Advertising

Supported by

Infused with new firearms, cities are linking the tension of the coronavirus to an increase in homicides.

By Thomas Fuller and Tim Arango

OAKLAND, California – Aaron Pryor’s circle of family and friends say they may never know precisely why the 16-year-old star football player, an ultra-fast ball carrier, died in broad sunlight on a Sunday in September in an alley near his Oakland House. Video of the shooting observed through the circle of relatives shows an assailant, who has not been arrested, confronting the teenager in the bathroom face before firing more than a dozen shots.

But his football coach, Joe Bates, doesn’t hesitate to blame him: with school completely online and football season canceled, the coronavirus turned the young man’s life upside down, Mr. Bates. , three-hour workouts, Friday night games, all of which disappeared this fall. In a general year, Mr. Pryor would have been on the field, not on the street, the coach said.

“It was Covid who killed that child,” he says.

Like many U. S. cities, where economies have been devastated by the pandemic, Oakland has noticed an increase in gun violence, adding six child murders since June and 40% homicides overall. is just as bloody, with the city on the brink of more than three hundred homicides for the first time since 2009.

Beyond California, major cities from Minneapolis to Milwaukee through New York, and even smaller communities like Lubbock, Texas and Lexington, Ky. , face the same sinister pattern, with some places, such as Kansas City, Missouri and Indianapolis, setting records. Philadelphia, which underwent a riot this week after police fired on a black man, is among the cities with the largest build-up of homicides: its 404 murders this year constitute a build-up of more than 40% over the same time last year.

Criminologists who read the increased homicide rate point to the effects of the pandemic on everything from intellectual fitness to police surveillance in an era of social estating, with fewer officials than normal for network paintings. Time has helped mitigate violence. Experts also characterize increased gang violence and an increase in ownership of homes with guns, adding to many homeowners with guns for the first time.

America’s homicide epidemic looms in recent days of a polarizing electoral crusade that President Trump has tried to provide as a referendum on law and order. Their constant chorus: Democrat-led cities have allowed crime to get out of hand.

But knowledge shows that waves of murder have affected cities led by Democrats and Republicans.

“Construction has nothing to do with the political affiliation of its mayor,” said Richard Rosenfeld, professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Dr. Rosenfeld studied the criminal tendencies of the pandemic for the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan study organization, and found that homicides increased by an average of 53% in 20 major US cities. But it’s not the first time During the summer.

Jeff Asher, a crime analyst in New Orleans, said the buildup of murders affects every single corner of the country and pointed to several Republican-led cities that have noticed sharp increases: Lubbock, who has noticed 22 homicides, by comparison. nine at the same time last year; Lexington, where homicides increased by 40%; and Miami, where homicides have increased by almost 30%.

“Because the pandemic tension is everywhere, it’s everywhere,” he said (Mr. Asher published some of his in the New York Times).

In Yaland, shootings are not as unusual, involving dozens of block-sprayed cartridges, which the Oakland police union leader and the city’s interim police leader have compared to a war zone.

For Guillermo Céspedes, head of the city’s violence prevention department, Oakland now evokes the region of the world in trouble: Honduras, El Salvador and other countries where gang violence is endemic.

“Just before Oakland, I run in Central America,” Chief Céspedes said, “and it’s harder. “

“I’ve been in this business for 42 years and I’ve never experienced anything like this,” he says.

Many of the teams that Chief Céspedes has deployed throughout his career, adding assembly with the families of the victims, comforting them and, most importantly, seeking to save them from the murders in retaliation, have been dulled through the pandemic.

“You don’t have to go near this family,” he says. They have to see your eyes, they have to feel your heart, they have to feel who you are and you have to feel who they are. “

Chief Céspedes said he seeks to perceive why many of the same spaces affected to the maximum by the coronavirus in Alameda County, which includes Oakland, also had the highest levels of violence.

A study published this month through researchers from the University of California, Davis, estimated that another 110,000 people in California bought weapons this year because they were involved in the destabilizing effects of the pandemic. to be corroborated through this year’s wave of gun background checks, about 95,000 more than last year. And those are just weapons received through legal channels. Los Angeles has noticed a 45% increase this year in the number of weapons stolen from cars, some of which have given the impression in shootings.

At a virtual police commission assembly, Michel Moore, the head of the Los Angeles Police Department, spoke of the “erosion” of the city’s successes in reducing gun violence in years. He said homicides in central and southern Los Angeles increased by approximately 50%.

“We are seeing more weapons, more people with weapons and conflicts that degenerate into gun violence,” he told the commission.

He said the branch was still analyzing knowledge of why there had been so many homicides, but noted that this was a trend line across the United States, and probably exacerbated through the pandemic, which affected the network systems that are credited with assisting young people. crime.

“These are the main periods of stress,” said Professor Nicole Kravitz-Wirtz, study leader at the University of California. “When you carry a firearm in those situations, it poses a fatal risk. “

Dr. Kravitz-Wirtz says that by exacerbating “poverty, unemployment, lack of resources, isolation, depression and loss,” the pandemic has “aggravated many underlying situations that contribute to violence. “

In addition to the destabilizing effects of the pandemic, widespread public reporting by police following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis could have had an effect on the accumulation of violent crimes, Dr. Rosenfeld said.

He noted that after the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, following the police shooting of Michael Brown, homicides also increased in U. S. cities. Some analysts have called it the “Ferguson effect” and have presented two explanations that can help the increase in homicides: that police have withdrawn from patrols in some neighborhoods and that neighbors, especially in communities of color, have police for mistrust, leading to a greater number of violently resolved disputes.

His studies revealed that other categories of crimes, such as residential burglaries, thefts and drug-related crimes, reduced the pandemic.

In California and many other parts of the country, increased firepower has also been a major component of history. Strict state gun law restricts the use of firearms in public and prohibits attack weapons, among many other restrictions. These laws are circumvented by bringing weapons from neighboring states with more permissive gun legislation.

Oakland police officers confiscated 1,000 illegal weapons this year, 37% more than last year. Through a partnership with federal authorities, the police branch traced many of those weapons to Utah, Nevada, and Colorado.

Police also seized illegal ammunition drums capable of firing up to a hundred rounds.

“The story is rarely very fair about who dies and who gets shot, it’s the number of shots,” said Oakland Interim Police Chief Susan E. Mr. Manheimer.

Buildings and cars were bombed with bullets. Two bullets hit the home of one of the city’s police commissioners and broke the families’ canteens while eating, Chief Manheimer said. And the police pressed shootings in which dozens of bullets were fired. combat shootings,” he says.

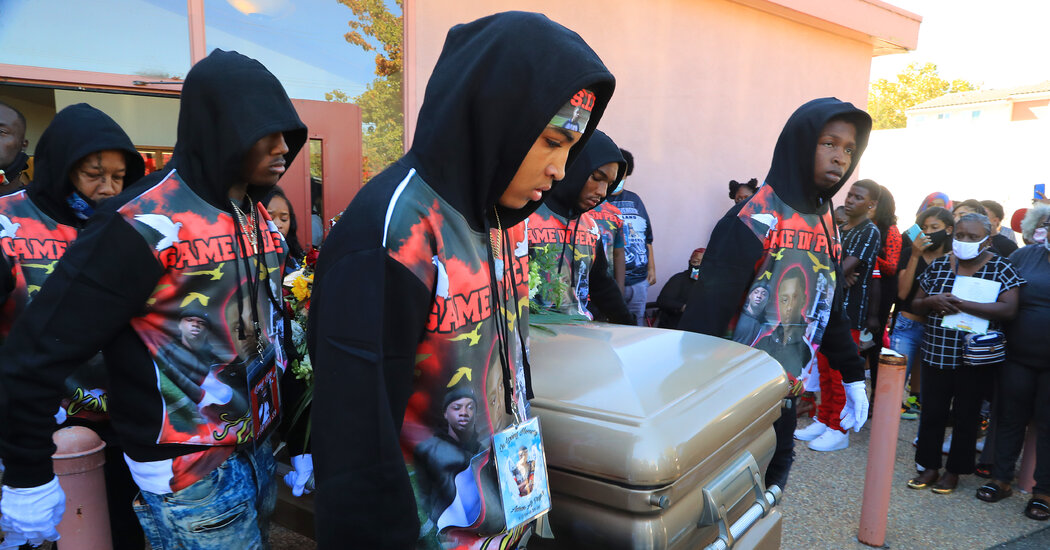

At Mr. Pryor’s funeral, held in a peach beige stucco church on a hot Saturday afternoon, a pastor, Mustafa Muhyee, spoke of the child’s promise and leadership.

“When you have to bury your children, you bury your future,” he said.

The boy’s father, Taijuan, hysterical in pain, sobbed as his friends and brother helped him walk to the church yard.

Mr. Pryor armed himself with courage and stood in front of his son’s teammates. Would you need it for your teenage years?

“It comes from my heart, ” Mr. Pryor, “put those guns down. “

Advertising