BOSTON – Dianne Wilkerson black Bostonians will volunteer for trials of possible vaccines opposite COVID-19.

She understands why they hesitate. African Americans have a long history of abuse through medical facilities; many were themselves discriminated against in opposition to health care.

However, if they do not participate in vaccine efficacy and protection trials, they will never know if vaccines will work for them.

“The dangers of worrying are so great,” said Wilkerson, a founding member of the COVID-19 Black Coalition in Boston.

Approximately 25% of the city’s population is black, however, blacks account for more than 35% of the inflamed and killed by COVID-19.

Nationally, the numbers are even worse. A few more than 80 black Americans died from COVID-19 out of 100,000, to 46 Latinos and 36 white Americans, according to the American Public Media Research Lab.

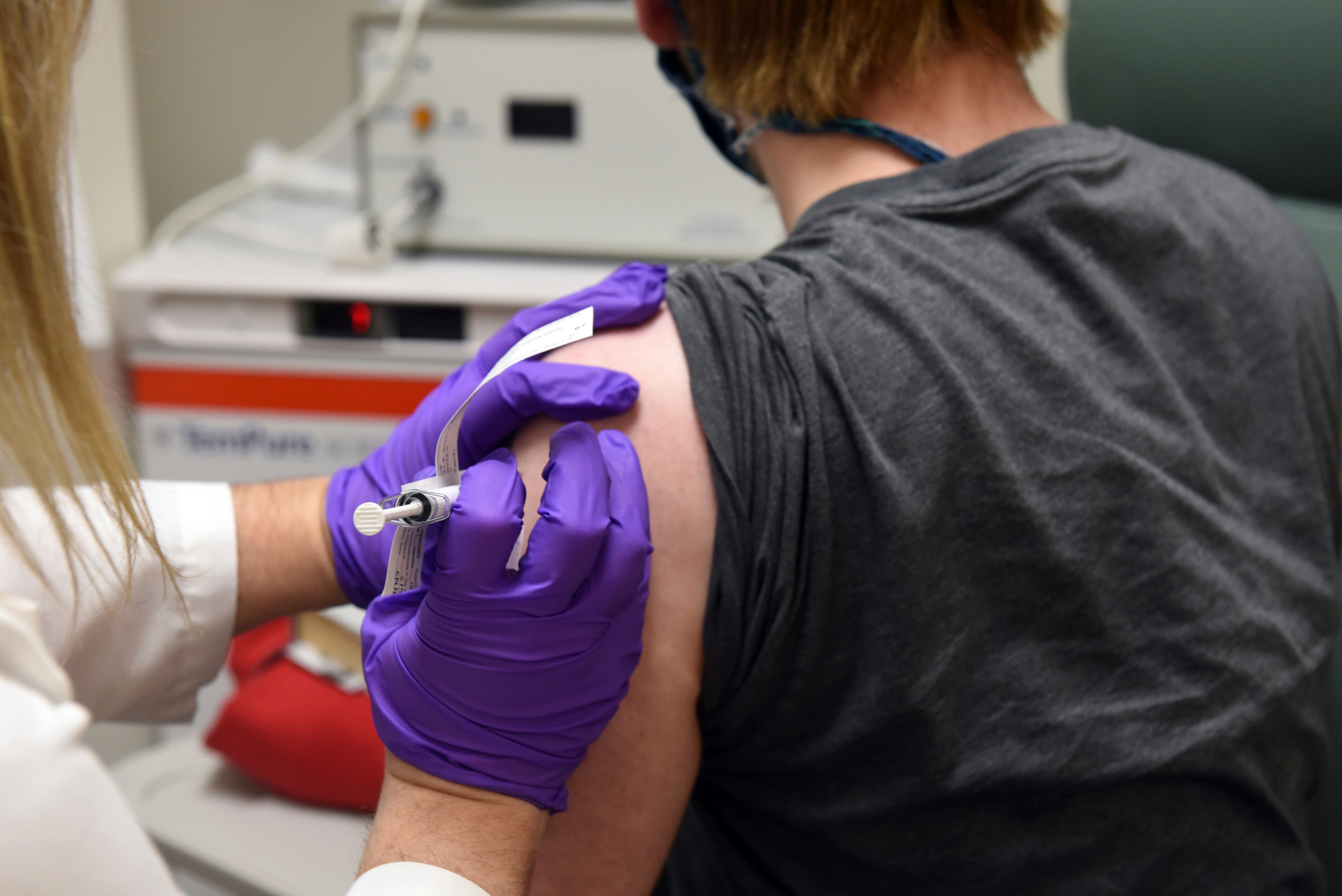

The first two large-scale vaccine trials began nationally last July, and at least 3 more began before early fall. Each will want 30,000 volunteers, some of whom will get an active vaccine and the other a placebo.

Federal officials, in addition to officials from the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have called for trials to include a large number of other people of color.

“We want to make sure there is adequate diversity in clinical trials,” said FDA commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn in a recent interview with the editor of the clinical journal JAMA.

Even if everyone’s immune formula reacts the same way to the virus, the underlying differences in attention and fitness may mean that other people of color react to the infection, Hahn said, “We want to make sure those other people participate in those trials to perceive what the immune effects are, but also the clinical effects.”

In addition to racial and ethnic diversity, maximum trials also seek out other people over the age of 65. 19.

The first trials diversified.

In the two small clinical trials that published their results, one in the New England Journal of Medicine and the other in The Lancet, only 8 of the 1,100 participants were black. In either study, the average age of participants in the mid-1930s.

It’s not for lack of enthusiasm in the trials. More than 300,000 more people have already expressed an interest in volunteering to participate.

The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, which manages a volunteer registry, does not divide them by demographic. But Hahn said 19% of those who had volunteered so far were black and almost the same percentage were Latino.

And while 300,000 are like many volunteers, that’s not enough, said Claire Hudson, the center’s spokeswoman.

“It is vital to note that we want millions of interested volunteers to sign up for the online registration,” he said via email at coronaviruspreventionnetwork.org.

Not all other people who show interest in volunteering will be part of one trial, Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said at a teleconference that delivered the beginning of the first trial. Some volunteers might not live near control sites, for example.

“The more there is, the better,” Collins said of the volunteers. “This will be a wonderful opportunity for Americans to join us as partners in seeking to participate in what has been a historic effort to end the world’s worst pandemic in over a hundred years.”

Dr. Barbara Pahud has a plan: if there aren’t enough people of color to attend primary medical centers to volunteer for clinical trials, she will take clinical trials.

As a medical student in Mexico, Pahud won a vaccine cooler to deliver to the community. He has now provided a pickup truck that he plans to park, in a fitness center or in a church, for vaccine testing where Americans of color spend their time.

Pahud, director of pediatric infectious diseases studies at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, said she also applies to rent to other Spanish-speaking people and put all the published fabrics in two languages.

“The same old things that deserve to be done are really done this time, which is fantastic,” he said.

Both researchers and members should take risks.

“If we really want to do studies that reflect the network we live in, which is affected by this disease, we (the scholars) want to replace our way of thinking,” Pahud said. On the other hand, “communities want to perceive that if they want to gain benefits from the vaccine, they have to let their other people volunteer, otherwise we would not know if the vaccine is working in their population.”

Others make efforts.

At the University of Colorado, Thomas Campbell said his medical practice had used his electronic medical records to identify and succeed in all other people who are in the greatest threat of COVID-19.

“I’ve already won over a hundred people who emailed me and said ‘register me,'” said Campbell, who is also an infectious disease doctor at UCHealth.

Pfizer, who has filed its own demand for 30,000 people, is starting its demands in communities, adding some with giant Hispanic and black populations, spokeswoman Sharon Castillo said.

“We make sure that the demographics of our checking population reflect the demographics of the states and communities that have been most affected,” he said.

Pfizer also works with partners, such as grassroots organizations and Spanish media, to raise awareness and inspire participation. And the company reduces barriers to participation, Castillo said, printing documents in five languages.

“We are learning a lot about how to move beyond expectations for minorities to be represented,” he said, and promised that Pfizer would continue this technique in all of his clinical trials in the future.

But smart intentions might not be enough.

Wilkerson said a recent meeting with Brigham and Women’s Hospital officials ended where she wanted.

The hospital contacted black leaders and added Wilkerson to inspire minority participation in those trials. Hospital officials said meetings and other meetings with other local people of color went well.

“We are committed to a substantial and engaging discussion about how we can work in partnership, either for the local implementation of this trial and for long-term clinical studies in general,” said Allison Moriarty, Brigham’s Vice President of Research and Compliance Management.

But Wilkerson said a few listening sessions and delivering flyers to local network centers would be enough to correct decades of mistrust or interact with black Bostonians.

“We have the opportunity to re-establish the way (hospitals) relate to blacks and maroons,” he said, adding that his organization plans to seize this opportunity: “We intend to get your attention.”

Contact Karen Weintraub at [email protected]

Usa TODAY’s patient protection and physical fitness policy is made imaginable in components through a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competence in the Health Sector. The Masimo Foundation does not contribute any editorial contribution.