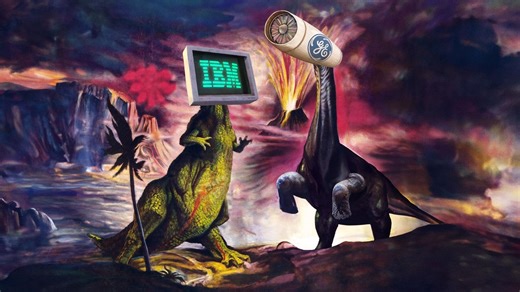

While all eyes are on megatech stocks Magnificent Seven, GE and IBM — once the bluest of blue chips — are sneaking back onto the charts, shaking off a decade of rust.

In the early 2000s, GE and IBM still held the most sensible spots in Forbes’ ranking of the largest corporations on the planet. General Electric, an original member of the Dow Jones in 1896, was a highly diversified conglomerate that grew on the dot-com craze, gobbling up corporations ranging from NBC to Kidder Peabody. By the time its iconic CEO, Jack Welch, retired in 2001, its market capitalization had reached more than $600 billion. International Business Machines, which entered the index late in 1932, was the highest-value U. S. company for much of the 1970s and 1980s. During the 1970s and 1980s, its market capitalization ranged from $22. 35 billion in September 1974 to $105. 9 billion in August 1987, two months before the Black Monday stock market crash.

But those giants of the 20th century have struggled in the new millennium. GE Capital, General Electric’s huge and heavily indebted company, which added a gigantic portfolio of subprime loans, fell to its knees during the currency crisis and was eventually dismantled and sold. In addition, a new generation of generation corporations has surpassed those safe bets in a multitude of markets, adding cloud computing.

Now, more than two decades after their peak years, GE and IBM are crafting their own comeback story. Kicked out of the Dow Jones in 2018 after a 111-year marathon, GE is flirting with its highest inventory value since the currency crisis, eager to put a seven-year crisis behind it. IBM is following a trajectory, reaching a peak in the inventory market that it last experienced more than a decade ago. In the complicated era of 2016 to 2018, GE’s inventories plummeted 75%, and IBM isn’t faring very well. better, down 32%, while the Dow Jones is up 18%. Fast forward and things have reversed: GE’s cost has tripled since 2018 and IBM’s is up 82%, outpacing the Dow Jones’ 67% increase.

Are those two dinosaurs of the Dow Jones experiencing a short-lived resurgence or are they starting a slow ascent to notoriety?

Rising inventory costs for GE and IBM aren’t as straightforward as their financials suggest. Of course, more powerful effects paint a fair picture and can soften the rise of your actions. However, the truth is more nuanced. GE, for example, reported a loss of $799 million in 2022 but rebounded to a $10. 2 billion profit in 2023, much of which came from the $5. 6 billion that came from the spin-off of its healthcare unit. a $5. 9 billion hit in 2022 to sell $16 billion in pension liabilities to Met Life and Prudential. However, as of 2023, its earnings had grown by approximately $2 billion on a GAAP basis.

Chilton Investment Company, a Stamford, Connecticut-based multi-strategy investment firm with more than $1 billion in assets under management, invested about $50 million in IBM in the second quarter of 2023, when the stock was trading around $130, according to a regulatory filing. They have become buyers in every quarter of the next few quarters. Since its initial purchase, IBM’s stock has risen 50%.

Jennifer Foster, Chilton’s co-chief investment officer since 2016, noted that longstanding skepticism about IBM’s ability to revive earnings expansion has kept many other investors away. Between 2011 and 2020, the company’s annual profits halved, from $107 billion to $55 billion, due to its inability to claim its rights, the cloud gold rush that replaced the fortunes of Amazon, Alphabet and Microsoft. IBM’s share of the market for hosting facilities and knowledge processing has plummeted. From 11% of the market in 2019, nearly double that of its closest competitor at the time, Salesforce, the company has fallen to 6. 9% in 2023. That’s still smart for the more sensible place, but it leaves it slightly ahead of Amazon, for now, according to data from IBISWorld.

As its market dominance began to wane, morale at IBM’s headquarters in Armonk, New York, also began to decline. The company’s score on Glassdoor, the site that allows workers to rate their employer, was 3. 6 out of five at the end of 2018. Today, it sits at 4. 1, ahead of tech heavyweights like Meta and Oracle, and tied with Salesforce. This update is visual even for foreigners. Foster’s interest in IBM’s inventory was piqued after a friend shared his insights while attending the company’s Think 2023 convention in Orlando.

“We cared about the stock because a smart friend who is a wonderful tech investor was at the IBM Think convention last year,” Foster says. “His comment after he left was that ‘the other people who work at IBM are just a little taller than normal. What I discovered was just an engaging comment. I followed the inventory for years and years, but we never invested in the long look because we couldn’t be sure that profits would start to grow.

Asked about Foster’s comment, James Kavanaugh, IBM’s chief monetary officer, said the more positive outlook was measurable.

“You can see a shift in overall sentiment from an investor perspective, from a visitor perspective, and in our worker engagement scores,” Kavanaugh says. “They all reflect a more positive outlook. We are fundamentally a different company and many drive around.

According to Foster, the big inflection point in profit expansion came with the $34 billion acquisition of Red Hat in 2019. Red Hat, known for its open-source cloud data governance platform, helped boost IBM’s software revenue of $18. 5 billion in 2018. to $26. 3 billion last year. But more than that, this resolution also paved the way for Arvind Krishna to become CEO.

“A lot of people, myself included, were skeptical about the Red Hat deal,” Foster says. “Did they pay too much? Was it a smart deal? But it began rather temporarily to show clever traction with IBM. And then, in 2020, the board appointed Arvind Krishna as IBM’s CEO. Arvind, the architect of the Red Hat deal, I think some of that would have possibly been lost in the Covid turmoil of the time. Arvind Krishna is a good-looking guy because he’s been at IBM for a long time, but he’s a technologist.

Krishna, who holds a Ph. D. in electrical engineering from the University of Illinois, is IBM’s senior vice president and head of research, where he led 3,000 scientists in the company’s 12 research labs. Before Krishna, most IBM executives had sales or business backgrounds, even if they were engineers. through training. Tom Watson himself has evolved in the realm of sales. John Akers, Lou Gerstner, and Sam Palmisano were all professional managers, and even Ginni Rometty, a formula engineer with a degree in computer science, got her start in the consulting industry. [Krishna] understood Red Hat’s strategy and what Red Hat could bring to IBM,” Foster says. “He brought a modern operating formula that IBM needed. Red Hat brought IBM’s relevance.

IBM’s Kavanaugh explained the deal with Red Hat as a bet that the cloud computing landscape would be drastically replaced once the initial land grab was over. IBM is betting on the long term, hoping that corporations and the market will align with the vision they considered inevitable. .

“IBM Blue and Red Hat Red were better together,” Kavanaugh says. “If you go back to mid-2018 when we announced the acquisition, we were probably only five years into the first phase of cloud expansion. The world was moving towards the public cloud. AWS, Microsoft, Google, were becoming the winners. We had another point of view. We thought of globality as multi-cloud, with corporations with multiple service providers. They would want someone like Red Hat to manage that infrastructure. If you look now, global is multicloud.

Moshe Katri, an analyst at Wedbush Securities who follows IBM, has a more reserved view on the Red Hat acquisition and IBM’s future. It maintained an unbiased score on the stock, setting a price target of $140, 25% below its current value. . Katri says that since the acquisition, Red Hat’s expansion has slowed, but noted that its contribution to earning persistent gains is pleasing to investors.

“It’s a story of hypergrowth,” Katri says. IBM remains a low- to medium-growth company.

Simply achieving a steady earnings expansion may be enough to boost IBM’s stock market momentum, especially considering the stock’s 3. 4% dividend yield. As for the company’s next catalyst, IBM CFO Kavanaugh had a quick answer: “Gen AI, Gen AI, Gen AI. The moment, however, is that we have invested and have the merit of being pioneers in quantum computing.

If IBM’s story is about addition, GE’s is about subtraction.

Larry Culp, who became GE’s first outside CEO in October 2018, methodically reversed his predecessors’ acquisitions, shrinking GE through asset sales and an ambitious plan to split the conglomerate into three separate entities. Culp’s competitive strategy aims to shape GE. Never before has it been necessary: agile and targeted management.

GE has ditched demo buys for smart sales to take on massive debt. It’s hard to compare GE’s old and new debt levels because of the large shadow cast through GE Capital (the currency unit largely dismantled around 2015), yet the numbers are staggering. Debt has dropped from a further $500 billion in 2009 (for context, that’s roughly the duration of Turkey’s existing national debt) to a manageable $23 billion today.

In the long term, GE will focus exclusively on the aerospace and defense industry. Its biopharmacy department was sold to Danaher, which CEO Larry Culp led from 2000 to 2014, for $20 billion in 2020. Its healthcare unit was spun off in 2023, while the energy segment was renamed GE Vernova is expected to hit the industry when its own inventory arrives on April 2.

According to Ken Herbert, an aerospace analyst at RBC Capital Markets, GE’s aerospace business, which will be marketed under the GE symbol, is poised to thrive. Herbert lately sees the company as a “buy” with a price target of $180.

“They’re building purely large-cap inventory in aerospace and defense at a time when there’s a shortage of quality options,” Herbert says. “The aerospace market is on fire. People are flying more while other engine brands are experiencing delays in their delivery of portions for new engines. Airlines give a genuine premium to older engines. This fits neatly with GE’s sweet spot: GE Aerospace is running at full speed while its competition is struggling.

But as GE’s stock rises, supporting Culp’s decision to break the company apart, skeptics remain.

Georges Ugeux, founder of Galileo Global Advisors, a strategy consultancy, and former managing director for Europe at the former investment bank Kidder, Peabody

“Corporate division is a surgical operation,” Ugeux says. “Surgery is expensive, it creates pain. Unless you have a very clever explanation for why to do it, you avoid it. But it’s one of the most vital games that investment bankers play. Culp listened to the bankers.

For Ugeux, GE’s recovery is a rebound after a dismal 2022, when its annual EBITDA on a GAAP basis hit its lowest point since 1985.

“The expansion of the percentage value was a general reaction to a bad 2022. It was results-oriented, but they kept the value-benefit of 20, it was just implemented in larger numbers. The question I ask myself now is: If I buy percentages of GE and I’m going to have a percentage of all those other corporations after the spin-offs and sales, will it be worth more or less than GE right now?2022 was a bad year hit hard by restructuring costs. 2023 was a year of recovery, in 2024 we will see what they can do.

RBC’s Herbert suggests that GE could soon return to making acquisitions or start backing shareholders through buybacks or dividend increases. GE will currently pay a dividend of $0. 08 per quarter, an annual yield of 0. 19%. Following the spin-off of its energy unit in April, he expects GE to now engage in strategic “capital allocation. “

“What are they going to do with all this money?” Herbert asks. We may see an era of consolidation, but Larry Culp and the control team will have arrows in their quivers. “