For 12 years, Berlyne Vilcant painted for the city of Newark, NJ, as a disease researcher, which means that when there is a cluster of cases of a specific disease: salmonella in a place to eat, for example, or norovirus in a hotel – your task is to find out how it started, who posted it, and how to prevent it from spreading further. A lifelong Newark resident, she grew up in a circle of Haitian immigrant relatives and, even as a child, knew she was looking for paintings in the field of fitness. As a teenager, animated through the character of a fitness inspector at a lunch spot in the 2003 film Free Us From Eva, she put herself in public form.

In January, Vilcant was occupied through non-unusual epidemics: hand, foot and mouth disease in a day care center, Legionella in a center for the elderly, remote cases of Giardia. When she told friends that she feared a new virus would tear China apart, they reassured her. Don’t worry, they said, you might not be coming here. But as Vilcant read other articles, he remembers thinking, “My God, if he makes it to America, I know he might not have a life. ” On Saturday, March 14, the manager of her fitness branch called to tell her that a user in Newark had tested positive for the virus. “My waist fell to the ground,” he recalls. “From that point on, I knew it was anything that was going to be serious, and we had to treat it like it was going to be here for a long, long time.

For the next two months, Vilcant saw his worst nightmare come true, when the virus took over his city. On the peak day of April 6, there were 162 positive control results. Intensive care teams at local hospitals have approached capacity. Vilcant and his colleague were the only two disease researchers hired in the city, and there was no way the two would call everyone who tested positive for the coronavirus. The fitness branch had to bring in seven place-to-eat inspectors to help. Vilcant’s premonition that the paintings were given the best of her life is true: As the city’s lead disease researcher, she painted from 6 a. m. at 11 p. m. seven days a week. He rarely saw his two school-age children.

During those days of fear, Vilcant felt that the long hours didn’t even make a difference. Around him, other people were in poor health and dying. Sometimes when a member of his team called someone to tell them they had tested positive for the virus, the reaction was hostile. How dare he say that his circle of relatives had let the virus in? Even those who sought to cooperate may not. In Newark, where 28% of citizens live below the poverty line, many stayed home for two weeks outside of consultation. As the pandemic progressed, it became clear that Blacks and Hispanics were vulnerable to severe cases and deaths from the virus; Those two teams represent 86% of the city’s population.

In the war against the coronavirus, Newark faced great possibilities. However, about two months after the pandemic started, something surprising happened: Cases in the city begin to decline. Furthermore, the trend has continued. In early May there were 50 to 60 cases almost every day, in June the numbers dropped to 20. It’s remarkable, especially given the city’s proximity to New York, where the virus is still raging.

Perry Halkitis, dean of the School of Public Health at neighboring Rutgers University, attributes the city’s initial good fortune to a combination of factors: Newark Mayor Ras Baraka showed strong leadership, reporting to the city all days at the town hall fair on Facebook. Live. The university’s public fitness school provided expertise and an organization of scholars willing to volunteer and paint alongside Berlyne and his colleagues. But probably the ultimate vital factor, says Halkitis, who helped coordinate the reaction to the Newark pandemic, the city’s investment in a specific strategy.

During an epidemic, infectious disease circles have a mantra: check, trace, isolate. That is, diagnosing cases, locating other people that each patient could have exposed, and quarantining other people who may not be fit until they test negative. The strategy, which has been subtle across public fitness personnel around the world for several decades, has been successful in controlling outbreaks of tuberculosis, SARS, MERS, and Ebola. As the last six months of the pandemic have shown, implementing this mantra is less difficult said than done. Most spaces in the United States still struggle with verification pass, let alone tracing and isolation. But almost as soon as COVID-19 hit Newark, leaders, possibly adding fitness officials and Rutgers experts, mobilized to build a monitoring, tracking and isolation infrastructure for the city. Halkitis said. “The smart thing for Newark was that all hands were on deck. “

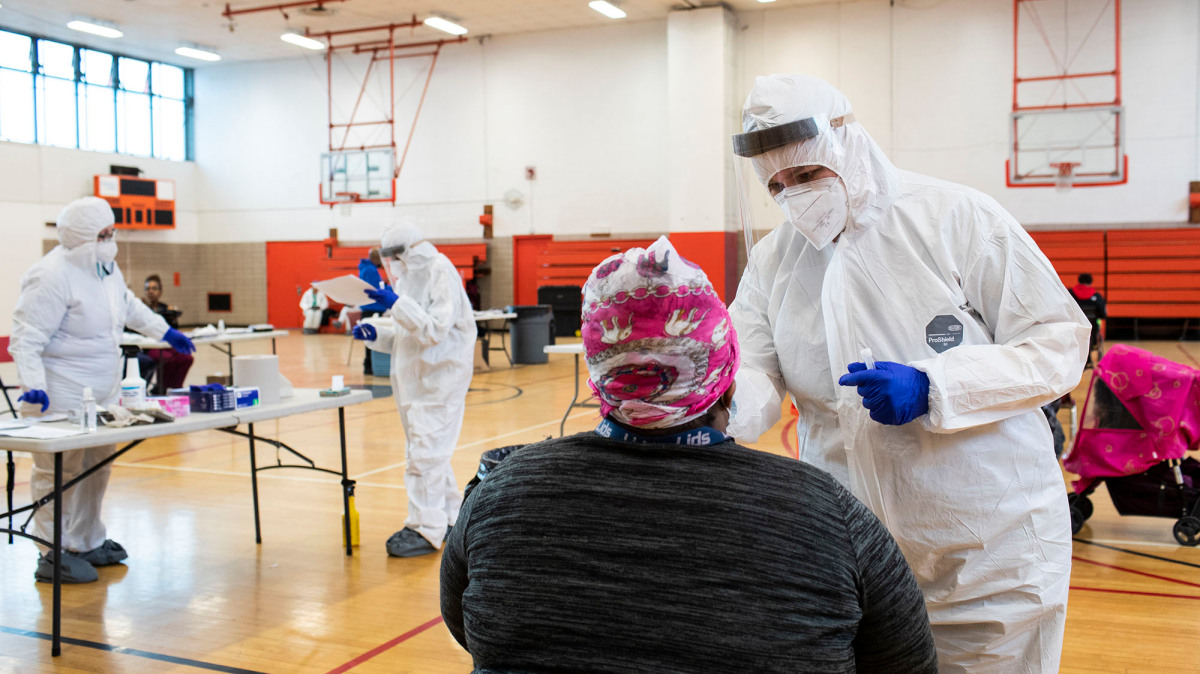

Amid the national shortage of controls for coronavirus, public fitness officials in Newark developed a strategy on the most productive way to use the small number of controls they had. The test sites in other cities were concentrated in affluent neighborhoods, however Dr. Mark Wade, director of the city’s fitness and network wellness branch, made the planned resolution to allow others without access to the Attention. Last spring, when it became clear that the coronavirus is serious in black and brown communities, the fitness branch opened more screening sites in minority neighborhoods and made a special effort to be successful in them. other older people who lived there. In other parts of the United States, cities have built direct access control centers, but in Newark, where many other people don’t have cars, the sites have also received patients on foot. The city also spent $ 2 million to establish a facility to check in another 2,200 homeless people at an airport hotel and to locate transitional housing for those who have been infected.

Hoping to get the most out of each of the valuable tests, Newark officials focused their efforts on touch-tracking. Because the cash-strapped city didn’t have the money to quickly rent a body of study, the fitness branch recruited volunteers. As of late April, the program was up and running, but city leaders were looking to improve knowledge gathering and put more force into the tracking effort. They looked to neighboring Massachusetts, whose state-of-the-art tracking program, the first and most ambitious in the country, was showing up as signs of success. The strength of the Massachusetts program was a global public fitness organization called Partners in Health, and its tracking approach combined thoroughly trained tracers and a complicated knowledge control system. With the help of an injection of cash from the state, Newark leased Partners in Health and partnered with the Rutgers School of Public Health to power its tracking system. Before long, the city rented 400 touch markers, many of which were Rutgers public fitness and nursing specialists.

Many of the classes learned through the PIH team in Massachusetts proved useful in Newark. For example, they worked with cellular operators to make the number on the touch tracker look like “COVID-19 information” instead of “unlisted”, for the chances of other people answering the call. But there were other more basic demanding situations that they had not faced in Massachusetts. The creation of test sites for the other most vulnerable people in the city, especially those from black and brown communities, has only solved one component of the problem.

A more serious factor is that many citizens were uncomfortable giving non-public data to touch tracers. Some had experienced discrimination in doctors’ offices, so naturally they were reluctant to share medical data with strangers. In Newark, touch trackers were under threat of posing as unbiased knowledge creditors – staff who were only interested in numbers, not other people. For this reason, staff were trained to make it transparent that the data collected was kept private. They have also been trained to pay attention and respond with empathy. “It’s not just about gathering knowledge,” said Katie Bollbach, the Partners in Health liaison who led the group’s team in Newark. “It’s about making other people feel supported and cared for. “

Bollbach, who had worked on Partners in Health’s Ebola response in Rwanda and Sierra Leone prior to the pandemic, told me that her transition to the United States was shocking, but not in the way you’d expect. Without delay, it was affected by limited access to physical care for many Americans. In Sierra Leone, one of the poorest countries in the world, Maximum’s villages had loose net clinics, as well as staff who went door-to-door to control outbreaks of infectious diseases among citizens. In America, this kind of fitness aid is unimaginable. “The emphasis on network care as the cornerstone of smart public fitness in Sierra Leone is truly amazing compared to our formula here in the United States,” he told me. “Here, we focus on fitness as a commodity, rather than a human right. “

What Partners in Health has learned over many years of studying outbreaks in Africa is that testing and tracing is unnecessary without the last step of isolation. Bollbach’s team in Sierra Leone found that the maximum number of inhabitants may simply not receive food and other essentials during the 21-day quarantine era necessary to prevent spread. Ebola virus. Therefore, the officials distributed cleaning materials (gloves, soap, bleach), as well as food, water and other materials to the estranged families. Initially, it was Partners in Health that provided the materials, then the government took over. In addition to the curtain materials, Partners in Health worked with the fitness branch to send staff to check on other quarantined people – how were they doing? Did anyone else in space have symptoms? These undeniable gestures raise the point of trust in fitness service. They are also more likely to have other people self-quarantine completely. The regular recordings, the team said, made other people locked up in their homes feel less alone.

Bollbach and his team brought those classes to Newark and created systems for others who needed to quarantine their homes. One of them was Wendy Pillajo, who lives with her parents, stepfather, husband and three-year-old daughter in an apartment in Newark. Pillajo, a medical assistant at an emergency care clinic, told me about his circle of relatives about the war with the coronavirus. In May, days after her mother attended a family circle meeting, all in her relatives, unless she contracted COVID-19. Relatives’ cycle of symptoms ranged from mild (their daughter had a fever for a day) to severe: Her parents had debilitating chest congestion, muscle pain, and abdominal problems. Surprisingly, Pillajo, who has been tested several times, has never had a positive result. A few months later, Pillajo’s mother tested positive on her back and the entire circle of relatives was once again quarantined for two weeks.

During a quarantine period, agents from the fitness branch called Pillajo’s family circle one day or the other to register. They would ask how one of the members of the family circle felt and if anyone needed anything. After Pillajo’s parents tested positive, they told the rest of the family circle how to get to a loose testing site. When Pillajo said he might have trouble getting his groceries delivered, the town sent hot meals: chicken, mashed potatoes, corn bread, rice. Pillajo told me that he enjoyed racing, but more than that, he was grateful to have someone to ask questions of. She was so worried about her father that she couldn’t focus on anything else. Through the daily recordings, “we understood what was happening and we saw that they were improving,” he said. “It helped me to know that they care about us. “

In August, Newark’s harsh paintings paid off. There were only a handful of new cases a day, drastically from more than a hundred a day to the peak in April. As Halkitis walked through the city, he saw that the culture of public fitness had taken hold. The citizens wore masks. They kept their distance from others. They obeyed at 9:30 p. m. curfew. “People take this very seriously,” he says.

If the extensive test, trace, and isolate strategy has worked so well in Newark and Massachusetts, why hasn’t it held up in the rest of the country? Halkitis believes that one of the reasons is leadership. From the beginning, the Trump administration has provided little comprehensive and reliable direction to respond to a pandemic, and many cities and states have been far from coordinated in their actions. In Newark, from the beginning of the pandemic, Mayor Baraka had the backing of New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy; their plans for the pandemic were aligned.

Other cities have not benefited from such a unified vision. In New York City, Mayor Bill De Blasio clashed with Governor Andrew Cuomo at the start of the pandemic; the governor scoffed at the mayor’s suggestion in March that he might want to close schools. As the leaders fought, the virus spread uncontrollably and, until the end of March, New York City became a zero point for the pandemic. In Atlanta, Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms took on Republican Governor Brian Kemp: He undermined him every step of the way, from relaxing regulations for the initial shutdown to suing over the mask he enacted. (He later withdrew the lawsuit challenging the mask ordinance. ) Today, in a CDC ranking of statewide coronavirus cases, Georgia ranks fourth in the country. State and local chiefs have stood alone, forced to navigate their coronavirus plans with little direction from the federal government. As President Donald Trump told governors in April, “They are going to make a decision. “

Another challenge with test-trace-isolate, says Halkitis, is that it doesn’t paint right away. There is a tendency, he said, “for much of the American public to need simple answers. ” In fact, this fantasy is evident in Trump’s insistence on selling supposedly miracle remedies like hydroxychloroquine. Again, this type of thinking goes beyond the existing administration. (How many times have you fantasized about what you would do when the vaccine arrives?) But in genuine paintings of the fight against infectious diseases, Halkite says, “This disease requires difficult paintings, and that means you have to give up some things. Array “.

Joia Mukherjee, Medical Director of Partners in Health, echoed his sentiments. “What is a shame is that in the United States we were surely not ambitious” in the search for contacts. But she sees Newark as a bright spot: “Newark is a very difficult position to work for,” she told me. “There is a lot of poverty. But the Department of Public Health has the same point of view as Partners in Health, namely: towards the vulnerable.

Vilcant feels a wave of satisfaction when he sees in the graph that the decrease in coronavirus cases appears in his beloved city. In early September, there were only a handful of cases that coincided with the day. In those moments, he feels that the complicated conversations, the logistical quagmires, the 70-hour painting weeks, were worth it. But the pandemic is not over yet and he knows it would be a mistake to lower his guard. “My researchers and my contacts have this mindset to go ahead and keep doing the paintings that they’ve been doing,” he said. After so many months, it is complicated. It is a marathon. Sometimes the young people of Vilcant tell him that they hate his task because it takes him away from them. “I have to tell them, ‘It may not be forever. In the long run, you will understand why Mom had to take time out of her family circle to spend my time making sure this procedure was completed. “

Subscribe to Mother Jones Daily to get our stories delivered straight to your inbox.

without free and fair elections, a relaxed press and citizens committed to reclaiming force from those who abuse it.

In this election year like no other, in the midst of a pandemic, economic crisis, racial reckoning and so much madness, Mother Jones’ journalism is driven by an undeniable question: Will the United States move closer or deviate from justice? and justice for years to come?

If you can, sign up for this project today with a donation. Currently, our reports focus on voting rights and electoral security, corruption, misinformation, racial and gender equity, and the climate crisis. We cannot do this without the participation of readers like you, and we have to give everything we have until November. Thank you.

without free and fair elections, a relaxed press and citizens committed to reclaiming force from those who abuse it.

In this election year like no other, in the midst of a pandemic, economic crisis, racial calculus and so much madness, Mother Jones’ journalism is driven by an undeniable question: Will the United States move closer to or deviate from justice? and justice for years to come?

If you can, sign up for this project today with a donation. Currently, our reports focus on voting rights and electoral security, corruption, misinformation, racial and gender equity, and the climate crisis. We cannot do this without the participation of readers like you, and we have to give everything we have until November. Thank you.

Subscribe to Mother Jones Daily to get our stories delivered straight to your inbox.

Save big on a full year of surveys and information.

Help Mother Jones dig deeper with a tax deductible donation.

No dear too! Sign up and get a full year of Mother Jones for just $ 12.

We are to your ears. Listen to Apple podcasts.

Subscribe to Mother Jones Daily to get our stories delivered straight to your inbox.