According to reports circulating in Iraq, on September 20 Secretary of State Mike Pompeo sent a transparent message to Iraqi President Barham Salih: if attacks on the U. S. embassy in Baghdad and Array coalition forces continue, the United States will close the embassy and withdraw all Americans. forces and personnel, then targeted in question in the US attack.

Pompeo is right to adopt a pragmatic technique in reaction to US attacks, but a final embassy and fleeing Iraq would be a bad decision. Previously, Pompeo closed the US consulate in Basra, Iraq, after pro-Iranian defense forces attacked him. The result was not the end of Iran’s sustained terror as opposed to the Americans, but rather its acceleration because it proved that terrorism works. If the United States withdraws from Iraq, expect the Iranians or their surrogate teams to mirror Iran’s strategy in Lebanon. Anti-American regimes or teams may also view Iraq as an inspiration for their efforts to rid their countries of the Americans. It would possibly be comforting to think that the leaders of the defense forces and the labor corps would face sustained attack after a US withdrawal. However, the US is no longer known for its perseverance and temperament in Congress would not allow the Trump administration (much less Biden) to do so.

On the contrary, if politicians such as former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki, frame chief Badr Hadi al Amiri and Asa’ib Ahl al Haq Qais Khazali general secretary continue to play a double game, a greater response style may come from Panama.

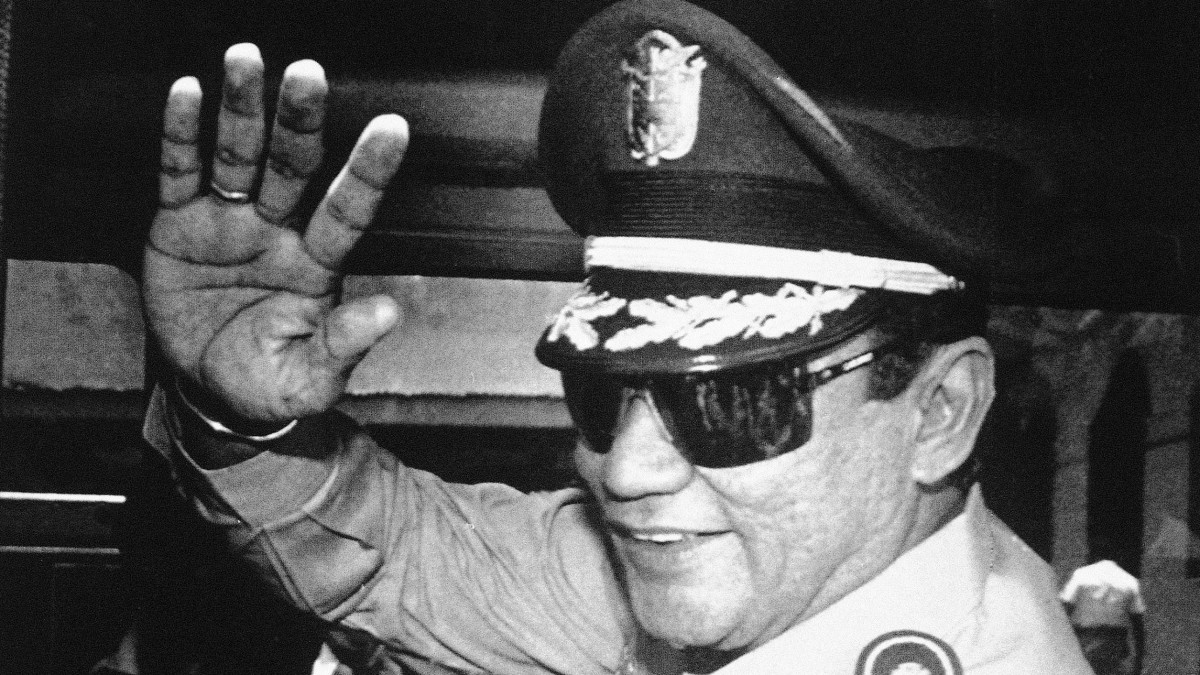

In 1989, President George H. W. Bush ordered U. S. forces to enter Panama City to arrest Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega. He doesn’t have a colorful figure. Trained at the School of the Americas, he rose through the ranks of the Panamanian army after clinging to the fortunes of 1968 coup leader Omar Torrijos. Noriega then allied himself with Washington in the Reagan-era “war on drugs” and has become a major U. S. asset. That changed, of course, after Noriega became the leader of the military junta and the two brought Panama closer to Cuba and cared more deeply about drug trafficking. Finally, on December 20, 1989, U. S. forces invaded the capital to arrest Noriega for crimes against the Americans, and two weeks later he embarked on a U. S. Air Force MC-130E. He tried and sentenced through a Miami court and spent the next 17 years in custody in the United States. He then served time in France and Panama for money laundering and murder, respectively.

In many ways, Maliki looks the most like Noriega: I climbed to the maximum sense of political scale with that of the United States, but then opposed its former sponsors, secretly at first and then much more openly. he aimed more at his non-public wallets, employing his son Ahmed as a sales agent. After falling as prime minister in the context of the rise of Islamic State in 2014, he served until 2018 as vice president, an extra-constitution post largely intended for the grazing of Benedictines or contenders to cover quotas.

The foreign chain harshly criticized the U. S. invasion of Panama and the extradition of Noriega, but privately, the maximum Panamanian gave a sigh of relief because Noriega’s challenge was over. This would never have been imaginable if Noriega had stayed. Bush, who was condemned so vehemently, was later hailed by the left and right as a wonderful sedist.

The United States does not want to launch a 1989 Operation Cause-just-scale operation, Noriega was much more rooted than Maliki and had the help (at least at first) of the Panamanian army, nor does the United States want to target Maliki. as he did to fire The leader of the Qods Qassem Soleimani Force. But holding other people accountable for attacks is a much greater option than achieving their goals through unilateral withdrawal. Maliki, of course, can remain safe from Noriega’s fate if he returns to exile. Damascus, where he lived before the dismissal of Saddam Hussein. Otherwise, Noriega’s Miami cell phone is empty.

As for Amiri and Khazali: they are aware of their own declining legitimacy. On September 13, 2020, the great Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani stated that “the parliamentary elections scheduled for next year are of great importance” and encouraged Iraqis to participate “in general” This contradicts their pre-2018 elections in which he compared the elections to a glass of water in which one may decide to drink, an analogy that Iraqis believe is to blame for the fall in participation , while defense force leaders have continued to attract their help to the polls.

In short, next year’s elections will largely verify what Amiri and Khazali need not admit: Iraqis need a better life, and they need unwavering politicians in the face of baghdad’s government than they do before Tehran. become less relevant. In fact, Iraqis realize that while hashd al-shaabi was at the forefront of fighting opposed to Islamic State, their own teams were more interested in looting than fighting, as were volunteers who responded to Sistani’s call. The United States may simply target them, but it will have to do so in a way that does not allow them to wrap themselves in an Iraqi nationalist flag after spending much of their careers denigrating it.

Pompeo is right that the United States deserves to protect its personnel, and is right to convey to the Iraqi leadership the seriousness of American intent. However, a withdrawal from Iraq would not meet U. S. strategic objectives or stabilize Iraq. As the elder Bush in Panama demonstrated three decades ago, the most productive way to fight cancer is to use a scalpel instead of an axe.

Michael Rubin is a contributor to the Confidential Beltway Blog at the Washington Examiner, a resident researcher at the American Enterprise Institute and a former Pentagon official.