Consider me a reconversion of the days in Ann Beattie.

I first read Beattie when I had just finished college. His first novel of 1976, “Cold Scenes of Winter”, was a reference book. momentary novel; the collections “Distortions” and “Secrets and Surprises”) traced that of his post-1960 characters, the vision came to feel a little thin. That replaced for me with the 2010 short story “Walks With Men,” which reframed that elusiveness, that opacity, broadening the author’s point of view.

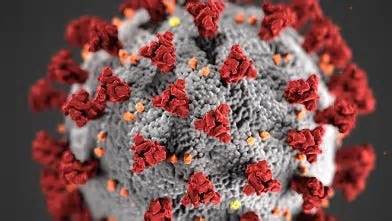

“How global it had become,” thinks one character in Beattie’s new book, “Onlookers,” which combines six long, interconnected stories set in cool Charlottesville, Virginia, a city facing a couple of accounts: COVID-19 and the aftermath. from the 2017 Unite the Right demonstration.

We know everything that happened: the Nazi flags and tiki torches, the chants of “You might not update us,” the murder of Heather Heyer at the hands of a white supremacist. Beattie, however, cares less about recreation than about effect, and rightly so. ; Fiction, even when it is a specific time and place, is not a matter of history but of nuance. It’s a mechanism of emotional truth. With “Onlookers,” this creates a bright circle as Beattie introduces and reintroduces characters moving in a kaleidoscope of narrative, from the outer edge to the middle and back again.

The opening story, “Pegasus,” sets the dynamic: A woman named Ginny, after her fiancé left for Japan for a performance gig, moves in with her father, Robbie, “an adorable, retired, medical man,” so neither of them has to triumph alone over the pandemic. It’s April 2021 and vaccines have just become available, making it a suspended moment in many ways.

First, this fiancé, Darcy – “(yes, as in Mr. Darcy),” Beattie tells us. (Its parentheses offer a brilliant metacomment. ) Then there’s the doctor’s late wife, who might or may not continue to call, and her memory, which is suspicious. Above all, there is Ginny and her emotions for the old man, on whom she now depends. “Despite her age,” Beattie writes, “in some tactics she felt closer to him than to Darcy. “

What was he saying about nuances? In Ginny’s reflections, Beattie’s intentions begin to be announced. The space is huge and well stocked; No one has to leave to get to work. There’s a dog, the lovely Blanche, perhaps my favorite canine character from late memories, and plenty of outdoor space. That it is bulky is to overlook; “As privileged as she was with Robbie,” the writer (and character) admits, “how disgusting it is to some people: Robbie would be the guy who stayed away from Lee Park at the Unite the Right rally; belonged to the club country; There was a space guardian.

It is more than a detail of character or observation; This is a central tension of the book. “Onlookers” is a name and a state of being, as, time and time again, Beattie introduces other people living remotely, either because of COVID-19 or because of their own independence, which takes many forms. In “The Bubble,” Stacey, the head nurse at an assisted living facility, returns to the domain where the demonstration erupted violently: “Meanwhile, a rainbow flag was flying from the building around the corner, and there she was, driving through the city in which it had been said, more with envy than denigration, that she existed in a bubble. But in Lee Park, that bubble had burst, as had his own protective bubble.

“Nearby”, on the other hand, reflects occasions from another perspective, with an attic overlooking the site. “The Great Gatsby” The reference is the one we assume we will understand. Rochelle, after all, is a teacher replacing a “famous guest writer” at the university who has quit his day jobs: a privilege in form.

Beattie doesn’t mean judging, or not exactly. Instead, what he seeks is a more expansive empathy. For Stacey, that means worrying about the young people who paint with her, and adds George, the shattered son of a church friend. Rochelle also discovers that she is entangled with a student for whom she buys a pair of tires.

Such generational interaction is reminiscent of Ginny and Robbie, as well as the character, Monica, who presents two stories, and her nephew, Jonah. All those other people do their best to deal with cases beyond them; Everyone takes their day jobs as productively as possible. That it is not enough, that it will never be enough, that is the challenge. who had created the opportunity had been discredited, while they were ascendants only because they had not yet become extinct?

It’s an unanswered question, the kind that fiction can explore.

Throughout “Onlookers,” Beattie isn’t afraid of politics; He has nothing intelligent to say about the former president, who haunts those pages like a demon. However, what interests him less is the debate or the diatribe than the narrative, which is so definitively resolved.

“It will be one of those days,” she observes in “Monica, Headed Home,” “when she’ll have to force herself to function. “What else can we do in a global where “everyone has their own crazy story”?There is no other option, insists “Miradores”, still to continue.

Ulin is a former e-book editor and e-book critic for The Times. His novel “Method of the Thirteen Questions” will be published in October.

Subscribe to access Site Map

Follow

MORE FROM THE TIMES