be used as access to engage African Americans or other people of color in a program where we don’t have a transparent understanding of each and every phase,” he said. .

Dr. Paul Bradley knew beforehand that his workplace in Savannah would be the first site in the United States to inject into a phase 3 coronavirus clinical trial.

I knew that the first user I had injected would attract media attention. I came to mind the idea of who that user was and Dawn Baker’s call without delay.

Bradley has been the doctor in Baker’s Family Circle for more than 30 years. He knows Baker is loved and has enormous credibility in Savannah. In addition, she knew that as a local television presenter, she would handle the interviews perfectly.

And yes, she’s black, it’s an advantage,” he said. I knew it would motivate other blacks, and also whites, to participate in the trial.

She asked if she was interested and she said yes.

“We have developed a fair report. I move on to events, and he’s here. I met his family. It’s not just a medical relationship. In fact, I accept as true with him,” Baker said. “I knew Dr. Bradley wouldn’t do anything to hurt me.”

The next day, many other people who came to Bradley’s to volunteer, whether in black or white, cited Baker as a reason.

Baker said he knew his network was reluctant to participate in clinical trials and hopes to have made a difference.

“Maybe, since at least I’m ambitious enough to get ahead now, it might just replace that, it may eventually save your lives,” he said. “I hope just seeing my face will help them change their minds about it.”

Bradley’s links to the network have also helped in some way.

He’s known Savannah’s mayor, Van Johnson, for years, and the two discussed the trials. After the discussion, the mayor posted an article about the lawsuits on his Facebook page. Recently, on his live Facebook screen “Friday Fun”, one of his visitors was Dr. Carlos del Río, who directs the Modern essay at Emory University in Atlanta.

“I don’t take this lightly, to tell the fact and tell other people to check and be part of something,” the mayor said. “If it weren’t for the other people who defended the polio trials, we’d still have polio.”

Bradley then spoke to Ricky Temple, pastor of Overcoming through Faith, one of Savannah’s 3,000-member churches.

Ask any vaccine researcher about recruiting black participants in trials, and they will mention the strength of churches. His hope is that in a Sunday sermon, a preacher will inspire his flock to register.

Before talking to Bradley, CNN asked Temple if he was making plans to communicate about the occasions from his Sunday chair.

Temple laughs.

“You can’t just ask a preacher to say, “In our ads today, trials are going to take place and they’re looking for black people,” Temple said. “The audience is going to be — ” What are they going to come and put me a germ? “They’re going to die of worry — ” are you going to put the coronavirus on me? “”

After talking to Bradley, Temple interviewed his relatives at church and asked if he provided clinical trials at a Sunday service.

“I met my staff and no one supported me. It was 100 percent no, because of Tuskegee. I asked the members, asked the families and they gave me the same answer. It’s incredibly consistent. What I heard is fear,” Temple said. .

Temple’s decision: create a “brave conversation” about trials with church leaders.

“We are wonderful readers in our church and I will send you documents. We have a lot of fitness professionals in our congregation, I’ll bring them in combination and talk about them,” he said.

He wondered why he had to gather documents that could deal with clinical trial considerations. If the U.S. government He’s so willing for minorities to sign up for trials, why hasn’t anyone created a website, not even a brochure, with information?

Temple said one of the first things he will distribute to his church leaders is data on how, in 1997, then-president Bill Clinton apologized for Tuskegee’s study, stating that men “had been deceived through his administration.” , “they revel in a “scandal” and “deeply, deeply, morally wrong.” Clinton said she regretted “that these excuses took so long to arrive.”

Temple believes he can make a difference in the eyes of his followers.

“I’m going to create those brave conversations, because it’s anything we pray for, anything we’re involved in,” he said. “I think it can be an attractive education you can have if you open your center.”