A major impediment to large-scale testing of coronavirus infection in the next world is the scarcity of key chemicals, or reagents, needed for testing, especially those used to remove genetic clothing from the virus or RNA.

A team of scientists at the University of Vermont, in partnership with a University of Washington organization, has developed a COVID-19 test approach that does not use these chemicals and yet provides an accurate result, paving the way for affordable and widely available test results in emerging and industrialized countries such as the United States. Matrix where reagent stocks are scarce.

The method, published on October 2 in PLOS Biology, omits the widely used opposite transcription chain reaction (RT-PCR) where rare reagents are needed.

92% accuracy, without the lowest viral loads

The accuracy of the new verification was evaluated through a team of researchers at the University of Washington led by Keith Jerome, director of the university’s Molecular Virology Laboratory, 215 COVID-19 samples that RT-PCR tests had tested positive, with a variety of viruses. loads and 30 that were negative.

He knew 92% of positive samples and one hundred percent negative samples.

Positive samples that the new control could not capture had very low degrees of viruses. Public fitness experts are increasingly claiming that ultra-sensitive controls that identify Americans with the smallest viral load are not mandatory to curb the spread of the disease.

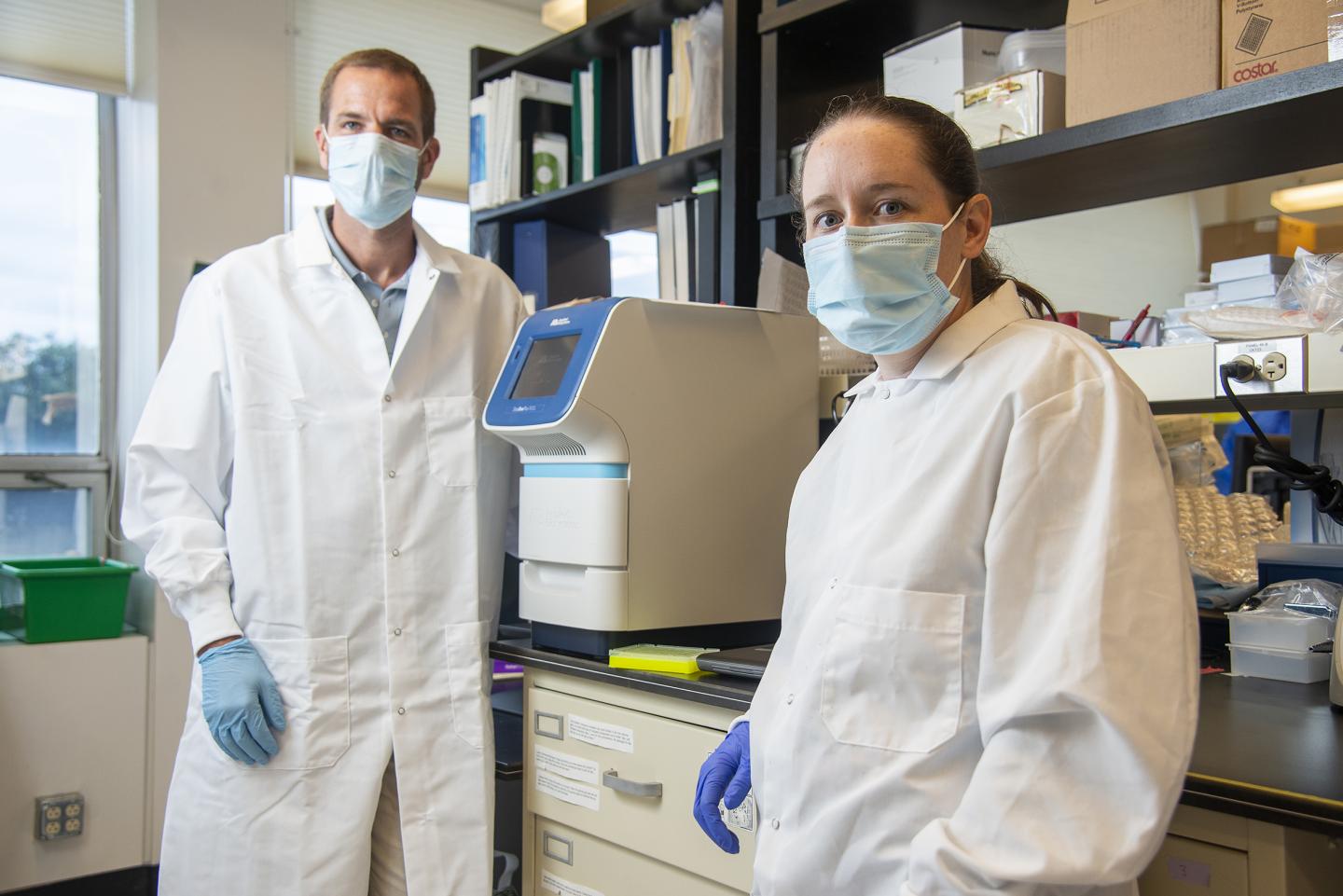

“This was a very positive result,” said Jason Botten, an expert RNA virus pathogen at the University of Vermont’s Larner School of Medicine and director of the PLOS Biology article. Botten’s colleague, Emily A. Bruce, is the first matrix of the article.

“You can go for the best control, or you can use the one that will capture the vast majority of other people and prevent transmission,” Botten said. “While the game is now aimed at locating other infectious people, there is no explanation why this check deserves not to be the center of attention, especially in emerging countries where control systems are limited due to reagent shortages. and other supplies. “

Skip a step

PCR verification has 3 steps, while this easier edition of verification has only two, Botten said.

“In step 1 of the RT-PCR test, the swab is taken with the nasal pattern, the end is cut off and placed in a vial of liquid or medium. Any viruses provided in the swab will be transferred from swab to medium,” he said. “In step 2, a small pattern of the medium containing the virus is taken and chemical reagents, which are scarce, are used to extract viral RNA. In step 3, use other chemicals to dramatically magnify any viral genetic attire that may be there. If the virus was provided, you will get a positive signal. “

The new ignores the passage of the moment.

“It takes a pattern of the medium containing the nasal swab and goes directly to the third level of amplification,” Botten said, eliminating the need for rare RNA extraction reagents and, in particular, reducing the time, labor and prices needed to extract the mid-level RNA virus at level 2.

Botten said the check adapts perfectly to screening systems in evolved and emerging countries because it is economical, requires much less time to reliably treat and reliably identifies those most likely to spread the disease.

Its low burden and effectiveness can increase the verification capacity of equipment that has not been reviewed lately, Botten said, adding asymptomatic nursing home citizens, must-have staff and schoolchildren. , such as fitness staff, where 100 percent accuracy is a must.

Influential prepress pavements for widespread adoption of the test

Two-step verification developed through the University of Vermont team first caught the eye of the clinical network in March, when the initial effects, such as the identification of six positive samples and 3 negative Vermont samples, were published as a prepress on bioRxiv. an open access repository for prepressed Biológicas. La sciences was downloaded 18,000 times (in its first week it ranked 17th among the 15 million articles published through the site) and the summary was viewed 40,000 times.

Botten heard from laboratories around the world that had noticed the prepress and sought to know more about the new test.

“They said, “I come from Nigeria or the Occidentales. No we can do tests, and people’s lives are at stake. Can they?”

Botten also listened to Syril Pettit, director of HESI, the Institute of Health and Environment Sciences, a non-profit organization that combines clinical expertise and strategies to address a variety of global fitness challenges, which had also noticed prepress.

Pettit asked Botten to join a group of experts from like-minded scientists that he organized to develop COVID-19’s global verification capability. Verification developed through organizations at the University of Vermont and the University of Washington would serve as a centerpiece. To catalyze a global response, the organization published a call to action at EMBO Molecular Medicine.

And he acted, contacting 10 laboratories in seven countries, adding Brazil, Chile, Malawi, Nigeria and Trinidad/Tobago, as well as the United States and France, to see if they would be interested in giving the check in two-stage checkup rounds. “Universally, the answer does, ” said Pettit.

Consciousness led to a new HESI program called PROPAGATE. Each of PROPAGATE’s labs will use the two steps in a series of positive and negative samples sent to them through the University of Washington to see if they can reflect the university’s results.

He’s already shown promising results. One of the laboratories in Chile also used verification in its own network samples and received accurate results.

Assuming everything goes well, Pettit and his colleagues at the University of Vermont and the University of Washington, as well as scientists from the spouses’ 10 sites, plan to publish the results.

“The purpose is to make two-step verification available to any lab in the world facing those obstacles and seeing broad adoption,” he said.