Your browser doesn’t display the article.

On the wealthy peninsula of Victoria Island in Lagos, Nigeria’s advertising capital, no one knows how much their food costs. Prices are changing so temporarily that stores have abandoned labels altogether. At the checkout, one might be surprised to notice that a tomato now costs 120 naira (8 cents). Last year, I might have given you four, enough to balance out the hot spices of a pot of Jollof rice. This staple dish has become even more expensive due to skyrocketing onion and rice prices, forcing poorer Nigerians to skip meals. Because Nigeria is dependent on imports, its weaker currency pushes the annual inflation rate to a three-decade high of around 30%.

Last year, 23 African currencies reached record levels of opposition to the dollar. The naira, which is on its way to floating completely, has been devalued twice in an attempt to close the gap with a parallel exchange rate in the market. This makes it the worst time. The best-performing currency in the world, after the Lebanese pound. This drop is also eating into the foreign exchange earnings of multinational companies. For example, MTN, a South African telecoms company whose largest market is Nigeria, said this month that its group’s profits could fall by 60 to 80 percent and that its Nigerian subsidiary would suffer a loss due to the collapse of the naira. Currency volatility erodes confidence, provokes protests from industrial unions, and deters much-needed investment.

For more than four decades, oil has provided Nigeria with a steady flow of dollars that has driven up the naira. In many cases, this made it less expensive to import things than to make or grow them. But oil production has fallen in the future. It’s been 20 years and no other primary source of export earnings has replaced it. Faced with a shortage of hard currency, Nigerians are terrified of dollars, putting even more pressure on the naira.

In a bid to curb inflation and attract foreign investment, the central bank, under new governor Olayemi Cardoso, raised interest rates to 22. 75% last month. The juicy rates have some impact: foreigners bought four-fifths of the short-term debt issued. through the central bank after the increase. The bank also claims to have late settled $2. 3 billion in foreign exchange transactions, frustrating airlines and causing multinationals to leave because they couldn’t get cash out of the country.

When Kenya raised interest rates in February and issued $1. 5 billion in bonds, its currency recovered. In Nigeria, however, demand is so great that emerging interest rates have shifted the needle less.

Taming the naira will require more than quick fixes and financial policy adjustments. “For the first time in a decade, we have a very transparent view of what [the central bank] is doing and why,” says Amaka Anku, who leads the Africa practice. at Eurasia Group, a political threat consultancy. ” But the central bank can’t make foreign currency!”

Nearly a year after Bola Tinubu was elected president, questions are being raised about his government’s ability to deal with a crisis of this magnitude. A new maximum tax on corporations that rent to expatriates (costing between $10,000 and $15,000 per year per foreign employee) is meant to discourage investment. And efforts to curb the currency hypothesis are distracting attention from the broader reforms needed to make Nigeria a good position to do business. Only when the country is able to sell more of its own goods and facilities abroad, or gain acceptance as with foreign investors to fill the void, will it be able to solve its chronic shortage of dollars?

This article appeared in the Middle East and Africa segment of the print edition under the name “Nary a dollar. “

Check out the stories from this segment and more in the list of topics.

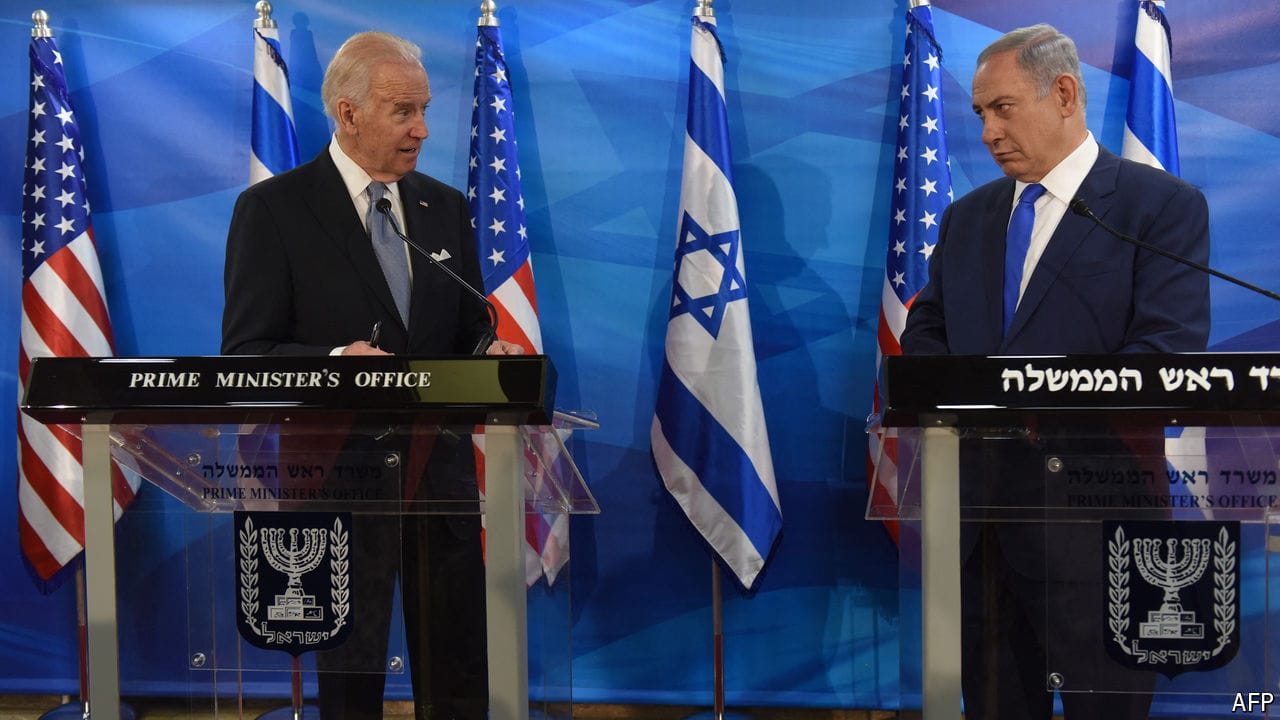

After Israel’s Killing of Seven Workers, Joe Biden Sends His Toughest Warning to Binyamin Netanyahu

Housing, painting, and fitness on the continent are not suitable for a planet

The resolution will have repercussions in Africa

Published as early as September 1843 to engage in “a serious struggle between the intelligence that presses and an unworthy and timid one that hinders our progress. “