Commercial

Supported by

Visual surveys

A video investigation through The New York Times shows major new points about the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, a national hero who faced censorship after issuing an early warning about covid-19.

Send a story to any friend.

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift pieces to offer per month. Everyone can read what you share.

By Muyi Xiao, Isabelle Qian, Tracy Wen Liu and Chris Buckley

In early 2020, in the Chinese city of Wuhan, Dr. Li Wenliang lay in a hospital bed with a debilitating fever. He wasn’t a patient, and even then, before they called Covid, he was afraid it wasn’t a disease.

Dr. Li was widely seen in China as a hero who tells the truth. He had been punished by the government for trying to warn others about the virus and then, in a terrible twist, became seriously ill. A few weeks later, it would be the maximum death signaled from the emerging pandemic in China. He was 34 years old.

His death triggered a wave of grief and anger of a magnitude and intensity rarely noticed in China. More than two years later, Dr. Li remains a stimulating figure, a symbol of frustration with the government’s suppression of independent voices. His profile on Chinese social networks The Weibo media site gets a lot of comments a week and has become a place where other people pay tribute and share their private stories.

A government investigation into the cases surrounding Dr. Li’s death concluded in a report that Wuhan Central Hospital spared no effort to save him. But a more complete picture of his health care and treatment through the government remained elusive.

The New York Times’ visual investigations team has now filled in some of those gaps with an exclusive interview with one of Dr. Li’s colleagues. It provided a first-hand account of Dr. Li’s last hours, describing the resuscitation measures that were used and discussed. We only call him Dr. B because he fears retaliation from the Chinese government. The Times spoke to Dr. B’s video and verified his identity with public information.

The Times also received and reviewed internal memos from Wuhan Central Hospital and Dr. Li’s medical records, some of which supported Dr. B’s account. Medical records have been reviewed through experts and involve major points that fit public information. Eight U. S. U. S. China-based Chinese medical experts, who have reveled in treating covid patients or practiced in Chinese hospitals, reviewed medical records for the Times.

We found no evidence that your medical care was compromised. But those documents, along with Dr. B’s account and expert analysis, reveal vital new points about his illness and treatment.

Taken together, they show how Dr. Li spent more than 39 days facing a fatal virus and navigating the government’s attempts to censor it.

By early 2020, the virus was spreading in Wuhan, the city in China where the pandemic first took hold. Li presented to the hospital on Jan. 12 with fever, lung infection and other symptoms. According to several of the doctors who reviewed his medical records for the Times, on the third day, Dr. Li was seriously ill and needed oxygen.

“It became inflamed with an early variant of the virus, so the disease started acutely, its course was deadly and evolved very quickly,” said Dr. Wu Yuanfei, a virologist at UMass Chan School of Medicine in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Experts said that based on the records, the remedy Dr. Li received, in general, followed the criteria of the time to control the symptoms of coronavirus patients.

Just over a week after Dr. Li’s stay in the hospital, his doctors wrote that he was suffering from mental illness and diagnosed him in a depressive state, a detail that went unreported. The record did not attribute his emotional state to the expressed factors, but noted that Dr. Li had lost his appetite and may simply not be able to sleep at night.

He was kept in an isolation room, allowed to speak to his family only through a video chat. A few weeks earlier, police had sanctioned him for warning friends of a private organization on WeChat, a Chinese social networking service, about the new virus spreading in the city. His employer, Wuhan Central Hospital where he worked as an ophthalmologist, asked him to write a letter of apology, the contents of which were received through the Times.

The Times is making public for the first time the contents of the letter of apology that Dr. Li’s employer had him write.

Despite official warnings, on January 27, 2020, Dr. Li gave an unnamed interview to a primary Chinese newspaper, describing how he had been reprimanded for trying to sound the alarm. Eventually, he revealed his identity on social media and immediately became a folk hero. From his hospital bed, he took more interviews and said he hoped to join the medical staff battling the outbreak soon.

How the Times uses imagery to investigate existing events. Our visual investigation team is comprised of more than a dozen news experts who combine virtual forensics and forensics with classic reporting to deconstruct existing events. They laid out the main points about the drone strikes, police shootings and the Capitol riot.

But on February 5, Dr. Li’s condition seriously deteriorated: his pneumonia worsened, his breathing was incredibly difficult.

That afternoon, Dr. Li’s doctors ordered several tests of his lungs and heart, according to his medical records. According to Dr. Yuan Jin, a pulmonary and intensive care physician at Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton, Massachusetts, those tests recommend that Li’s medical team respond to a worsening condition.

On the morning of February 6, doctors wrote in progress notes that Dr. Li was in danger of organ failure. Several doctors we spoke to said that Dr. Li’s condition was so serious that his medical team should, at this point or sooner. , have thought about intubating him and putting him on a ventilator, a superior point of oxygen supply.

The records imply that Dr. Li had gained oxygen in the past through a nasal tube and then a supplemental oxygen mask. His medical team also tried using a noninvasive ventilator on Jan. 19, but wrote that “the patient simply cannot tolerate. “

It is not known why Dr. Li was not intubated. Some doctors are more reluctant to intubate young patients; Sometimes, patients themselves reject it. To date, there is no consensus on when invasive ventilators should be used in Covid-19 patients.

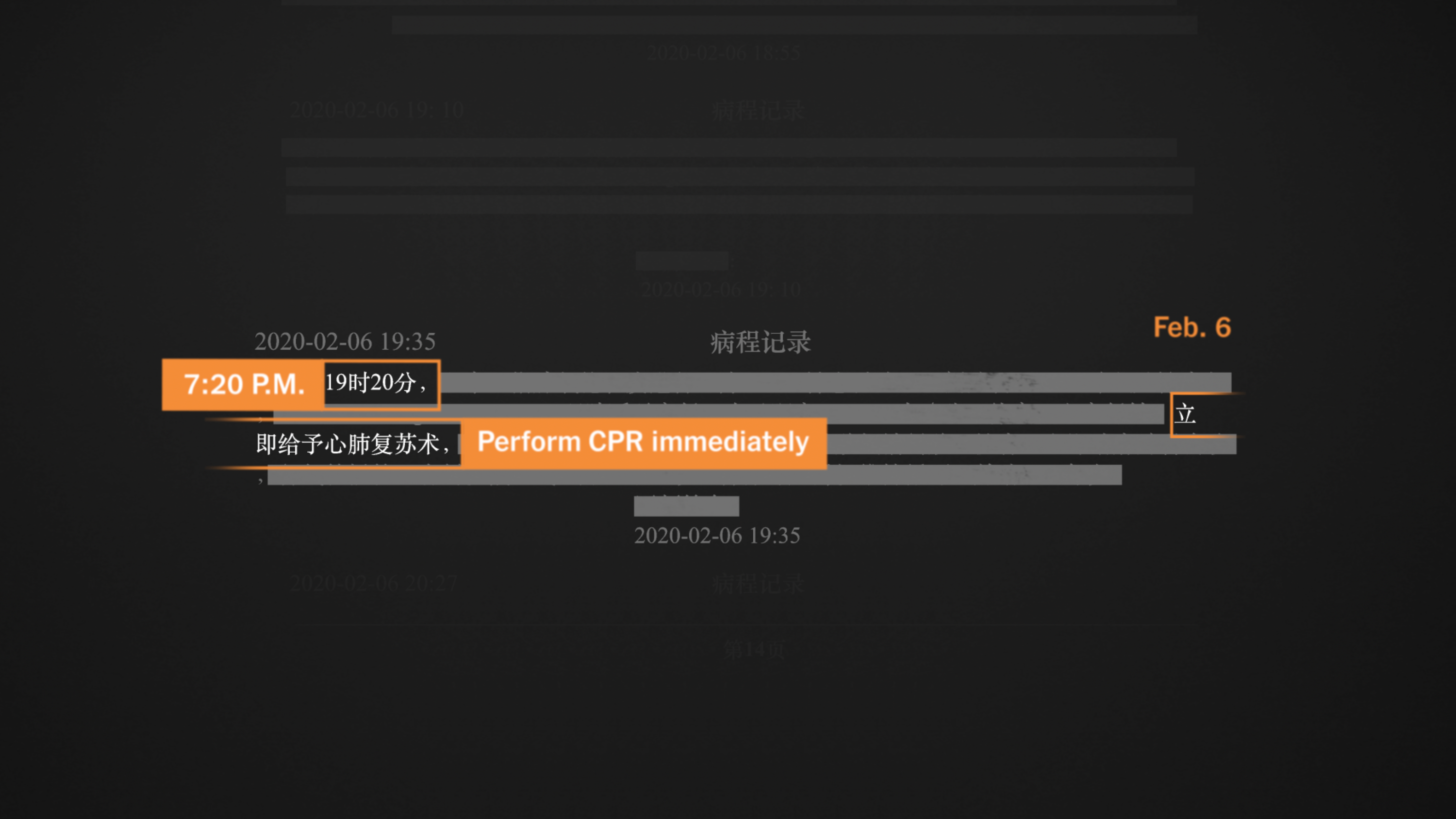

On Feb. 6, the Dra. Li went into cardiac arrest around 7:20 p. m. . He was intubated at the time, a not unusual practice of resuscitation. The note indicated that his pupils did not react to light.

According to medical records, doctors tried to revive Dr. Li for more than seven and a half hours, but his center never restarted.

The government investigation said doctors placed Dr. Li on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Also known as ECMO, it is an invasive remedy of the last hotel that involves a device that sucks the patient’s blood, passes it through an oxygenator and pumps it back into the body.

According to Dr. B, who arrived at Dr. Li’s intensive care unit around nine o’clock in the evening, about two hours after Dr. Li went into cardiac arrest, hospital control led the medical team to use ECMO because they were looking to show the public that no effort had been spared.

But several doctors in the room argued that up to that point it was too late for it to have been helpful, an assessment agreed with six doctors we spoke to. B also said that putting Dr. Li on ECMO, given its invasive nature, would have been an “insult to his body. “

Dr. B left the room around midnight. ECMO was not used because there was no tool to carry out the procedure. It’s unclear if he finally used it after his departure.

There is also no indication in doctors’ orders that night that the procedure was ever administered.

But for some reason, daily progress notes imply that ECMO was used. This is the only such anomaly discovered in medical records.

That night, the combined messages about Dr. Li’s condition, some published through state media and then deleted, generated confusion. At 10:40 p. m. , a state publication, Life Times, said he died at 9:30 p. m. m.

It was almost four o’clock in the morning the next day, February 7, when the hospital nevertheless announced Dr. Li’s death. He said he died at 2:58 a. m. a. m. La government investigation cited an electrocardiogram performed at the time that showed he was flat.

Our investigation revealed that between recordings, an echocardiogram report around 9:10 p. m. m. de the night before that it showed that his center had stopped beating.

“I think Dr. Li Wenliang was already dead when I saw him around nine o’clock on the night of February 6,” Dr. B. Il added: “The general procedure at this point would have been to declare him dead. “

“They took so long to make the announcement. It’s like the hospital doesn’t treat us like human beings,” he said. For Dr. B, making his event edition public was an attempt to share his story and honor Dr. Li’s legacy.

The Times has attempted to contact Dr. Li’s medical team, but none agreed to answer questions. The press office at Wuhan Central Hospital told the Times it is not satisfied with foreign media interviews. China’s National Supervisory Commission, the country’s most sensible disciplinary framework. Investigating Li’s death, he did not respond to requests for comment. The Chinese Embassy in Washington D. C. no responded to requests for comment.

Claire Fu contributed to the research. Elsie Chen contributed reporting from Seoul. Drew Jordan contributed to the production.

Commercial