On the day she was scheduled to confront her son’s killers, Glaucia dos Santos got up early, straightened her hair on a ponytail and donned a T-shirt emblazoned with one word: “Gratitude. “

It might have seemed like an unexpected selection given what she was about to do: 3 hours by bus from her home on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro to a downtown courthouse, where the two policemen who shot her dead, 17-year-old men, were staying. In 2014 they were tried for murder.

But she felt lucky.

In Brazil, where even the highest egregious abuses by police are rarely punished, trials like this were virtually unheard of. Against all odds, and thanks only to his own detective work, Dos Santos now had the possibility of obtaining justice.

His eight-year war for a day in court came amid a string of police killings that had made Brazil’s police one of the deadliest in the world.

Police killed another 6,145 people here last year, according to Brazil’s nonprofit Public Security Forum, an average of nearly 17 people per day and nearly triple the 2013 total.

Considering the length of the population, the police killed at a rate of times that of U. S. law enforcement. U. S.

In the state of Rio de Janeiro, police killings accounted for nearly a third of all homicides. Most held positions in the favelas, former squatter colonies founded by former slaves that remain predominantly black today and have a small audience and a strong gang presence.

The rise in police violence was celebrated through President Jair Bolsonaro, who pushed for legislation that would grant immunity to officials who dedicate murder in the line of duty and said that “a police officer who does not kill is not a police officer. “

His challenger in Sunday’s presidential election, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, has said little on the issue, with some political observers concluding that he is wary of a confrontation with police because of the option that only Bolsonaro in an attempt to borrow the election. However, if Lula, as he is known, becomes president, as polls suggest, he will face pressure from increasingly vocal segments of his base on the need for police reform.

While officials almost protect their killings as acts of self-defense from armed criminals, human rights teams and journalists have documented an exaggerated use of force, adding abstract executions of unarmed or injured people.

A United Nations report this year said Brazil’s security strategy demonstrates an “unacceptable for human life” and highlighted a deep racial disparity. Blacks make up 55 percent of Brazil’s population, but 84 percent of those killed by police last year.

When Dos Santos, who is African-American, lost her only son, Fabricio, she took on a new role in her community. Whenever another young man died, her mother came to her for help and advice. Over the years, a WhatsApp organization of grieving mothers he had created came to come with a dozen neighbors and even his own sister.

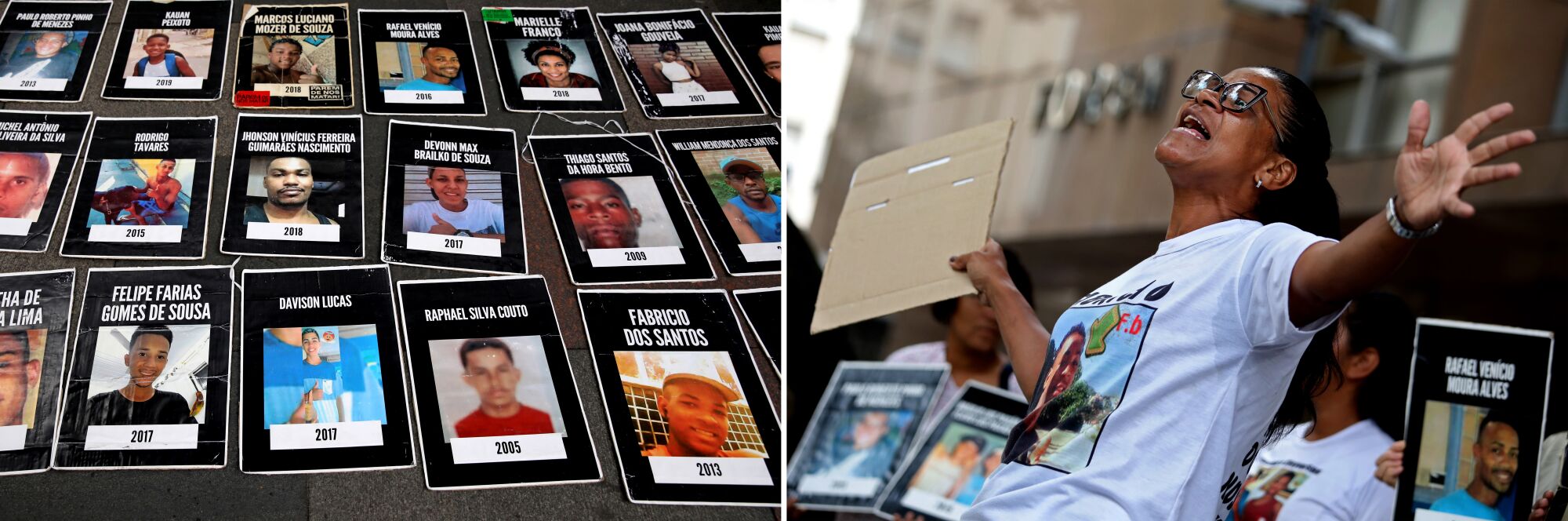

At the courthouse last month, Dos Santos, 46, was accompanied by several of them, each carrying a photo of his own dead son. For many, Fabricio’s case had been deeply private, as they knew it was unlikely they would ever have their own day in court.

The sun flew through the clouds as the side stood singing Fabricio’s call and what everyone wanted: “Justiça. “

“The police are meant to protect,” dos Santos told a crowd of others who had prevented them from seeing the impromptu protest, their voices trembling. “We need them to prevent them from killing us. “

Then she and the rest of the testified in court.

Dos Santos knew it would never be easy to raise a child in the favela.

His community, Chapadão, is a maze of small houses made of unpainted bricks and corrugated iron roofs that stretch across the hills north of Rio.

Fabricio’s father, a former military man, left when he was a Bavia and his mother worked as a housekeeper. When Fabricio was 3 years old, he collided with a truck speeding through the neighborhood, leaving him with a permanent limp.

For her shy son, who dreamed of becoming a mechanical engineer, life’s biggest fear isn’t ruthless teasing from his classmates or even gangs promoting drugs on the streets. It’s the police.

Officers harassed him at a local arcade and blocked the bus as he was on his way to a space portrait task in Copacabana. Once, he was taken to a police station for riding in a car that police said had been stolen, until they changed his story and let him go. .

Her mother pleaded with her and her two younger sisters to remain calm when the police were involved: “Never answer them. Don’t allow yourself to react. “

But Fabricio was terrified of the police, who had a reputation for brutality in the favelas since the 1970s, when the government launched a war on drugs and began going after gangs that had formed in Brazilian prisons and were now hiding in many slums.

There have been brief attempts at police reform, the advent of networked police outfits in some favelas in the few years leading up to the 2014 World Cup in Rio.

Although those efforts reduced police killings for several years, the special sets never made it to Chapadão and were eventually abandoned altogether. Murders began to rise; It was not unusual for another 20 people to die on a single afternoon when police raided his favela.

By law, police can use lethal force to deal with an “imminent threat. “

“But on the street, the law is different,” said Daniel Lozoya, a court-appointed lawyer in Rio de Janeiro. “He’s black, he’s poor, so the police shoot. “

At dawn on January 1, 2014, two police officers sat down with a police investigator about how and why they had just killed a young man. This was protocol whenever an officer used lethal force.

The policemen, Victor Declie de Souza, who is white and 31 at the time, and Paulo Renato do Nascimento Pires, who is black and 38, said they were patrolling near Chapadão a while before 3 a. m. when 3 men on two motorcycles started shooting at them.

Police said they chased the attackers about a mile from a gas station, where Declie used a rifle to shoot at a motive force as the other suspected attackers speeded away.

Officers said they discovered a Glock handgun next to the frame of the user they shot, who would later be known as Fabricio dos Santos. dead.

Investigators did not move to the crime scene because the community was “too dangerous,” records show. No forensic investigations were conducted to prove whether Fabricio had ever fired the gun. Police never sought witnesses to interview.

The case may have ended there, like the vast majority of incidents where police kill civilians here.

Rio de Janeiro state’s attorney general’s office said it did not track the number of prosecutions against police officers. However, several independent studies have shown that fees are charged in less than 1% of police killings.

Marfan Martins Vieira, a former attorney general, told human rights investigators that he believed many of the alleged shootings between police and civilians were “fake,” meaning only police officers fired shots, but that low-quality investigations leave prosecutors without enough data to uncover it.

Cesar Muñoz, a researcher at Human Rights Watch, said prosecutors have the authority to investigate police abuses, and they should.

“The police should not investigate themselves,” he said.

Dos Santos thought the police were lying. Her son, she told investigators, had never wielded a gun in her life. And she had seen him walking to the fuel station, after celebrating the New Year with his girlfriend. Moreover, she and her neighbors hadn’t heard a gunshot, just a single shot.

She was 3 months pregnant and suffering from morning sickness, but she was determined to find out the truth. “It was the least I could do for him,” she said.

After identifying Fabricio’s body, he went to the fuel station, where he discovered the workers who were there at the time of the murder. They shared evidence that would separate Fabricio’s case from many others involving the word of a witness opposed to the word of the police: surveillance footage.

The grainy video shows Fabricio filling his tank, putting air into his tires and preparing to leave the fuel station when a police vehicle stops. Fabricio turned around with his motorcycle and began to drive away from the patrol. Because he didn’t have a driver’s license and didn’t need trouble.

The patrol car follows, then, with Fabricio off screen but the vehicle still in the frame, there is a flash of light: a unique shot.

It was in January that Dos Santos presented the video to the media. Soon, news crews were filming the small demonstrations she was organizing in her neighborhood.

Under mounting pressure, prosecutors announced in June that they would charge the two officials with murder, accusing them of fabricating the story of the shooting and placing the weapon in Fabricio.

Staff members were allowed to continue working, even though they were assigned administrative tasks.

Dos Santos knew he had a long way to go. In Brazil, it can take up to ten years for a homicide case to succeed in court.

Every few months, she went downtown for some other hearing. It took years before an approved verdict on the case merited being presented to a jury. It took another opinion passed for months to evaluate the defendants’ appeal opposing that one. decision.

As he left the courthouse one day in 2016, Dos Santos saw a women’s organization protesting on the sidewalk. One of them spoke of her 19-year-old son, who had been shot in the back by police.

For dos Santos, joining the thriving action of mothers who had lost their children to police bullets was like finding a family.

Elsewhere, police violence began to get wonderful attention. In 2014, protesters took to the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, after police killed an 18-year-old black boy named Michael Brown. A hashtag spread on the Internet: #BlackLivesMatter.

In Brazil, the movement is growing, but more slowly.

Although slavery lasted here until 1888, more so than elsewhere in the Americas, Brazil has never experienced formal segregation like that of the United States, and the country has long viewed its history more through the prism of elegance than race.

Among the key figures in the burgeoning anti-racism movement was Rio de Janeiro councilwoman Marielle Franco. A single mother from a favela not far from Chapadão, passionate about preventing police abuses, whom she accused of acting as death squads.

In March 2018, he tweeted about a bloodbath in a favela: “They are coming to dismember the population!They are coming to kill our little ones! A few days later, she and her motive force were shot dead in downtown Rio.

The two men accused of his murder are former Rio police officers. They are awaiting trial.

Franco’s death intensified calls for reform. But the motion has provoked backlash.

Some argued that there may be no racial details in the killings, given that about forty-five percent of Brazilian police officers are black. Others said strict vigilance is needed, given Brazil’s fight against violent crime.

However, police killings were expanding much faster than homicides in general. And as homicides began to decline from their peak of 64,078 in 2017, law enforcement continued to kill in ever-increasing numbers.

The excessive peak trend in Rio, where police discovered a best friend in Bolsonaro, who was then a congressman.

His promise to crush criminals with an iron fist helped him win a national and propelled him to the presidency.

Shortly after taking office in 2019, Bolsonaro pushed through a law to protect the security forces that are being prosecuted and promised that criminals “will die in the streets like cockroaches . . . so to speak. ” The law was not passed, but many feared the president’s rhetoric would inspire police to act violently.

During his 4 years in office, police killings hovered around record levels.

Dos Santos remained unperturbed, despite the costs. When she felt guilty that by focusing on the case, she had less time for her 3 daughters, she thought she was doing it for them and the other young people in the favela.

He also went so far as to say that his activism was putting his own life at risk.

A friend from the favela who had lost a son to police bullets and worked to get a violent police officer out of his community received death threats and fled.

“The police come here to hunt,” said the man, who did not give his call for fear of reprisals. “Now I have no dignity. I have no life. I am a fugitive.

Dos Santos’ case dragged on for 8 years. But in the end, it was a close decision.

In Brazil, prosecutors and defense first provide the main points of their instances to a judge, then redo them before a jury in a quick trial that can end in a single day.

A few days before the start of the jury trial, Dos Santos stood in front of his favela waiting for the arrival of Guilherme Pimentel, the ombudsman of the public defender’s office in Rio. His taxi finally stopped and the two kissed.

Dos Santos had spent the morning walking around the community to get permission from gang leaders to allow Pimentel and a small delegation of government human rights officials to make contributions to the community.

They passed a checkpoint manned by an armed guard and settled into red plastic chairs arranged in a circle on the terrace of a café. “We want to know what happened here and how we can help,” Pimentel began.

Ronaldo Lacerda, a 28-year-old funk DJ with orange-dyed hair, described the shooting death of his 21-year-old cousin.

“I’m lucky,” he said. I will be dead too. “

Dos Santos was disappointed that Lacerda and his friends protested the killing by setting fire to a bus.

“It’s just to rebel. I get it,” Dos Santos said. But you have to have a strategy. A guy sets fire to a bus, and then that’s what ends up being shown on TV. They will use this symbol in the test.

The boy nodded.

Then spoke Sonia Bonfim Vicente, 37. Her husband and son were taking the son’s friend to the hospital last year when the 3 were shot dead by police. Only the friend survived.

As Bonfim spoke of his son, Samuel, who would enlist in the army the day after his death, dos Santos reached out and took his arm.

A public defender took note of Bonfim’s information. But he warned the crowd of too much hope.

“She is an exception,” public defender Maria Julia Miranda said of Dos Santos. “It’s very rare for an officer to have to do it because of their movements in court. “

Inside the courthouse, Dos Santos is taken to a domain reserved for testimony. She will be called to testify and recount the last time she saw Fabricio leave alone.

The officers faced seven years in prison if convicted of manslaughter and fraud for leaving the weapon.

A lawyer for one of them said the couple would argue they were shot through suspects on two motorcycles, no witnesses saw this and it was not visual in the video.

The other moms piled up outside the courtroom, waiting to be let in. But 30 minutes passed. Then an hour. The mothers nervously drank plastic coffee cups.

Finally, Dos Santos returned with slumped shoulders. The lawyer for one of the defendants did not appear. The sentencing had postponed the trial until April.

In short, Dos Santos was in the same room as the officers, who wore uniforms.

“They confided in me they weren’t running on the street,” he said.

“At least they don’t kill anyone,” one woman murmured.

“We have to come back next year and come back with more people,” she said.

Dos Santos left where she had been. The sky was cloudy and the wind was rising. A few heavy raindrops fell as she and her sister said goodbye to other moms and boarded a bus that would take them back to the favela.

L. A. Times Must-See Stories

Get the most sensible news of the day with our Today’s Headlines newsletter, which is sent out every day of the week in the morning.

You may get promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

To follow

Kate Linthicum is the Los Angeles Times’ foreign correspondent in Mexico City.

To follow

Gary Coronado has been a photographer for the Los Angeles Times since 2016. He is a finalist for the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in reportage photography for photographs from Central America who risk their lives and physical integrity while jumping aboard trains from southern Mexico to the United States and a 2005 Pulitzer. Finalist of the award in news photography for the policy of the hurricane team. He began freelancing for the Orange County Registry and moved to South Florida in 2001, when he won a grant from the Freedom Forum. Coronado grew up in Southern California and graduated from USC.

Subscribe to access

To follow