Since her brother and wife returned after wasting her homework due to the pandemic, she has been the target of her brother’s wrath.

“My brother hit me, pulled my hair and kicked me several times. My lower stomach is now swollen and I can even see bruises near my genital area. I have trouble breathing when he hits my chest,” he told The Conversation in Indonesia. Recently.

Indah said violence had affected her psychologically.

“I cried unconsciously in my sleep. I’ve even gotten to the point where I close the door before I go to sleep because I’m afraid he’ll kill me in my sleep,” Indah said.

Indah had planned to report the case to the National Commission on Violence against Women, but her parents prevented it. They think the incident was a disgrace to the family circle and will not be revealed to the public.

Indah’s case shows how domestic violence has increased in Indonesia as a result of the pandemic.

The National Commission on Violence against Women reports that domestic violence contributed to nearly two-thirds of the 319 cases of violence reported by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data from the Indonesian Women’s Association for Justice Legal Aid Foundation also show that up to 110 domestic violence cases have been reported since the closure of March 16 to June 20. The three-month figure represents almost part of the number of domestic violence cases reported last year.

Most victims of COVID-19 domestic violence are women, reinforcing the already vulnerable position of Indonesian women.

Women’s vulnerabilities

A recent study by Flinders University in Australia highlights women’s vulnerabilities in this pandemic.

The study finds that domestic violence cases increase the pandemic because it adds to women’s diverse vulnerability bureaucracy.

These vulnerabilities exist mainly because their internal burdens accumulate as a result of the pandemic.

Women have a duty only to manage the home, but they are also assigned as teachers to their children.

Their burden increases as young people adapt to the new online learning formula: the pandemic. Women became personal guardians of their children when schools closed.

Working moms will also have to do their paintings from home. Therefore, they will have to juggle multiple responsibilities, creating an overwhelming burden.

A recent review through the National Commission on Violence against Women found that during the pandemic, Indonesian women spent more than 3 hours on family chores, 4 times more than men.

And when women don’t give birth, they’re vulnerable to violence.

Indonesia commonly accepts that women are also guilty of feeding the circle of relatives, but the pandemic has prevented women from taking on this role.

Food costs have increased as a result of the pandemic and the latest knowledge shows that Indonesians are forced to spend more cash on their families’ food.

Other than that, many of these women, usually upper-middle-class women, have lost systems to help them provide nutritious food to the family circle, such as domestic workers, in-laws, or members of the close circle of relatives, because of the confinement and social environment. Distance. Strategies.

The Indonesian Women’s Association for Justice Legal Aid Foundation said women are vulnerable to domestic violence when families revel in food shortages.

Economic hardship due to the pandemic also increases women’s vulnerability. The pandemic has caused many others to lose their jobs or reduce their wages. Reducing family incomes increases tensions among members of the family circle, with women being a simple target for abusers who justify their movements because of their monetary difficulties.

“We can see that the sick tend to come from low-income households. Pressures on fitness and the economy, with the addition of large-scale social constraints, can increase the burden on Americans and create conflicts,” karel Karsten Himawan said. , psychologist and researcher at Pelita Harapan University in Jakarta, Indonesia.

As women are more vulnerable due to increased domestic burden and economic hardship, policies to prevent the spread of COVID-19 are hampering their ability to seek help.

Although Indonesia has not implemented strict blocking policies, access to education and physical fitness is limited.

Victims of domestic violence face more difficulties during the pandemic because they are remote from resources that can simply help them, according to a report by the Pulih Foundation, a mental service for victims of domestic violence and mental trauma.

Maria Ulfah Anshor, commissioner of the National Commission on Violence against Women, said her organization’s biggest challenge is to help victims access crisis centres (refugees).

Victims must present a certificate of aptitude indicating that they tested negative for COVID-19. This procedure has proven to be a challenge for victims.

“If you stop at public hospitals or gyms to download fitness certificates, they won’t have priority because they’re not elderly and don’t have any coVID-19 symptoms,” Maria said.

How to help: Pass local and online support

Indah, in the previous story, shared her horrible pleasure on Twitter, where she knows her parents wouldn’t notice. When trying to ask for help online, you believe that Twitter is your area that provides you with intellectual support.

Through social media platforms, victims can watch videos and other content that informs others about the symptoms of domestic violence. This content helps them identify their own reports and provides them with wisdom and awareness to report their abuse.

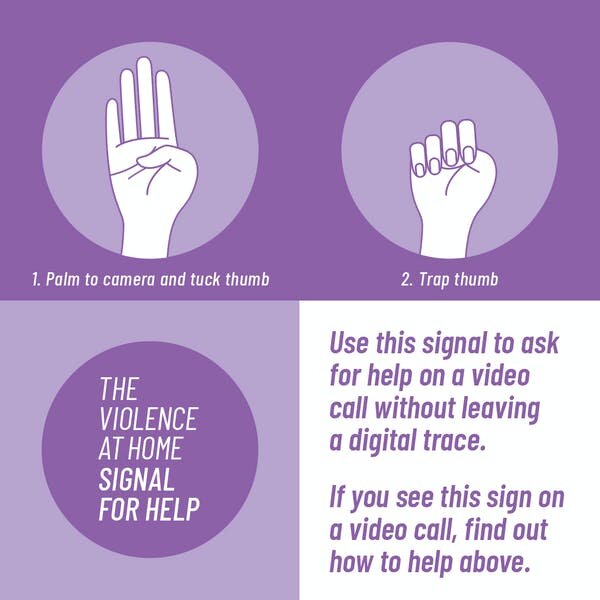

Recently, the Canadian Women’s Foundation launched Signal for Help, an undeniable one-handed signal that victims can use in a video call to silently show that they want help.

Organizations dealing with domestic violence can also be discovered on social media. Organizations such as the Pulih Foundation have a psychoeducation service in the form of articles, social media content and webinars on violence issues.

“In this pandemic, there are many hotlines for domestic violence that victims and witnesses of domestic violence can access. Contact them immediately,” said Siti Mazuma, director of the Indonesian Women’s Association for Justice Legal Aid Foundation.

Siti emphasizes the importance of strengthening the victim’s mental well-being hotlines.

The ultimate vital facet of this protection plan is the psychology of the sick. In many cases, patients need to report but are not psychologically prepared. What happens is that when their husbands cry or the police tell them to withdraw their report, those victims hesitate quietly. Siti said.

However, some believe that online connection may not be the most effective method.

Seventeen-year-old Mawar (not a genuine name) said he tried to touch a domestic violence hotline after his father hit her and her mother.

“I made several tweets about it. I even shared my non-public deal with my fans because I expected something worse to happen. I also asked them to help me with the hotline provided. I tried to call, but no one spoke returns my call, ” he said recently.

Diahhadi Setyonaluri, researcher and professor at Universitas Indonesia, recommends an approach.

Reporting and oversight at the networked paint point is mandatory if a victim does not realize that he or she is subject to domestic violence, but that the neighbor is doing so. Neighbors can help physically alienate victims from their abusers when things get worse. It’s a painting shared as a net painting to look at each other,” he says.

Indonesia is a country that emphasizes social solidarity within a community.

“This is a long-term effort because it also conforms to existing standards,” Diah said.

Strong patriarchal norms and conservative values that place men above women are dominant in Indonesia, which has the largest Muslim population in the world.

Because of these beliefs, some say it is appropriate to hit women because they intend to obey their husbands at home.