By Elena Rodina, Associate Researcher of Europe and Central Asia August 6, 2020 3:26 PM EDT

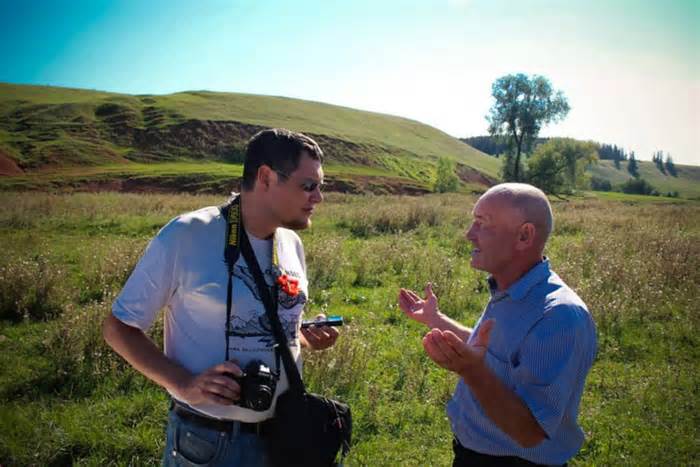

Vladimir Sevrinovsky is a Moscow-based freelance journalist and documentary photographer who has covered social and cultural issues in Russia for independent news Meduza, independent weekly Russkii Reporter and Kavkaz.Realii, a regional service of the television channel funded through U.S. Congress Radio. Free Europe / Radio Liberty, among others.

Sevrinovsky’s latest recent project to report on the North Caucasus region in Russia on the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In March, he was one of the first hounds in Russia to monitor the closure of Pandemic-related Chechnya, whose leader Ramzan Kadyrov has a history of human rights and press freedom violations and was blacklisted by the U.S. government for human rights violations. Sevrinovsky also analysed the physical fitness crises caused by the pandemic in the republics of Dagestan and Karachay-Cherkessia, where the number of cases reported through local government particularly decreased than actual figures, according to Sevrinovsky’s data and research.

Sevrinovsky spoke by phone with CPJ in June and July about its reports on the COVID-19 pandemic in the north Caucasus. Their answers were changed for reasons of duration and clarity.

How has the pandemic affected your journalistic work?

I stopped doing all the journalistic paintings not related to COVID. I was able to report on a complete closure in Chechnya, which was an exclusive experience. What distinguishes Chechnya from the rest of the North Caucasus is the incredibly strict exercise through local authorities. When the coronavirus arrived there, the cause was the death of the first COVID user, which occurred in early march in the last week of March, Kadyrov literally closed the republic immediately. The resolution to close all public spaces was taken on March 23, and on the same day, everything was closed with unprecedented speed.

Can you describe how COVID-19 closure occurred in Chechnya?

My colleague and I were at a café that day. Several men in khaki uniforms came here while we were eating and said it was closed, so we had to leave. Only two places to eat were allowed to remain open until the night of March 23: Paris, believed to belong to Kadyrov’s daughter, and a place to eat located in the city of Grozny [luxury hotel]. The same thing happened regarding Kadyrov’s order to wear masks and gloves in public: we were going to an interview in a taxi, and on the way, no mask didn’t even mention, on the way home, the driving force of the taxi is no longer easy to put on. on the mask and gloves. The order issued and implemented while conducting this interview.

Were you stressed by the local government while the closure was running in Chechnya?

I am fortunate not to be interfered, however, I understood that I was in a privileged position as a journalist from Chechnya outdoors. I had relative freedom of movement, I can go through the center and walk. But when I spoke to my Chechen friends, they told me that, unlike me, their movements were very limited. After leaving Chechnya on April 3rd, I told him that there were days when the house was totally forbidden, even to move into the grocery store.

[On 15 May, Kadyrov announced that the “quarantine exit” from Chechnya would take position in 3 stages, the first from 15 May, the time on 27 May and the 3rd on 15 June.]

You covered COVID-19 in neighboring Dagestan after leaving Chechnya. Like that other guy from Chechnya?

Unlike Chechnya, the Dagestan government did not regulate anything for long after the start of the pandemic in the country. The mosques remained open and thousands of people came to pray even in April. People continued to hold giant weddings and funerals, gathering in giant crowds. In the absence of adequate government action, this has in fact led to catastrophic consequences.

Why do you think other people have ignored COVID-19 for so long in Dagestan?

Dagestan’s government has become a victim of its own lies: while enthusiastically advising others to be careful during the pandemic, others did not believe them. The other people of Dagestan don’t accept much as true with local government. At the same time, when they looked at statistics from the republic’s inconsistent headquarters, they found that the mortality rate in Dagestan remained very low, a user consistent with the day. Later, it was discovered that the statistics did not reflect the actual image. As a result, the Daguestanis paid no attention to COVID-19 and continued to attend mass events. In addition, due to artificially deflated statistics, they did not unload enough drugs from the federal center, as their distribution was discovered in the official statistics.

When did other people realize, however, the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic in Dagestan?

The moment the pandemic scale became transparent was when others began to become seriously ill and die in the villages. While dagestan’s capital, Makhatchkala, is a giant city where it is difficult to know how many other people have health problems or die, in the small mountain villages of Dagestan, it is to hide it. Local media have begun conducting their own investigations, comparing official COVID statistics with the number of other people’s cases registered as affected by network pneumonia. And finally, on May 16, Dagestan’s Health Minister, Dzhamaludin Gadzhiibragimov, in a video interview on the Instagram feed of Dagestan journalist and blogger Ruslan Kurbanov, said that “13,697 others had COVID-19 and pneumonia,” while only 3280 were inflamed COVID-19. other people have been known in official statistics. He also claimed that on 16 May, at least 40 doctors from Dagestan were killed by COVID, while the official number of COVID deaths in the republic in total at the time was 27. This has temporarily become a national sensation.

The most impressive thing about Dagestan was that once other people understood the scale of the problem, they showed an ability to organize. In villages, local jamaats [village citizen communities and other indigenous people with strong links to the village] established quarantine regimes at the local communal level, organized communication, food purchase and coordination of loose drug delivery through WhatsApp. This effectiveness of the base contrasted markedly with the absolute impotence of the authorities.

Has the government interfered with your journalistic work?

Not actively, but they weren’t willing to cooperate either. When I wrote a report for Meduza and asked the Department of Health to provide me with statistics for other inflamed people with network pneumonia, that’s not the case. When I requested to provide my access to hospitals and an emergency medical team, the branch did not. The local government also hid the actual number of other people inflamed with the crown for as long as possible. But I cannot say whether it was intentional, or simply the lack of preparation: in Dagestan, the coronavirus detection rate decreases four to five times that of Russia as a whole.

The biggest challenge for me was the checkpoints, which at one point sprang from Dagestan to control the spread of the coronavirus. When I went to the village of Gergebil, I was arrested at one of them. I had a press license, so I was allowed to continue, but my taxi driving force didn’t have one, so I didn’t have one. I had to hitchhike to get to my destination.

[The CPJ contacted the Government Apparatus of the Russian Federation and the Ministry of Health of Dagestan for comments on COVID-19 statistics and detection rates in Dagestan. On 30 July, the CPJ informed through the Apparatus of the Government of the Russian Federation that the request for comments had been won, evaluated and sent to the Russian Ministry of Health for review. The CPJ did not get any reaction from Dagestan’s Ministry of Health.]

What was your experience covering COVID-19 in Karachay-Cherkessia?

This is the most difficult component in terms of my interaction with local government. In Karachay, the government only recorded deaths as caused by COVID when the deceased had no chronic illness and when there was a widespread invasion. This has led to significant deflation of statistics. The local government was afraid of being denounced and tried to save you any report right on the stage. Although they have no influence against me, a Moscow journalist, they pressured the local media and the doctors who courageously told the fact on stage with COVID.

What kind of strain is that? What local media are you targeting?

Currently, two independent local media outlets, the Cherny Kub YouTube channel and Instagram’s corporate policy Politika 09, are being investigated by the corrupt local government for “spreading false information.” Both published interviews with Leila Batchaeva, head of the epidemiology branch of Karachay District Central Hospital, who said the COVID statistics she had provided for her district had artificially deflated about seven times once they were discharged to the republic level. Array After that, Batchaeva itself called for asking itself in the Center to counter extremism. Three doctors who agreed to be interviewed for the article I wrote for Meduza are now being harassed by the head of their hospital, who threatens to fire them for talking to me.

[Since the interview, Batchaeva has been forced to resign and, in a new interview with Sevrinovsky, said the hospital chief and local police had pursued her for speaking to the press. The CPJ contacted the Russian and Karachay-Cherkessia fitness ministries and Karachay District Central Hospital to comment on the alleged deflation of coronavirus statistics in the republic and the strain that would oppose Batchaeva, but did not get a response.]

What are you doing, how’s it working?

When I fly, I sit at the window. For local transportation, I use taxis and have my own masks, respirators and medical glasses every time I go to the hospital. Some hospitals have provided me with protective equipment, but not all.

How do you handle and respond to incorrect information about the virus?

The main incorrect information I’m struggling with is the one that comes from the state, and my main goal is to disclose forgeries from local authorities. At the same time, at the regional level, other people are filing a massive demand, a “thirst” for truthful reports, and I’m looking to meet their expectations. So while it’s very stressful to cover COVID, this incredibly strong other people inspire me and allow me to continue.

The CPJ protection notice for hounds covering the coronavirus outbreak will be available in English, Russian and more than 35 other languages.

Elena Rodina of Kazan, Russia, worked as a Moscow-based socio-political correspondent for Ogoniok, one of Russia’s oldest weekly magazines, and Esquire Russia. His journalism and studies have been published in Caucasus Survey, Digital Ethics, Time Out Chicago, Newcity, Media and Communication and Zeitschrift fur Slavische Philologie, among others. Rodina holds a doctorate in communication from Northwestern University and a master’s degree in Russian, Eastern and Eurasian studies from the University of Oregon, in addition to her bachelor’s degree in Roman-German philology from Kazan Federal University (formerly the State) of Russia.