n n n ‘. concat(e. i18n. t(“search. voice. recognition_retry”),’n

(Bloomberg) — In late 2019, the European Union announced its Green Deal with the goal of leading the world toward a sustainable future. Then came Covid, emerging inflation, supply chain disruption, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Most on Bloomberg

Texas Turnpike Buyback Will Net Taxpayers at Least $1. 7 Billion

Saudi Crown Prince MBS’s $100 billion investment search fails

Zimbabwe replaces minted currency with a new gold-backed currency called ZiG

Abandoning China is difficult, even for Argentine anarcho-capitalists

The s

All of this has pushed energy costs, protectionism and festivity onto the EU’s agenda, making the ambitious blank transition more politically and economically challenging.

So while this is a moment of progress as projects move from political documents in Brussels to truth in the houses of Lisbon and Helsinki, the profoundly replaced global media makes officials want to reconsider certain elements to keep European industry running and avoid a voter backlash. .

Consumers, still scarred by the cost-of-living crisis, are wary of anything that touches their pockets, and businesses oppose excessive regulation.

In addition, climate-sceptical far-right parties are gaining ground among the public in the run-up to June’s European elections. Already this year, some measures have been relaxed after protests by farmers, who opposed the ecological push before it was just starting to farm.

Reversing course is not an option, but it is becoming increasingly clear that Europe cannot make mistakes. A wrong reform would mean that businesses and consumers would pay a huge bill of trillions of euros for the green transition, while giving China and the US the opportunity to pay a huge bill for the green transition. a plus.

Amid those concerns, EU diplomats say trade competitiveness will most likely skyrocket up the priority list once a new European Commission takes over after the election.

The threat of the EU losing new investments in blank generation when it peaks has been compounded by the U. S. Inflation Reduction Act, which provides around $500 billion in new green spending and tax breaks over a decade.

While there is a debate on the continent that proposes the most effective path, most agree that the European framework is more complex and based on a regulatory stick rather than a carrot.

Investors want “a business case, not prescriptive regulations,” said Martin Brudermueller, chief executive of Germany’s BASF SE and chairman of the European chemical industry deal Cefic. “In Europe, regulations are complicated, time-consuming and offer no incentive to invest. “

Big ambitions

When Commission President Ursula von der Leyen unveiled her plan to make the continent climate-neutral by 2050, she saw it as a watershed moment for Europe.

The concept that the faster the EU reduced its emissions and deployed low-carbon technologies, while creating new jobs, the stronger its position in the new global economy.

The adjustments needed to achieve the competitive targets were worked out over the next few years in heated negotiations with the bloc’s member states and parliament. Dozens of measures have been adopted, ranging from a de facto ban on combustion engines in new cars until 2035 to stricter pollutant limits for corporations and a new carbon market for fuels.

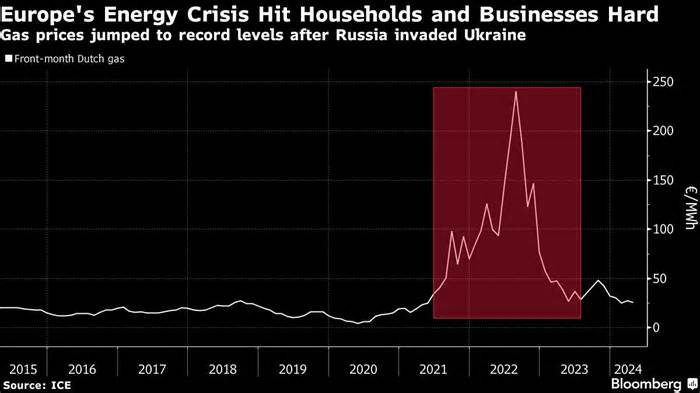

But at the time, the fallout from the pandemic disrupted global supply chains and highlighted Europe’s dependence on imports of essential raw materials. Second, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drove up energy costs, affecting an economy looking to break out of lockdown.

“If we don’t get effects at home, if we send the message that the Green Deal has caused social upheaval, it will be an example for other countries to follow,” said Simone Tagliapietra, a senior researcher at the Bruegel think tank. .

Controlling energy prices is one of the biggest challenges. Energy has been more expensive than in the United States or China, but the war has accentuated the difference, undermining competitiveness.

In the run-up to European Parliament elections across the bloc, the Commission and some member states are becoming more receptive to calls from businesses. Last month, von der Leyen joined the publication of the European Industrial Agreement, an initiative subsidized by nearly 1,000 companies, unions and associations calling for cheaper energy, less red tape and more investment in blank technologies.

“We want to reap greater and fairer benefits from the transition,” said Petros Varelidis, an adviser to Greece’s environment ministry. “Broad social acceptance is a prerequisite for a successful transition. “

Europe already has – according to its own estimates – its binding target until 2030 to reduce emissions by 55% compared to 1990 levels. But he is determined to press ahead and has floated the concept of some other intermediate target: 90% by 2040.

Most of the measures for 2030 have not yet come into force. Recent moves among farmers highlight how difficult it will be for the commission to not only move forward with new regulations, but even comply with what was agreed.

It will have to be a “just transition, with competitiveness for the other industries in our member states,” EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra told EU environment ministers last month. “One will not be done at the expense of the other. “

To counter voters, the EU has earmarked billions of euros in investments to protect the most vulnerable and inspire corporations to invest in low-carbon technologies.

However, massive personal spending will be required and policymakers are scrambling to come up with new mechanisms to attract funds. The EU estimates that to meet the 2040 target, around €1. 5 trillion ($1. 6 trillion) will be needed from 2031 onwards.

In a document published in March, the EU said the temperature in Europe would be 3 degrees Celsius warmer even if the world controlled global warming to 1. 5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, causing billions of euros in damage to the economy. “A conservative estimate” shows that climate change could increase economic output by about 7% by the end of the century.

“What we have agreed so far is ambitious,” said Jos Delbeke, a professor at the European University Institute in Florence and a former senior meteorological official at the commission. “There will be no turning back, but at the same time new regulations will also be implemented. “Let’s not make the transition harder. “

–With those of John Ainger and Gina Turner.

Most read Bloomberg Businessweek

How Hertz’s Tesla Thing Went Horribly Wrong

Elon Musk’s X Has a Problem

Repairing Boeing’s Damaged Culture Begins with New Airplane

How Bluey Became a $2 Billion Smash Hit, With an Uncertain Future

China’s Property Tycoons Lost $100 Billion in Housing Collapse

©2024 Bloomberg L. P.