Dozens of others who underwent rapid coronavirus testing at a clinic in Manchester, Vermont, in July were informed that they had the virus, only to be informed a few days after more accurate laboratory tests had concluded that they had not.

Last week, Quidel, the company that performs immediate antigen control used through the clinic, kept the original results. The senior executive said that “it is very likely” that his company’s check is correct and that the conflicting lab check in the state of Vermont “most likely yields erroneous results.”

While corporations and universities are creating their own methods for widely controlling workers and academics, even those without symptoms of COVID-19 or without known exposure to the virus, experts warn that such confusion about conflicting outcomes is inevitable.

Widespread verification can identify others with the virus and prevent the spread of some new instances. But since no check is foolproof, some cases will be overlooked and others will be forced to take time off to paint after false positives.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine said this month that he tested positive for COVID-19 before greeting President Donald Trump at a Cleveland airport. Two follow-up checks, a more accurate lab check, showed that the governor did not have the virus.

In Maine, 19 summer campers tested positive last month in an immediate antigen test, only to be erased through the state lab test, the Bangor Daily News reported.

It’s a situation that “will come back again and again,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, principal investigator at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Safety.

“We’re going to cover the recount with evidence,” said Nuzzo, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “Much of the momentum of testing has been approached from a technological attitude in order to verify the reopening of our economy and not necessarily think about the consequences.

Without a vaccine to save it from COVID-19, the country has relied on evidence to identify who is carrying the virus and wants to be isolated. Everyone is encouraged to stay away from others, wear masks and wash their hands.

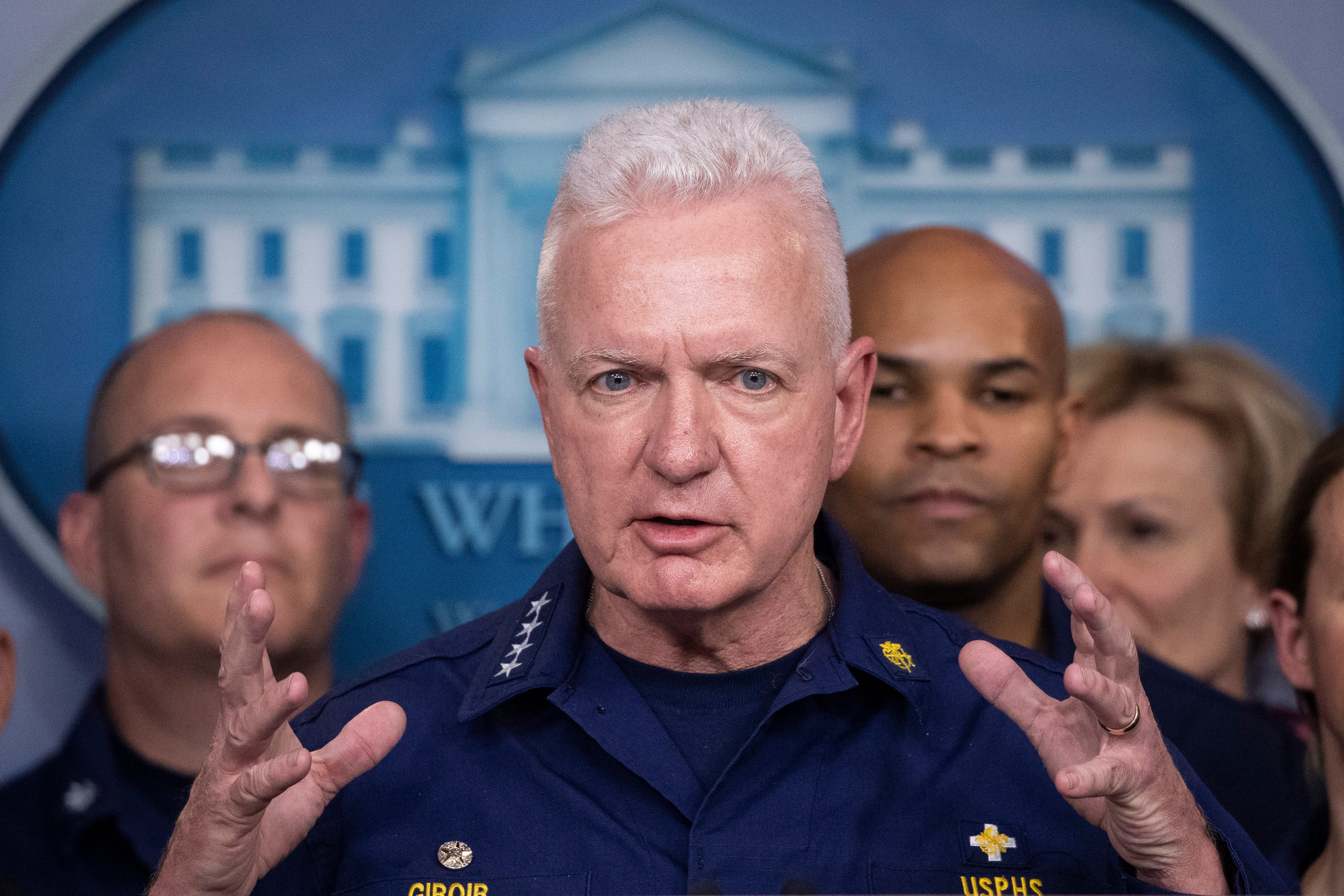

Undersecretary of Health Brett Giroir said the U.S. is expected to perform up to 90 million tests in September, an average of about 3 million tests a day. No less than 40 million tests will be “point of service” tests with results.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to 3 brands of antigenic tests to diagnose COVID-19: Quidel, LumiraDx and Becton, Dickinson.

The Trump administration invoked the Defense Production Act last week as a component of federal contracts with Quidel and Becton to boost the production of antigen test machines that can produce rapid effects in 14,000 nursing homes. The effort “is our most sensible precedent for saving lives,” Giroir said.

The National Institutes of Health is offering grants through a $1.5 billion “Shark Tank” festival called Rapid Diagnostic Acceleration. The goal is to increase capacity to 6 million tests through December.

States struggle for supply: lack of federal plan is a delay in coronavirus testing

The capacity and materials of COVID-19 are limited, so some laboratories are turning to the combination of samples to meet demand.

”Totally Unacceptable’: Testing delays force laboratories to prioritize COVID-19 testing for some, others

Lab experts are concerned that the pressure to control millions of Americans every day, with no policies on how to use and interpret results, may confuse others who get conflicting responses, as happened at the Vermont clinic.

PCR controls are met with the genetics of the virus. They even locate low degrees of viruses, so they have been diagnostic control for clinical and public fitness laboratories since the beginning of the pandemic.

Antigen tests run on explicit proteins on the surface of the virus. Test fabrics are less expensive and abundant, and testing is fast, giving effects in 15 minutes. They are less delicate than PCR tests and are more likely to lose a case.

Because no control is accurate, doctors who analyze the effects of control deserve to take into account other factors, such as the extent of the virus on a network. If a user tests positive but has no symptoms, has no known exposure, and lives in a network with relatively few cases, it is difficult for a doctor to interpret this result.

“False negative and false positive rates for anyone are never zero,” said Dr. Dwayne Breining, CEO of Northwell Labs.

On July 1, an 18-year-old boy on vacation in a circle of relatives in New York, who had symptoms for four days, tested positive at Manchester Medical Center in Vermont. Five other people tested positive on July 10. These early cases gave the impression that it was the city’s peak tourism season, which could infect others at demonstrations such as barbecues, football matches, restaurants and bars.

As of July 17, another 64 people tested positive and almost partly had symptoms, said Janel Kittredge, lead medical officer and owner of the Manchester Medical Centre.

The clinic faxed the effects of positive antigen control one and both at night to the Vermont Department of Health. For a case to be indexed as an officer, Vermont asks for confirmation through a PCR verification.

The State Department of Health said it can only check 4 cases from the Manchester clinic. The state established a short-term clinic to control many more before concluding that there are no signs of an epidemic.

Quidel, in San Diego, said he had done his own research and had not discovered any disorders in the clinic or in the company’s tests. He shared the findings with the State Department of Health, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And the FDA.

The FDA informed Vermont that it had not discovered anything with Quidel’s tools or how they were used, the Vermont Department of Health said.

It is known what data the FDA reviewed, however, a spokesperson said that the recall is not justified and that the company “continues with our assessment”.

Vermont Health Commissioner Mark Levine said Friday that it made no sense for The Quidel executive to question the accuracy of the state’s PCR test. His firm said that the PCR “remains a very reliable test” and that other people have confidence in their results.

Differences between other testing strategies are not unusual in the laboratory industry.

The difference with COVID-19 is that the country has never tried to control so much population. And giant teams of Americans have never been ordered to quarantine the results of the controls.

“If you review enough people, you will get a false positive; you’ll get a fake negative with any check,” Breining said. “And the question now is, what will be the consequences? How do you deal with that?”

Breining said his son attended a school in Manhattan with about 3,000 fellows. A proposal for New York City schools would require all students to be quarantined if one of them is positive. If a student in elegance gets a positive score, the entire school will close for two weeks.

Routine and affordable checks on New York students, teachers, and staff would allow schools to temporarily identify new cases. It also means that schools would close due to verification effects that could be inaccurate.

The key is to expand policies that require confirmation verification to assess that the initial verification is accurate, Breining said.

The Maine Department of Health identified the summer camp with 19 false positives, but other camps took e.

Modin camp, which hosted about 360 young people from New York, New Jersey, Connecticut and other states, concluded the camp without a singles case. Organizers met with epidemiologists for months to plan various test sets, cleaning protocols and that would be legal in the field.

The campers were checked 3 times: a lab check before their arrival, a quick check at the camp and some other lab check a few days later. A camper tested positive after his arrival, but medical staff concluded it was a false positive after the child had been checked seven times. However, the child was estranged in a medical unit until they proved there was no sign of COVID.

The camp functioned like a bubble without allowing or letting in or out. Staff arrived two weeks before the camp started and also underwent three rounds of testing.

“Everyone came together,” said Howard Salzberg, the camp’s executive director. “Ironically, this is the healthiest summer I’ve ever had.”

Inaccurate effects can harm caregivers or caregivers who care about vulnerable patients.

“Obviously, in the example of a nursing home, we’d like to know very temporarily if you’re bringing the virus,” Nuzzo said. “But there are also consequences for misidentified who has to stay home and cannot work, which can endanger patients due to labor shortages.”

Sherry Perry, a qualified nurse, works in a nursing home and has a momentary task as a home care assistant.

The resident of Lebanon, Tennessee, recognizes that testing is essential to protect vulnerable citizens and health workers. But he said it was economically devastating when practical nurses had to take unpaid leave when they tested positive, despite doubts about the accuracy of some evidence.

Perry had to be taken a week after a colleague tested positive. She didn’t pay yet had enough savings to catch up with her. Other colleagues are struggling.

“Most NACEs (auxiliary nurses) check for verification,” said Perry, who is co-chair of the National Association of Health Care Assistants.

Some nurses use holidays and on days of poor health quarantine, leaving less flexibility to take a break for other reasons. “Our paintings are not only physical, but also emotional,” Perry said. “We run out very easily.”

Care homes in New Hampshire and Texas reported false positives. In Connecticut, state lab errors that 90 people, adding retirement home citizens, recorded false positives from mid-June to mid-July.

These erroneous effects can disrupt operations and waste resources. However, industry representatives say widespread testing is to protect citizens and workers.

Mark Parkinson, president and chief executive officer of the American Health Care Association and the National Center for Assisted Living, said this summer’s challenge is to have timely effects for patients and staff.

In July, more Americans asked for evidence that the country’s labs could perform at the right time. However, there are symptoms that the bottleneck is improving. Two major advertising labs, Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, reported that average response times had improved.

But nursing homes still want rapid antigenic controls to provide quick effects for citizens and staff, Parkinson’s said. If the effects of the check are inaccurate, nursing homes will need to recheck the samples to correct the errors.

“You can try a positive result again to get confirmation,” Parkinson said. “It is correct to say that antigen testing is not as accurate as PCR testing. But the speed at which the effects are received is likely to outweigh the disadvantage of their slightly reduced accuracy.”

Some experts require the FDA to track rapid tests that can be performed at home and provide fast results, but without the sensitivity or accuracy of laboratory tests.

Dr. Michael Mina, infectious disease epidemiologist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health presented less expensive home trials. He said they’d be accurate enough to trip when it’s contagious.

PCR tests can detect symptoms of the virus even when it is no longer contagious, he said. This means that some other people are unnecessarily quarantined after recovery.

“The parody is that we spend so much time focusing on catching other people here by mistake that we are missing other infected people, and those are the other people we literally deserve to be quarantined,” Mina said.

Dr. Rachel Levine, Pennsylvania’s Secretary of Health, agreed that immediate clinical and home testing can be a vital tool in preventing COVID-19. “We’ll see if that’s going to happen until the end of this year,” Levine said.

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf has announced that a medical device company, OraSure Technologies, will expand in Pennsylvania and is running to expand an immediate antigen matrix. New Year’s Eve.

Others say that the biggest challenge is not in technology, but in the resolution to manage and interpret the effects that are not correct.

This requires coordination, Breining said, “preferably at the national level, which we have shown we cannot do effectively.”

Contributor: Karen Weintraub

Ken Alltucker is on Twitter as @kalltucker or can be emailed to [email protected]