Read our news and about COVID-19.

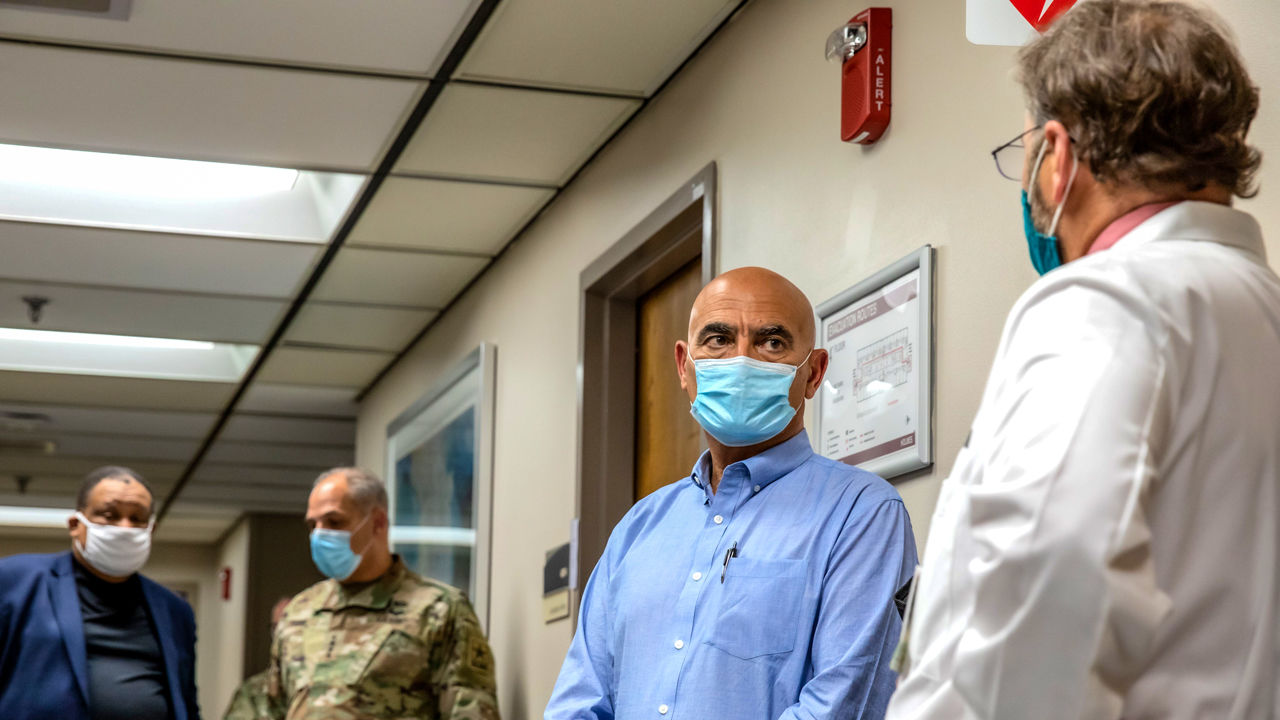

Operation Warp Speed leaders Moncef Slaoui (second right) and General Gustave Perna (second from left) meet with Cincinnati doctors Carl Fichtenbaum (far right) and O’dell Moreno Owens (far left) to make a stopover at one of the sites for modern’s COVID-19 candidate vaccine effectiveness trial.

Science COVID-19 reports are supported by the Pulitzer Center and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

CINCINNATI – A University of Cincinnati (UC) hospital is located on a street named after Albert Sabin, who developed a polio vaccine that helped eliminate the previously feared global disease to the fullest. participates in U. S. efforts to locate a vaccine opposed to COVID-19. Last week, on September 25, the leaders of Operation Warp Speed – the Trump administration’s $10 billion vision program – came here from Washington, D. C. , for a tour. Upon learning that the hospital had recruited about 130 participants in the Phase III multisite efficacy trial of an experimental vaccine in 3 weeks, the first question posed by Warp Speed’s chief scientific officer, Moncef Slaoui, was: “Do you have intelligent representation of populations?”

This was a recent scale to review vaccine sites and plants through Slaoui and its co-director of Warp Speed, General Gustave Perna. (GSK), wore casual trousers, an open-necked blouse and penny loafers without socks, with the aim of making others feel comfortable during the tour, encouraging them to talk about uncomfortable topics, including taboo: race, politics, regulations and risks. Perna had small conversations with clinical staff, but largely remained alone.

The national efficacy trial, which compares a COVID-19 vaccine manufactured through Moderna with a placebo, first struggled to recruit black and Latino participants, in part because they hire study organizations representing three-quarters of the nearly 100 verification sites. had few contacts with those communities. But the UC site and others in colleges, a component of the COVID-19 Prevention Testing Network (CoVPN) organized through the U. S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). U. S. , They have a long history of working with minority communities to recruit clinical trials Doctors who run this UC site explained to Slaoui that about a component of the participants enrolled in the Moderna trial are black or Latino, which largely corresponds to the distribution of the city (according to the U. S. Census Bureau). U. S. , Cincinnati’s 300,000 citizens are 50% white, 43% African-American/black, and nearly 4% Hispanic/Latino).

Modern tracks and makes public the demographics of registered participants week after week. In the week leading up to the start of UC registration for the 30,000-person test, participants recruited from the other sites were 67% white and only 9% black/African -American and 17% Latino/Hispanic. Carl Fichtenbaum, principal co-investigator on the UC site, during a call to the convention on September 1 with other CoVPN researchers, NIAID Director Anthony Fauci and General Surgeon Jerome Adams warned that sites restrict the number of white participants they can simply recruit. “I asked the question, “What is the most important thing, reach 30,000 as temporarily as you can imagine or make the essay representative of our country and the pandemic?”, remember Fichtenbaum. On September 21, those enrolled on all Moderna verification sites were 42% Latino/Hispanic, 30% African American/black and 7% white. Together, on the scale day of Warp Speed leaders at UC, 31% or i the 27,232 participants in modern’s essay came here from “several communities. “

The UC team says their recipe for successful minority participation is to rely on community check recruiters, component announcements for those groups, and Hispanics who are part of the clinical team. “We sense the history of Cincinnati and the history of our city unrest and lack of inclusion,” Fichtenbaum says. The hospital, he says, not only has “unattended” but “rooted” roots for a long time.

Margaret Powers-Fletcher, lead co-investigator at the UC vaccination site, noted that many misunderstandings revolve around the Modern vaccine At one end, Powers-Fletcher was asked if the vaccine had been funded through Bill Gates as a microchip attempt by the population but, more generally, other people need to know Modern’s vaccination technology. The vaccine includes messenger RNA (mRNA), which encodes the surface protein of the virus guilty of COVID-19. Explain that this “opens the door” to a deeper conversation. ,” he says. This gives us the opportunity not only to communicate what mSA is, but also to dispel other vaccine-related myths. “

Slaoui adds that the diversity of trials will generate a “commitment and confidence” that will result in a wider use of a COVID-19 vaccine that will in the end be approved. “The vaccine that stays on the shelves, if other people don’t settle for it is useless,” he says.

O’dell Moreno Owens, a black doctor who runs the Cincinnati-based nonprofit Interact for Health joined the tour and raised several provocative concerns: the first is that Warp Speed now supports efficacy trials of 4 other COVID-19 vaccines, and a weeks ago, an overseas trial of a COVID-19 vaccine candidate manufactured through AstraZeneca and Oxford University was suspended after it occurred a serious effect on a recipient (UK and Brazilian regulators have decided that this is not vaccine-related and that resumption of trials is legal, but the US has not yet done the same). “The domino effect on the net was: Array, I told you,” Owens says. be a big problem. “

“It’s a real challenge to talk about these vaccines and their protection and inspire others to use them. It is aggravated by all lighting fixtures,” Slaoui replies. “Unfortunately, the world we live in, this time and all the policies around it exacerbate the anxiety that exists. “

Jaasiel Chapman, the liaison officer of the city’s black network trial network, says it’s to escape the division. “People feel that this pandemic has become so politicized and that other people need to win the election, rather than save our lives. anything we’ve spread on the net, ” he says. ” They feel the government has never cared about us before, so now they’re just looking for a vaccine to kill us. So it was hard, doubts on the net.

Just as Slaoui would like to circumvent politics, they also overshadowed him. On September 25, the day of the UC tour, he posted a video criticizing Senator Elizabeth Warren (D – MA) for suggesting a Senate hearing in which she had a conflict of interest due to her investments in corporations. that make COVID-19 vaccines. . “He doesn’t know me personally and he publicly accuses me of being greedy, of being corrupt and of doing this to enrich myself,” said Slaoui, who has been unusually appointed to co-lead Warp Speed as a government contractor, not a federal employee. . Sitting at a table with a Warp Speed logo behind him, Slaoui noted that he had done everything he could to separate his finances from the vaccination effort, only keeping the GSK inventory because it was his retirement savings. “I cannot take advantage of this role and my commitment is to help other Americans fight this epidemic. It is mathematically more unlikely that I will get rich, ”he said. “I did not hesitate to sign up for the position even though I am a registered Democrat, because this pandemic is bigger than any of us. It’s bigger than me and it’s bigger than you. Please avoid distracting me and me and Operation Warp Speed.

Warp Speed’s main concern about vaccines, as Slaoui noted several times during the UC stopover, was protection, Cincinnati physician James Powell, who runs an assignment for the National Medical Association, which represents doctors and black patients, to raise awareness of participation in clinical trials shared the concern. He told Slaoui that he was involved in protection when a vaccine went from a 30,000-person trial to millions of people in the real world.

Slaoui says that to better balance potential benefits and threats, vaccines will first be sent to others at maximum risk of serious illness. He also approved an initiative through the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which the Trump administration reportedly challenged. to load a protective measure on vaccine approvals that can also slow down the process Independent forums that monitor vaccine trials review knowledge and if they see a sign of effectiveness or effects of harmful aspects, they may propose an early termination of a trial An early sign of effectiveness, in turn, can also lead brands to look for what is called an Emergency Use Authorization (USA).

There is widespread fear that politics can only influence the delivery of an AMERICAN vaccine, as critics say President Donald Trump and his allies have pushed too aggressively for similar approvals for two unscheduled COVID-19 treatments, hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma. Other management clinical advisers have said a vaccine candidate is highly unlikely to be safe and effective in October, ahead of the November 3 presidential election, Trump has continually introduced the idea. FDA officials insisted that the policy would not influence their decisions. , and recently proposed a regulation that would not become an UCA until at least 2 months after the last player in a test was fully vaccinated.

Towards the end of the visit, Powell asked how many black researchers were involved in the Warp Speed trials and how many sites were in traditionally black schools and universities (HBCU).

“He is, “It’s not enough, ” says Slaoui. (Two HBCU presidents recently joined the COVID-19 vaccination pathways and asked their academics and teachers to participate, but the call also produced negative reactions. )

Upon saying goodbye, Slaoui praises the other people involved in COVID-19 vaccine trials. “It’s a very generous act. ” And he regrets what he called the “involuntary result of communication on the political aspect of things,” which he said “frightened vaccines. “

“The way to counter this is to be transparent and explain,” Slaoui says. “And we want everyone’s help. Thank you so much for being here. “

Jon is editor of Science.

More sieve