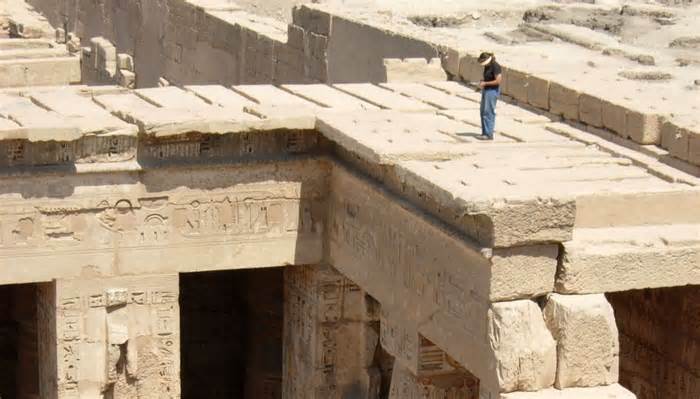

For a hundred years, researchers from the University of Chicago have traveled to the ancient Egyptian temple complex of Medinet Habu, near the banks of the Nile. They take photographs, draw each and every hieroglyph and landform: thousands of them. Now they are racing against time to keep the story going, while global warming and groundwater seepage from neighboring farms threaten to destroy it. Christina Di Cerbo copies here an inscription on the roof of Médinet Habou.

Ray Johnson

Standing near the banks of the Nile for 3,000 years, with its colossal stones boiling in heat reaching 122 degrees Fahrenheit, this ancient temple located on a desert plain, uninhabited for much of its history by the slithering of a viper or snake. A scorpion glide.

On its walls, Ramses III looms above kneeling foes, one royal arm raised in preparation to smite his enemies. There is a gruesome inventory chiseled into the sandstone of the severed hands and genitalia of the defeated.

For a hundred years, Egyptologists, illustrators, and photographers from the University of Chicago have visited this extraordinarily well-preserved Egyptian temple complex called Medinet Habu, replete with cameras, pens, and, at first, rickety wooden staircases. His project is to record for history the thousands of ancient inscriptions and engravings in stone.

Now, they are racing to record and preserve the ancient history of this place as climate change and seeping groundwater from neighboring farms threaten to erase it.

Artist Keli Alberts making a sketch of engravings at Medinet Habu in Egypt.

Ray Johnson

The researchers live together for months in Luxor, in a place nicknamed “Chicago House,” just like their predecessors, going through wars, infighting, and occasional cholera outbreaks.

“There are quiet moments when you realize I’m sitting here in a temple that’s over 3,000 years old and I’m reading inscriptions that very few people have read or can read,” says Egyptologist Brett McClain, who oversees the study operation at the Chicago House for the University’s Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures.

Brett McClain, manager of the Chicago House in Luxor, outdoors the 3,000-year-old Medinet Habu complex west of the Nile.

Brett McClain

James Henry Breasted was the University of Chicago professor who founded Chicago House in Egypt in 1924. A real-life Indiana Jones, this son of a Rockford hardware merchant began his education as a theology student but distrusted some translations of the Bible and decided he wanted to see for himself the world described in its pages.

Breasted was suffering from “severe bouts of indigestion” and was told by his doctor that if he went abroad, it would have to be with a doctor or, at least, his wife. So he brought his wife Frances and their 8-year-old son, Charles, traveling to the Middle East with a civil engineer and a photographer.

“I can’t walk. . . to my office. . . But I will go to Egypt if I go on a stretcher!” he said in 1905.

James Henry Breasted, who founded Chicago House in Egypt in 1924, was under his doctor’s orders not to travel without a physician — or at least not without assistance. So he traveled with his wife Frances and son Charles, seen here at Abu Simbel in Southern Egypt in 1906.

University of Chicago Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures

Breasted’s travels eventually saw him travel by boat, biplane, canoe, and donkey. One day he was shipwrecked on the Nile.

In Egypt, he and his fellow explorers wove the narrowest passages of temples, taking photographs in “sweltering darkness,” his son Charles Breasted wrote in his 1943 book “Pioneer of the Past. “

Outside some other temple, the team attacked through “swarms of mosquitoes,” scorpions and tarantulas that fell on them from tree branches.

At a time when Americans were looking to the future, Breasted preached the importance of preserving the ancient world.

“It is frightful to see those priceless monuments of the beyond man perish year after year,” he said in a 1928 speech as president of the American Historical Association. “The monuments of the ancient East demand a new crusade. “

Medinet Habu is a walled complex that extends four blocks from Chicago. To the west lie the ocher Theban hills and to the east the Nile. The centerpiece of the complex is the mortuary temple of Ramses III, a pharaoh who ruled for 31 years, fighting off several invading armies. Perhaps best known for repelling the “Sea People,” invaders of the Mediterranean Sea, he himself led the battle, drawing his bow along with his archers, according to historians.

Armies of scribes celebrated their victories. They carved relief scenes and hieroglyphics from sandstone and depicted festivals, ritual offerings, and gods.

The fortified walls of Medinet Habu house a temple dedicated to Amun, “king of the gods,” as well as priests’ quarters, barracks, stables, and ponds.

The palace of Ramesses was also located there. History does not record the number of them, but it is certain that he had many wives and children. Jealousy inflamed the harem, Breasted wrote in his 1905 e-book “A History of Egypt. “Tiy, one of the wives, plotted to kill Ramesses. in an attempt to position his son on the throne. Researchers discovered supporting evidence through a recent CT scan that showed a cut on Ramses’ mummified neck and a missing toe.

“Someone took an axe and put it through his foot, pinning his foot to the floor, then his throat was slit with a knife,” McClain says of Ramses’ killing in 1155 B.C.

Papyrus scrolls detail the trial and the gruesome fate of the 32 conspirators, though there is no record of what happened to Tiy.

“There was some flogging to get them to talk,” says Emily Teeter, a recently retired U. of C. Egyptologist who is writing a book about Chicago House.

The culprits were “allowed to commit suicide,” though some had their noses and ears cut off as punishment, Breasted wrote.

Dressed in a tweed suit and high leather boots, Breasted scoured the Nile valley in search of a place to set up. He chose Medinet Habu because, as far as he could tell, no one else had made a detailed and accurate record of the inscriptions there.

Not only was Breasted an adventurer, but he was also exceptionally clever at convincing others to join his crusade, or at least pay for it. Much of the initial investment came from a privileged friend: John D. Rockefeller Jr.

The original Chicago space was built of dust bricks, with no running water or litter boxes for the bathrooms. The bedposts were submerged in kerosene cans “because scorpions can move slowly between the sheets and sting you when you walk in,” McClain says.

The Chicago house in the 1920s.

University of Chicago Epigraphic Survey

During the early years, a handful of Egyptologists, illustrators and photographers lived in the Chicago House with an Egyptian butler and other servants and workers. Then, as now, the team spent six months a year living and working together. Disputes were not unusual over such trivial topics as who sat at which table.

“Three pathological cases. . . they kept me quite busy and raised the question of whether I could get a position as superintendent of an insane asylum,” Breasted, back in Chicago, wrote in 1927 to Harold Nelson, the first director of Chicago House.

James Henry Breasted and researchers examine a large statue of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel in the early 20th century. Breasted’s wife, Frances, and the couple’s son, Charles, are seen on the right, at the foot of a staircase.

University of Chicago Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures

At one point, police were called to investigate a Chicago House photographer who had roughed up some locals because he didn’t like the way they treated their animals, Teeter writes in her book.

In 1956, during the Suez Crisis, Israeli forces surged across Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The American government advised U.S. citizens to leave Egypt. The Chicago House team chose to stay even as bombs fell and anti-aircraft shells burst over Luxor.

“Recent events have left us speechless, and, like the rest of the country, we are shocked by the Anglo-French-Israeli aggression against Egypt and astonished at the stupidity of those who organized this enterprise,” wrote George Hughes, director of Chicago House, November 1956.

Yarko Kobylecky taking photographs of hieroglyphs in a narrow cavity at Medinet Habu.

Amanda Tétreault

The paintings at Medinet Habu begin with the taking of a photograph. An artist, in the published photo and sculpture, then traces the photo with pencil, in an effort to capture the main points that the camera might not clarify.

“There is no finer instrument than the human eye for doing this,” Teeter says.

Heads bow, examining the comic and the sculpture. Egyptologists recommend changes. Where the stone collapsed and fell, experts look for what was likely there. The layer is inked, the photo is faded. A plan is drawn up. Then other corrections.

Only when everyone will send the final pencil drawing to their editor.

Those drawings — bound in nine volumes, each measuring about two feet by one and a half feet — can be found in the U. of C.’s Elizabeth Morse Genius Reading Room.

Today, after a hundred years, Medinet Habu’s paintings are only two-thirds complete, McClain says.

Almost every square inch of Medinet’s walls is decorated with some sort of sculpture, from a matchstick-sized horned viper to the monumental sculptures of Ramses that stand about 15 feet tall.

Researchers try to record these sculptures for posterity. At first, they used bulky, fixed cameras, now supplemented by new virtual opposite numbers and three-dimensional scanning. Otherwise, the paintings remain unchanged. Scientists continue to carry out their responsibilities in confined spaces, in the middle of sandstorms, running for hours at a time on ladders or scaffolding.

Margaret De Jong and Brett McClain in paintings at Medinet Habu. Digital cameras and on-site generation are now used, but many of the paintings are still done by hand on stairs.

Ray Johnson

Paintings are not without risk. One day, an Egyptologist broke his heel when he fell from a ladder. Nelson stumbled one day in the ruins, breaking his arm and tearing a muscle. In the mid-1920s, a photographer died of liver disease after drinking water from the Nile. .

At Yde Park, the superstar of ancient Egyptian history towers above everything else at the university’s Museum of Ancient Cultures: Standing 17 feet 2 inches tall, it’s made of red quartzite carved with stone tools. The statue of King Tut is so heavy that the metal beams underneath it to prevent it from crushing the ground.

“When you think about the hours of painting [to sculpt it], it’s certainly spectacular,” Teeter says.

The statue, dated as having been created around 1325 B.C., was one of two that once flanked a doorway near Medinet Habu. In 1933, the Egyptian government took one. The other ended up on a ship bound for America.

“It was perfectly legal at the time,” McClain says. In those days, when you were given permission to dig, you shared the findings. »

Times have changed.

This 17-foot-tall statue of Tutankhamun, which dates to about 1325 B.C., was one of two King Tut statues excavated at Medinet Habu in 1930 and is now on display at the University of Chicago’s Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures. The other is in Cairo, Egypt.

Anthony Vazquez/Sun-Times

The focus at Medinet Habu now is about preserving history in its original setting.

While climate change is a long-term concern, there is now a more urgent one.

To the west of the temple complex, the hills are treeless and dusty. To the east stretches a green landscape thanks to agriculture made imaginable thanks to the finishing touch of the Aswan Grand Dam in 1970. But what has been smart for crops can be ruinous. for old stones, which absorb water like a sponge.

The pain is evident in a Medinet Habu sandstone block first photographed in 1994 and in 2022, after having been buried for years.

A block from Medinet Habu photographed in 1994.

Yarko Kobylečky

The same block in 2022, now removed from the ground.

Brett McClain

Due to the accumulation of water, sandstone that has existed for thousands of years is now disintegrating and re-deserting.

“That’s why we do what we do,” McClain says. “Physical monuments may not survive, but to the extent that we do, we want their ancient data to be preserved for the future.

“We’re far from done,” he says, McClain. La number of monuments in Egypt is so vast that it is almost inexhaustible.