SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 diseases are causing a global crisis. Governments have responded by restricting human movements, which has reduced economic activity. These adjustments would possibly gain benefits for biodiversity conservation in some respects, however, in Africa we argue that the net conservation effects of COVID-19 will be strongly negative. Below, we describe how the crisis is creating the best typhoon of reduced funding, restrictions on conservation firm operations, and major human threats to nature. We identify the quick steps needed to address those demanding situations and ongoing conservation efforts. Then we highlight systemic failures in fresh conservation and identify restructuring opportunities for greater resilience. Finally, we emphasize the critical importance of habitat conservation and the regulation of harmful practices of the wildlife industry to reduce the threat of long-term pandemics.

The world is recently facing a primary disease pandemic due to SARS-CoV-2 and its related disease, COVID-191. Governments are taking drastic steps to stop the spread of the disease, adding foreign restrictions and blocking millions of others. These measures have major socio-economic impacts, as companies and industries close or reduce their activities. Global stock markets have become volatile and a global recession is looming. Virtually all life spaces are affected and most likely to remain affected for at least 6 to 12 months2. The African economy may suffer simply from declining foreign investment, declining remittances and foreign aid, and declining overall incomes3. Gross domestic product (GDP) can contract by up to 4%, and governments face lower tax revenues and devalued currencies, resulting in severe budget deficits and domino effects on African livelihoods4. Blockade restrictions and economic unrest can also jeopardize the conservation of Africa’s wildlife and wildlife, as well as other people who benefit from them.

Africa has about 2,000 key biodiversity spaces and is home to the world’s most varied and abundant giant mammal populations.5.6 Financially, the obvious maximum price of Africa and wilderness areas comes from tourism, which generates more than $29 billion a year and employs 3.6 million people 7. Trophy hunting, a subset of the tourism industry, generates about US$217 million, consistent with the year in more than one million square kilometers (ref. 8, 9). Tourism is helping governments justify habitat coverage. It generates a source of income for national authorities, generates foreign exchange income, diversifies and strengthens local economies, and contributes to food security and poverty alleviation (Table 1). Tourism generates 40% more full-time jobs consistent with the investment unit than agriculture, has twice the strength to create jobs than the automotive, telecommunications and financial sectors, and employs proportionally more women than other sectors10.

African wildlife also attracts abundant foreign investment through the financing of conservation efforts (Table 1). Diversity of taxpayers from multilateral establishments and bilateral investment agencies to personal foundations, philanthropists, zoos and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Reliable knowledge of the scope and composition of donor investment is scarce, but external knowledge represents a really large proportion of total investment for wildlife conservation (Table 1). For example, donor contributions account for 32% of investment in protected domains (APs) in Africa, reaching 70-90% in some countries11.

Wild areas and conservation spaces provide essential resources for other locals who gain benefits from the use of wildlife, grass, water, firewood and non-wood forest products. In times of misery, such as economic recessions, others are more dependent on these resources.12 In addition, African wildlife provides vital cultural and heritage prices to ethnic groups, and charismatic species have an abundant symbolic price at the foreign level.13 African wildlife also has an abundant price of “existence,” the price other people get for the simple fact that it exists.14

The backbone of African conservation efforts is 7,800 terrestrial APs covering 5.3 million km2, or approximately 17% of the continent’s land domain15. The AP canopy in some countries (particularly in southern and eastern Africa) far exceeds the global average. In some parts of Africa, vast cross-border conservation spaces go beyond national borders, creating protected landscapes spanning thousands of square kilometers. Most APs are state-owned and controlled through government wildlife authorities, with really extensive help from tour and hunting operators16. Conservation NGOs and personal sector entities are increasingly cooperating with governments to manage state-owned APs through Collaborative Management Associations (PMCs) 17. In addition, conservation efforts on personal lands and networks have intensified in recent years18.19 by expanding wildlife habitat, buffering AP, cutting border effects, gaining better representation of ecosystems, securing seasonal migration spaces and particularly attracting and reaping benefits to rural communities living with wildlife.20 Array 21.22. In Namibia, network reserves total 170,000 km2, and in South Africa, hunting ranches cover a 205,000-square-kilometer canopy, either exceeding the dominance of the land covered through state AP19,23. Community-based conservation systems (CRCs) have evolved over more than 20 years, helping millions of rural African livelihoods.22,24

Despite an impressive political commitment to conservation in Africa, the continent suffers from severe and consistent investment scarcity that are consistent with the effectiveness of control. State-owned savannah APs in Africa with lions face recurring budget deficits of $1.2 billion consistent with the year, making wildlife vulnerable to threats, while forest APs are probably no longer protected11. The main threats come with habitat loss, degradation, fragmentation, invasion, poaching and climate change25,26,27. These factors, combined with poor governance, poverty, the expansion of human populations, and the illegal wildlife trade, continue to drive wildlife decline across the continent11,28,29,30. In particular, the loss of giant mammals compromises the functioning of ecosystems31,32. Therefore, with a few exceptions, African conservation in crisis even before it hit COVID-19. The pandemic can simply magnify the crisis to a catastrophic effect.

Researchers have documented some positive environmental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, lower commercial activity and mechanized transport have reduced global emissions and air pollution33. Some Asian countries (including China and Vietnam) have taken steps to limit the industry it threatens. If regulated and enforced in the long term, such limitations may simply reduce poaching in Africa of illegal products that supply from Asian markets. Gabon banned the intake of bats and pangolins after the COVID-1934 crisis. Traffic restrictions due to blockages can curb the product industry and generate a respite for APs suffering the negative effects of tourist congestion.

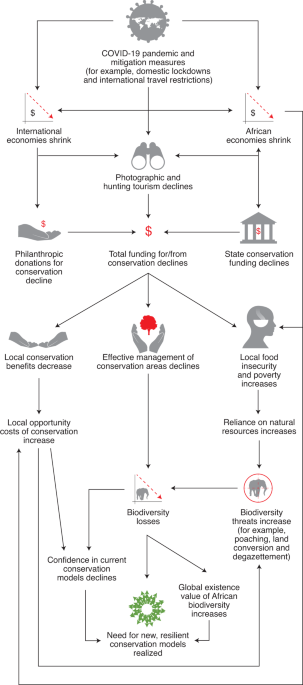

These positive environmental outcomes are likely to be maximum to be transient and are likely to be reversed when travel restrictions are reduced and countries resume their overall activities. We argue that the net environmental effect of the COVID-19 crisis in Africa will be very negative, as the crisis creates a “perfect storm” of reduced funds, reduced conservation capacity and increased threats to wildlife and ecosystems (Figure 1). . Wildlife conservation is possibly facing its biggest serious challenge in decades.

The arrows indicate the directionality of the effects among the other elements of the African conservation framework.

Governments face severe budget crises due to the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and the charge of relief measures. Scarcity will force policymakers to eliminate what is perceived as “non-essential” 4. The budgets of the already largely inadequate African wildlife authorities risk further shrinking, endangering wildlife and wildlife.

Added to this is the collapse of wildlife-based hiking across the continent due to travel restrictions and travel considerations (Figure 2; Table 1). While past uproats, such as the 2014 Ebola epidemic and the 2008 currency crisis, have particularly reduced hiking in some African countries, the negative effects of COVID-19 on industry across the continent are of unprecedented magnitude and severity35. Approximately 90% of African tour operators experienced a drop of more than 75% in bookings36. Since hiking is the main contributor to AA investment in some countries, loss of profit has major ramifications for national wildlife authorities, personal owners and traders, and network conservation systems (Figure 1 and 2) 37. The decline in hiking profits threatens millions of jobs and peripheral industries, with a serious effect on the livelihoods of some of the continent’s poorest other people (Table 1). For nations less dependent on wildlife hiking for conservation (e.g. in forest biome), the effect will be less. However, if the industry is slow to recover, the little-visited access points that come with emerging hiking products may be the last to receive visitors.

“Africa’s landspaces” refer to all landspaces classified nationally in Africa15. The source for each of the examples is shown in the following table 1.

In addition to the loss of tourism revenue, we expect to reduce donor investment for African conservation over the next 1 to 2 years and perhaps more due to declining economies and conversion priorities. During the last global monetary crisis, total charitable donations in the United States fell by 7% in 2008 and 6.2% in 200938, and conservation donations decreased by 40% to 39. Existing economic recession and volatile inventory market, to an even greater degree, can diminish the ability of personal donors, businesses, and foundations to make philanthropic donations. Travel and meeting restrictions have resulted in the cancellation and postponement of key meetings and conservation fundraising events. Many zoos are closed and declining revenue is likely to be to restrict aid for on-site conservation efforts. The pandemic will also divert attention from conservation to humanitarian causes. Some bilateral and multilateral donor agencies have invested more in emerging countries in reaction to the 200840 monetary crisis, however, the scale of the demanding economic and humanitarian situations in place is such that any additional investment is likely to be directed to these areas. Some emergency investments in conservation are organized in reaction to the crisis36, and it is highly unlikely to be to compensate for the losses.

People living on the outer edge of APs suffer from food insecurity, governments overlook them, and rely heavily on herbal resources96. However, they are the potential users and custodians of herbal resources. They support conservation prices (e.g. through conflicts between humans and wildlife, exclusion of herbal resources and, in some cases, land loss), without good enough profits. For decades, network environmentalists have tested business models and participation to empower local communities to own and manage herbal resources in the ecosystems where they live.97

The COVID-19 crisis calls these models into question. The effects on the conservation of the tourism network and industry have major economic implications for communities3. Loss of tourist benefits and trophy hunting can increase conservation opportunity prices and the threat of land conversion. The sudden loss of wildlife gains can simply erode the trust of communities, personal owners and even governments in wildlife conservation as a reliable land use option. Restrictions on movement and social estrangement regulations diminish engagement between conservation teams and communities, undermining the effortless acceptance of local populations98.

In addition to the loss of tourism revenue, rural communities face monetary difficulties due to the broader economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and government responses. In some areas, cattle markets have been closed, cutting off the source of income for rural communities. Nearly 20 million jobs are threatened on the continent if the crisis continues.3 As a result of the unemployment caused by the closure, others may return to their rural homes, as has been observed for transnational workers, many of whom have returned to communities adjacent to the Palestinian Authority near foreign borders99.

Increased poverty and lack of food confidence are likely to contribute to increased conservation risks. In the absence of monetary capital reserves, rural Africans with food insecurity can simply be lured to the outer edge of APs to take advantage of herbal resources100. The expected effects come with the construction of poaching, the felling of trees for wood and coal, artisanal mining, the invasion of AP through other people and livestock, and the conversion of the habitat of herbs101. We expect the risk of increased meat intake from wild animals to be serious, with anecdotal evidence reported in Tsavo East National Park (https://go.nature.com/32rNQYH). These risks will coincide with relief in funding, operational capacity and presence in the Community Conservators’ Room, national authorities, landowners, conservation NGOs and tourism and hunting companies.

Following the emergency reaction to the crisis on the outer edge of the APs, new models linking conservation and progression will be needed.

The reduction in investment is likely to be to restrict the ability of conservation professionals to manage APs and other conservation landscapes, force the dismissal of a key group of workers, and prevent them from purchasing indispensable supplies35 (Figure 1 and 2, Box 1). In addition, COVID’s restrictions on the movement of others undermine the ability of professional agencies to adopt their conservation work, as reported through the prolonged network of cash colleagues in the organization of authors (fig. 1 and 2). Some blocking policies in African countries save you all that is still “a must-have service.” In general, combat opposed to poaching seems to be allowed, however, the rotation of personnel and the source of consumables essential for guards on the floor can be interrupted, resulting in exhaustion and a minimisation of the morale of the guards (Figure 1 and 2). Policies that save you operations and activities that are considered unsusable can have a significant effect on network conservation, which is based on normal meetings, interactions and collaboration between various stakeholders, without access to remote communication technologies (Table 1).

The herbal resources and ecosystems that produce them are under increasing pressure as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Falling tourism incomes and the negative economic effects of the pandemic are likely to contribute to the rise of rural poverty. At the same time, COVID-19 constraints and budgetary constraints will hamper conservation operations. Therefore, as detailed in Figure 1 and Box 1, we anticipate an increase in poaching, tree felling, artisanal mining, AP invasion, agricultural conversion, and, in all likelihood, final degassing of the maximum apEs affected. With many ecosystems and populations already near tipping points, the existing crisis can lead to a population decline, local extinctions of some species and intensified alterations in ecological processes6.

The COVID-19 pandemic, such as SARS-CoV 1 and Ebola outbreaks, is most likely due to human intake of wild animals. Living markets create opportunities for pathogens to infect domestic or naive human species and cause new diseases41,42. In Africa, particularly in the biome of tropical forests, wild animal meat markets disclose human populations to species known as the most threatened to spread pathogens, such as primates, bats and rodents43. The combined effects of reducing conservation efforts and increasing poverty can create a positive feedback cycle in which increased reliance on herbal resources stimulates human invasion of herbal habitats, increases exposure and intake, and increases long-term pandemic threats44. In contrast, the effective conservation of species and habitats has been directly linked to the minimisation of the number of viruses that animals are affecting with humans45. Appropriate disease surveillance systems, particularly for the interface – habitat-human, want to be developed and supported by emerging hot spots46.

The conservation crisis facing Africa should not be overlooked, even when governments and NGOs respond to the humanitarian and fitness crisis. While the existing focus on aptitude and economics is essential, a long-term attitude is vital. Support for conservation efforts will help national and local African economies recover from the devastating effects of COVID-19 by diversifying and strengthening economies, creating jobs for rural citizens, and protecting ecosystem services. Protecting wild habitats from invasion can also help address one of the main fundamental reasons for emerging zoonotic diseases, thereby reducing the threat of long-term pandemics. Reducing aid for African conservation at this critical level can mark decades of progress. Here we describe the steps needed to protect African wildlife and landscapes and related rural populations and beyond the COVID-19 crisis. We describe the necessary movements to (1) manage the immediate crisis; (2) combat the destruction of the environment and address the continuing threats of habitat destruction and illegal, unsustainable and/or harmful wildlife industry; and (3) systemic deficiencies of the correct type in the existing conservation model.

Conservation in Africa will fail unless the foreign network intervenes to provide crisis financing, identifying conservation as an essential service and APs as global public goods. The evolved world is implementing mechanisms to rescue affected companies and industries, which in the United States amount to billions of dollars. However, governments in emerging countries facing cash do not have this potential. Moreover, there is no such mechanism to assist conservation in particular. Donors can simply register in combination to create an emergency fund for wildlife authorities, communities, landowners and conservation NGOs. In addition, the key industries that underpin conservation efforts, such as tourism, want help, either through tax exemptions and direct monetary assistance, provided they can demonstrate continued investment in the coverage of the wildlands on which they depend. In reality, the evolved world deserves to be the main source of this financing, coming from multilateral and bilateral institutions, businesses and the public. International philanthropic foundations have the opportunity to intervene, make a transformative difference to conservation in Africa and help avert catastrophe.

The prestige quo will not be imaginable for practitioners of maximum conservation during the crisis. They will require the development of strategic plans to prioritize critical activities and minimize the threat of “exceeding”. They deserve to focus on maintaining critical operations and retaining as many personnel as imaginable, so they can expand when the crisis subsides. Conservation practitioners and giant NGOs in particular want to reduce waste and excess. NGOs deserve to prioritize staff salaries in Africa where imaginable, and point out that wage coverage systems sometimes do not exist on the continent.

China and Vietnam have taken steps to limit industry and wildlife intake in reaction to the COVID-19 epidemic. Governments and organizations around the world deserve regulations and enforce existing legislation to take strong action against harmful wildlife business practices that endanger human fitness or conservation goals. Commercial constraints deserve to be appropriate, proportionate and implemented with local club and political commitment. Otherwise, the unsustainable or harmful industry could resume as soon as the rapid crisis disappears. However, efforts to eliminate harmful and unsustainable practices should not undermine legal parts of the wildlife industry that are or may be well regulated, pose a controlled threat of disease transmission, and help millions of people make a living47.

In addition to addressing the threat of disease transmission from the wildlife trade, governments and organizations face other hotspots in the emergence of infectious diseases, adding habitat destruction, which can be induced through commercial agriculture.44.48 In the forested regions of On the continent, logging and mining invade remote areas49 ,50, which probably facilitates the spread of the disease in and between human populations, as seen in the Amazon51. Forest regions urgently want flexible financing mechanisms to prevent the sale of forest concessions and the structure of progression corridors through unsustainable extraction of herb habitat resources. These measures can also help protect indigenous peoples from disease and the loss of their ancestral lands.

The COVID-19 crisis highlighted the fragility of conservation efforts in Africa and the basic deficiencies (Fig. 3).

Improving the duration and diversity of investment can simply increase resilience and efficiency. For more details, see Table 2. Photo credit: Morgan Trimble.

The fundamental investment of conservation through African governments is sufficient. Many countries face maximum poverty rates and lack the luxury and wealth of keeping African wildlife alone. Currently, the overuse of short-term ad hoc external investment resources (including philanthropy) is neither feasible nor safe. Many APs have an uns married source of inadequate investment. Tourism is a promising but insufficient source of investment in conservation. The over-reliance of some African countries on foreign tourism to aid conservation creates vulnerability to stochastic events. Few have enough budget in reserve to finance conservation operations during difficult times. Other countries do not gain any advantage from wildlife tourism (Figure 4). Where tourism thrives, communities that support wildlife prices gain negligible advantages, discouraging conservation.

Africa’s Land Ecoregions 91. b, Percentage of treetops with a cup density of more than 10% in 200092 (source: Hansen / UMD / Google / USGS / NASA). Countries are labeled with their ISO-3 codes. c, Wealth of mammal species 93. (d) Funding gap in national space networks in States with African Lion Diversity11. e, The average number of annual arrivals of foreign tourists to African countries from 2016 to 2014. (f, GDP consistent with the capita (adjusted by purchasing force parity (PPA)) in existing US dollars from African countries in 201895. In Jf, countries are full of white where no knowledge was available and values were categorized using the Jenks Natural Break method.

There is also a lack of systematic, long-term and sufficient conservation for the African conservation of northern countries, which derive great benefits from African wildlife and land, without contributing sufficiently to their costs. In relation to their wealth, some African countries bear a disproportionate burden of their conservation efforts and, therefore, the foreign network deserves to stock up at proportionate levels, noting that Africa’s herbal treasures are global assets; Africa’s environmental facilities gain global benefits through carbon sequestration; and African ecosystems play an important role in protecting human physical and intellectual health11,12,13,52.

More fundamentally, there is inadequate alignment between conservation and human progression programs. Here, we describe emerging opportunities to reconsider and restructure conservation investment in Africa for long-term resilience (Figure 3).

Africa is varied and has a diversity of contexts in which conservation is desired. Therefore, the answers we propose will have to be adapted (Fig. 4).

Effective long-term conservation in Africa is based on locating sufficient investments and strengthening political and public will. Harmonizing conservation and progression interests can be on both fronts. African economies rely heavily on ecosystem services, so this alignment can be supported in a number of ways, including:

Quantify the price of herbal assets and ecosystem facilities and incorporate those prices into national budgets, balance sheets and the development of plans for the use of herbal resources at the conservation price.

Position APs in their broader landscapes as centers for local development, service delivery, and even crisis relief. This was achieved through collaborative control partnerships for some African APs17,24.

Have proper interaction with other local people as conservation stakeholders. Within APs, create forums that allow communities to participate in A.A. ensure that communities gain benefits from tourism for their interaction. Outside of APs, publicize policies that move resource and wildlife rights to communities to help sustainable control and facilities that enable communities to maximize their economic opportunities53.

Encourage conservation organizations to paint with visual progression experts for key livelihoods of networked paintings, such as livestock and plant production, gaining public and expanding the resilience of local communities to impacts such as the COVID-1922 pandemic. For example, if conservation organizations offer security or markets for livestock, other local people will link those benefits to conservation; The “Health Breeding” program is testing this technique in northern Kenya and southern Africa54.

Since foreign conservation organizations are limited by travel restrictions, national conservation organizations and civil society efforts have the opportunity to fill the gaps. International partners deserve other people and local facilities by offering investments and sharing their expertise remotely. Once the crisis has subsided, local conservation capacity will be greater and can continue to be sustained, as well as the renewed efforts of foreign NGOs.

The volatility of foreign tourism and the decline of trophy hunting demonstrate the desire to create local sources of income that deal with global shocks (fig. 3, Table 2). Only a handful of African countries get a really important source of income from wildlife tourism16. Others want to unlock the prospects of tourism through investment in infrastructure and wildlife coverage and the creation of a tourism-friendly environment55.56 (Fig. 3, Table 2). By contrast, some countries in South and East Africa that rely heavily on foreign tourism deserve to inspire domestic tourism to develop resistance to global crises and long-term public aid for conservation57.58. With the trophy-hunting industry supposedly declining, partly due to the tension of Western trophy-hunting advocates, the DPs that lately depend on trophy hunting revenue deserve to seek income-hunting resources59. Given the serious investment deficiencies for conservation in Africa (Figure 4), the collapse of the trophy-hunting industry in the absence of options has serious branches for conservation in giant areas16.59. Richer countries will have to contribute to the status quo of choice and an advanced source of revenue-generating mechanisms to help pay for control and opportunity prices for Africa’s vast network of semi-protected areas. In some contexts, the breeding or sustainable use of wildlife would possibly be compatible with conservation60.61. In South Africa, a biodiversity economics strategy promotes bioprospecting and rearing of game animals and exports of meat, skin and leather as key income source resources that complement ecotourism62. Africa is developing at an immediate pace and governments deserve to use the “biodiversity mitigation hierarchy” to reduce ecological damage and ask for compensatory bills to generate a sustainable source of conservation income63.

Ultimately, for wildlife and wildlife to reach their economic potential, African governments will have to invest enough to protect their own assets. Once the crisis subsides, African countries can identify a constant budget allocation for the shield of nature, similar to the Maputo Declaration on Agriculture and Food Security 2003. National governments can also create a grant budget with the help of foreign investment, impose a hierarchy of biodiversity mitigation, and expand green and blue bonds.

If more national investment is desirable, much more money is needed on top of that. Emerging mechanisms for foreign governments, businesses, U.S. and NGOs to provide investments come with investments in protected areas and network lands, environmental and cultural service bills, and debt-to-nature exchanges (Table 2).

Africa wants to advance mechanisms to generate and disburse wildlife-related income well and offset indirect and direct wildlife opportunity prices. These mechanisms should recognize the role of Governments, landowners and communities in Africa as custodians of global wildlife resources. Examples include: (1) direct invoices through rich countries to African nations to separate wilderness areas, such as invoices made through Norway to Gabon64; (2) land leases, under which land is rented to the owners and set aside for conservation to avoid conversion to a land use less respectful of biodiversity, as is the case, for example, in the reserves around Maasai Mara65; (3) biodiversity management systems that pay or inspire homeowners to practice conservation-friendly land management; (4) functional payment systems that praise other locals for wildlife conservation (as is being tested lately in Mozambique, Namibia and Tanzania, for example, http://wildlifecredits.com); (5) “basic conservation income” compensating communities that protect nature66; and (6) systems and movements that mitigate the burden of coexistence with wildlife67.

The COVID-19 crisis threatens conservation efforts in Africa with a “perfect storm” of reduced funding for conservation, exhausted control capacity, the collapse of community-based herbal resource control companies, and increased threats. The crisis calls for a concerted foreign effort to protect Africa’s wildlife and wildlife and the others who have them. African governments, the foreign community, donors and conservation professionals deserve to paint in combination through decisive efforts and adaptive control to minimize negative impacts. At this critical stage, the prestige quo may be catastrophic, but decisive and collaborative action can ensure that African wildlife survives COVID-19 and that the most resilient conservation models gain benefits for humans and wildlife for generations to come.

A.C. and N.G. were supported by the EU-funded allocation ‘ProSuLi in TFCA’ (FED/20 I 7/394 -443) and the RP-PCP study platform (www.rp-pcp.org). A.D. supported through a grant from the Recanati-Kaplan Foundation.

Mammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Peter Lindsey

Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan, Queensland, Australia

Peter Lindsey

Wildlife Conservation Network, San Francisco, California, USA

Peter Lindsey and Paul Thomson

Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

James Allan

Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Peadar Brehony

University of Oxford, Tubney, United Kingdom

Amy Dickman

Institute of Communities and Wildlife in Africa, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Ashley Robson

TRT Conservation Foundation, Rondebosch, South Africa

Colleen Begg

World Bank, Washington, DC, USA

Hasita Bhammar

Deutsche Gesellschaft for International Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Eschborn, Germany

Lisa Blanken

WWF Germany, Berlin, Germany

Thomas Breuer

Conservation Capital, Nairobi, Kenya

Kathleen Fitzgerald

Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Gaborone, Botswana

Michael Flyman

Department of International Conservation Affairs, Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, Harare, Zimbabwe

Patience Gandiwa

Faculty of Agronomic and Forestry Engineering, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo, Mozambique

Nicia Giva

Kenya Wildlife Conservation Association, Nairobi, Kenya

Dickson Kaelo

Wildlife Conservation Society, Uganda Country Programme, Kampala, Uganda

Simon Nampindo

Secretariat of the Cross-Border Conservation Area of Kavango Zambezi, Kasane, Botswana

Nyambe Nyambe

Independent Consultant, Johannesburg, South Africa

Kurt Steiner

Conserve Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa

Andrew Parker

International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), London, United Kingdom

Dilys Roe

IUCN Panel on Sustainable Use and Livelihoods (SULi), London, United Kingdom

Dilys Roe

Independent Consultant, Cape Town, South Africa

Morgan Trimble

ASTRE, Uni Montpellier, CIRAD, INRA, Montpellier, France

Alexandre Caron

Veterinary Faculdade, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo, Mozambique

Alexandre Caron

South Rift Landowners Association, Nairobi, Kenya

Peter Tyrrell

Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

Peter Tyrrell

PL, JA, PB, AD, AR, CB, HB, LB, TB, KF, MF, PG, NG, DK, SN, NN, KS, AP, DR, P. Thomson, MT, AC and P. Tyrrell helped conceptualize, draft and edit the article.

The authors claim to have competing interests.

Editor Springer Nature’s note remains impartial in relation to jurisdictional claims on published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional 1 and references.

Reprints and permits

Received April 22, 2020

Approved: 10 July 2020

Published: July 29, 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6