There is a contradiction between the way President Alberto Fernández is positioning themselves and some of the key measures taken through his government and, as the global coronavirus pandemic slides towards a moment or even a third fear for the general population, the point of public bellicity. The debate has increased alarmingly, as an uncontrollable epidemiological curve of Covid-19 cases. This is not worrying for the long term of Argentina’s institutional intellectual health, but it may presage an apocalyptic situation given the point of economic deterioration that has widespread in closure. long-term amid uncertainty about the existing mandatory blocking point.

President Fernandez presents himself as a moderate progressive politician who believes in the market and whose mechanism of liked functioning is discussion and consensus; it is also pragmatic: his joint control of the coronavirus pandemic, together with the mayor of the city of Buenos Aires Horacio Rodríguez Larreta and the governor of the province Axel Kicillof, has been effective and welcomed through an abundant component of the population, as evidenced by the hard notes of approval of the triumvirate. Alberto – and everyone else in that regard – knows that he owes his presidency to his vice-president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who anointed him to the head of a pan-Peronist coalition, thus shifting the still insufficient votes.

However, Cristina and Alberto love each other. Once its former staff leader, President Fernández was highly critical of the CFK after leaving government, to the point where he struck her where he injured her, noting that the notorious memorandum of agreement with Iran was potentially criminal. Alberto, the university professor, gradually discovered himself in the political arena, forging alliances within and between sectors with an organization of Peronists in Buenos Aires – he was manager of Sergio Massa’s crusade in 2017, while for years he remained close to the Grupo Clarín and its general manager Array Héctor Magnetto. He had forged a coalition for Cristina, whose votes were sought, to defeat Mauricio Macri in last year’s presidential elections, when Cristina’s unilateral decision was discovered at the top of the rankings. It was a stroke of genius, as the Frente de Todos coalition destroyed Macri in the PASO primaries, ending the fight even before it began. Although Kirchneri’s vote was surely essential in the victory, it was not entirely transparent if the other sectors of the Peronist alliance – basically those organized under the Massa Renovador Front and the “league” of fiscally conservative governors – would have lent Fernández by Kirchner. They probably would, but that wouldn’t guarantee governability, which may be just one of the reasons Cristina chose Alberto.

There is no doubt who is to blame at this stage: Alberto becomes CEO, while Cristina is the largest shareholder, with absolute veto. As for his appointments with Rodríguez Larreta, for example, President Fernández. He has already been forced to put the dogs on the mayor of the town after sections of his coalition expressed fear for their ratings in opinion polls. While the Peronist representative spoke publicly about the construction of a “social and economic council” to advise his political decisions, his intentions were explicitly closed through Cristina, ideologically opposed to the organization of classical entrepreneurs (“the G6”) and the union leaders (“CGT”) that Alberto sought to build on it. Even the restructuring of sovereign debt, led through Economy Minister Martín Guzmán, who gained almost unanimity from all political backgrounds, was only approved after a personal assembly between the young economist and the vice president.

What is worrying, and may mark a breaking point between the ruling coalition and the opposition, is the presidential bill on judicial reform. The Argentine Judiciary is a deeply corrupt and torpid bureaucratic device that has failed to satisfy the wishes of Argentine society, so the desire for reform is shared by the highest sectors. For at least more than 3 decades, the formula of justice has been a political tool used through those in power, who in turn attempt to meet the suspected challenge through those in the opposition. This is quite moderate and is an argument in favor of the plan proposed through Alberto and his Minister of Justice, Marcela Losardo. Whether or not it makes sense to expand the Supreme Court deserves to be a technical argument among jurists, however, it is transparent that when Cristina’s private lawyer, Carlos Beraldi, is on the committee that will help the president to carry out this reform, he does not respect the sanctity of the establishments. The alarms will also have to sound when Fernández de Kirchner, the acting president of the Senate, carries out a public attack on the appellate court judges who supervise instances contrary to her. If judges Leopoldo Bruglia and Pablo Bertuzzi acted in an intelligent religion in the case of the Cuadernos corruption notebooks, it does not deserve to be a matter that is explained through the Senate, which lately controls, but through the Judicial Power.

It is difficult for Alberto Fernández when he says that he is either guilty and just in his control of the State, with so many indications to the contrary, and that can lead to a break with the opposition, which will seek to oppose the leadership. for political and electoral profit. Unfortunately, among them is an economy in utter decline and a country that has been continually punished for its political incompetence.

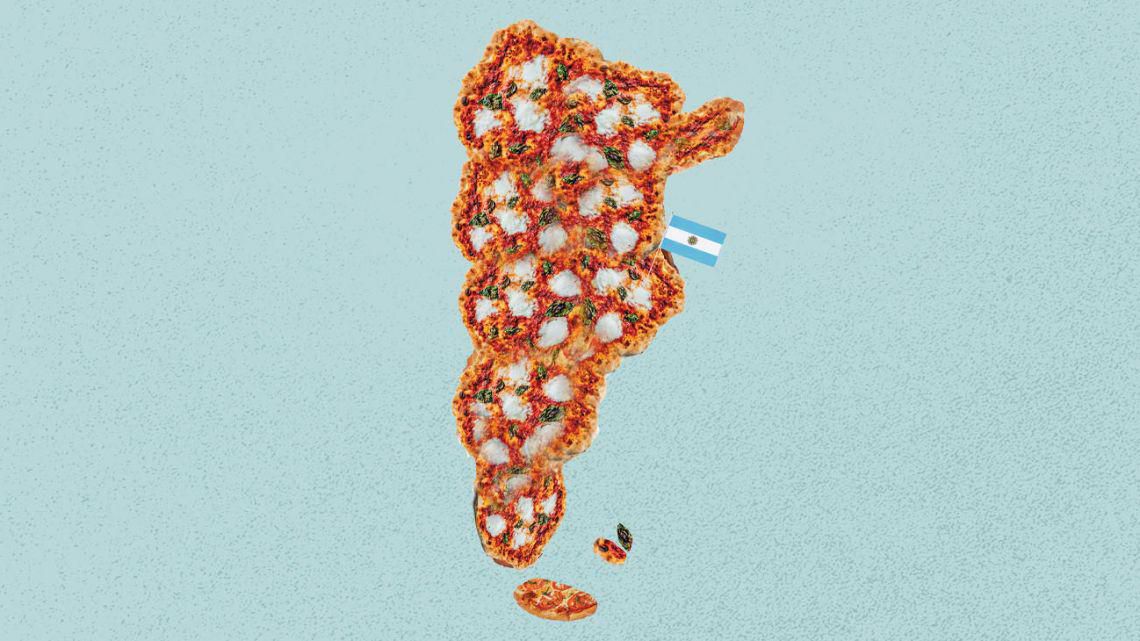

In English, when he says that anything is “in the oven”, it means that the stage is “cooking”, which is almost over. In Argentina, this translates into anything different. It’s more like saying everything’s burning completely.

This article was originally published in the Buenos Aires Times, Argentina’s only English-language newspaper.

Former Forbes expert in Latin America, with delight in markets and teams of rich lists, lately I am the virtual director of Editorial Perfil, one of the largest in Argentina.

A former Forbes expert in Latin America, with delight in richlist markets and teams, lately I am the virtual director of Editorial Perfil, one of the largest media companies in Argentina. With experience in sociology, philosophy and economics, I am a skeptic trained with a critical eye aimed at Argentina, Latin America and technology. I am also the executive director of the Buenos Aires Times, Argentina’s only English-language newspaper.