This story was originally published through Undark and reproduced here as a component of climate desk collaboration.

The voice of Luz Angela Uriana trembled when she described the Covid-19 scenario in her region. “We’re afraid, ” he said in a phone call. “There are many cases in our nearby village.” Concerned specifically for her son, who has lung problems, she added that she and others “want Cerrejón to avoid their activities while this disease is rampant. And the other people who paint in the mine come from other places, it’s also a risk.” Cerrejón doesn’t protect us.

Uriana is an activist and member of the Wayuu, an indigenous people in northern Colombia and Venezuela. An organization of them called on the United Nations to interfere in its fight in opposition to the owners of one of the largest coal mines in the world, called Cerrejón, on the Guajira peninsula, near the border with Venezuela, and right in the middle of the ancestral Wayuu. Territory. The region has been devastated by poverty, drought and, since the advent of large-scale production in Cerrejón, critics say, destructive pollution.

Now, while Covid-19’s global pandemic weighs on Colombia, the Wayuu face a new risk, a risk that Uriana and others say are exponentially exacerbated through ubiquitous coal dust and drought. They called on many UN officials, adding to the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Environment, to suspend some of Cerrejón’s mining activities. “Covid-19’s emergency aggravates the scenario itself,” said Monica Feria-Tinta, a UK lawyer at law firm Twenty Essex, concerned about Wayuu’s appeal. According to the data, he says, air pollutants are making the stage worse. Lack of water to wash your hands also makes it difficult to prevent the spread of disease.

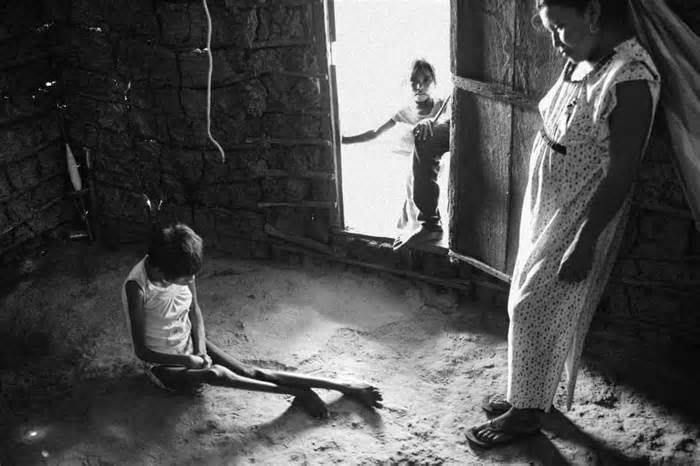

A young Wayuu, Monica, represented here at the age of 26, sits on the ground in her space near the coal railway in 2016. Her mother Rita (right) and younger sister (in the middle) cared for Monica because she was malnourished and mentally ill. fitness problems, until his death in 2018. The lack of food and drinking water, in addition to the pollutants of coal dust from the Cerrejón mine, is destroying the way indigenous peoples in the La Guajira region are destroying the way of life. Nicolo Filippo Rosso

“That is the reason that pushed the Wayuu to appeal to the U.N.”, she added. “It is a matter of survival — of not being wiped out.”

The battle pits members of the Wayuu — the largest Indigenous group in Colombia — against the owners of one of the largest coal mines in the world, and at over 270 square miles, the largest open-pit coal mine in all of Latin America. The mine — owned jointly by global giants BHP (Britain-Australia), Anglo American (South Africa), and Glencore (Britain) — employs more than as 5,800 people, according to the facility’s own figures, and it has done much to support education and health services in the region over the years. But conflict with the local community, arising from both the pollution as well as infrastructure decisions that, the Wayuu say, have favored Cerrejón’s water needs over their own, have become more pitched with the arrival of Covid-19.

Cerrejón, which strongly demanded water situations and environmental loads, in the past slowed its operations in Colombia’s national quarantine, but resumed general operations in May. The appeal on behalf of the Wayuu to human rights officials at the UN was filed last month.

The Pinilla coal mine at the Cerrejón mine. From this 330-foot-deep well, 400,000 tons of coal are mined per month. Daily explosions damage the design of nearby homes and spread coal dust. Respiratory diseases are not unusual in those living near the mine. Nicolo Filippo Rosso

It is known whether the United Nations will have the right to interfere in the case. But with giant percentages of Wayuu suffering from fitness and malnutrition problems, network activists, adding Uriana, say the persistent threat of Covid-19 infections amid so many other environmental sludes is too much a threat.

“We breathe polluted air 24 hours a day,” Uriana said. With coal everywhere, he says, “we eat it, we sleep with it.”

The Beacon Other options

Ask your climatologist if Grist is for you. See our privacy policy

The La Guajira region now has 1,578 cases of Covid-19, and rates are emerging rapidly. Eighty-one more people with Covid-19 died in La Guajira. Speaking to Colombian media earlier this month, Nemesio Roys Garzón, the governor of the region, appealed to federal officials in Bogota. “Everything has been done with the own resources of the government and those of the mayors,” he said. “For this reason, we can’t keep waiting, because we’re putting Los Guajiros’ life at risk.”

The link between air pollutants and a greater threat of death by Covid-19 has been analyzed empirically. Several studies, adding one through Harvard University researchers and published as a pre-impression in April, prior to peer review, advised that others living in U.S. spaces with high degrees of exposure to air pollutants from automobiles, refineries and power plants, especially in the microscopic air Debris known as PM2.5 would possibly provide a greater threat of death from Covid-19 infection than other people living in spaces where the air is relatively cleaner. It is also widely accepted that other people with pre-existing physical condition problems, which add lung and central diseases, are most at risk of pandemics.

The Wayuu, on the other hand, are already known for their poverty, with high rates of malnutrition and disease. About 53% of the other million people in La Guajira live in poverty, and the rate reaches more than 80% in rural areas. Almost 30% of other people over the age of 15 are illiterate, the rate in the country. In a December ruling, Colombia’s Constitutional Court cited clinical records that appeared that many Wayuu suffered from a multitude of diseases, including bronchial asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bacterial pneumonia, decreased respiratory tract infections, and acute obstructive laryngitis.

The other people in the network prepare and make a percentage of the food provided through a local NGO founded in Bogota, whose objective is solidarity among the Wayuu. Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Just how much of this can be attributed to mining activity is a matter of fierce debate. A comprehensive environmental study by the Institute for Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz), a non-governmental organization based in Bogotá, for example, found high levels of heavy metal contamination in local soil and water samples, as well as high levels of airborne particulate matter around the area of Cerrejón. While the study determined that the mine was a contributor to local pollution and should be better regulated, however, it could not conclusively link the high contamination levels to mining activities, and acknowledged that industrial, agricultural, and urban activities in the region were also contributing to pollution. In a response to the report, included as an annex, Cerrejón officials called into question, among other things, the group’s testing methodologies and equipment.

However, the mine censused several times, adding in December, when the Constitutional Court discovered that mining directly affected the fitness of indigenous peoples and the surrounding environment. The court also cited studies conducted through the University of Colombia and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, which revealed that the air around Cerrejón was measurably infected with coal dust and that blood tests of the local population had maximum concentrations of various metals.

As reported through El Specteator, Colombia’s oldest newspaper, the court ordered Cerrejón “to the degrees of components emitted through its air-polluting activities; to the blank net houses of all coal dust, a waste that is a component of mining; Reduce on-site noise levels to prevent contamination of water resources and to build your fireplace, as well as other measures. The court responded to a complaint filed by indigenous representatives opposed to Cerrejón, the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, the National Environmental Licensing Authority, the National Mining Agency and the Autonomous Regional Society of La Guajira.

The mine has been sanctioned at least 17 times for its effect on the Wayuu, according to The Spectro.

Children fill the tanks with rainwater in a jaguy, a classic pool used through the Wayuu as a water tank. Pools like this can last for months during the rainy season, but an excessive drought has caused it to dry completely. Nicolo Filippo Rosso

Government officials did not respond to repeated requests to discuss the matter with Undark, nor to comment on the recent complaint filed with UN officials in Cerrejón, but also refused to comment directly, but in a report issued on 18 June, the company said it was “ready and willing to provide data to the various UN agencies to which the report was sent to provide the main points of the the company’s social and environmental performance.”

He also highlighted the company’s efforts to help neighboring ethnic communities, either before and during the Covid-19 crisis. While characterizing the complaint to the United Nations as founded on “inaccurate and biased data on Cerrejón’s social and environmental functionality, adding a completely false knowledge about the company’s water use and air quality, the company said that “it shares considerations about the well-being of The Wayuu Indigenous Communities”, and has spent millions of dollars in recent years to help educational projects. Organize vocational training, infrastructure projects and bottled water projects in the region.

In the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, Cerrejón “redirected his voluntary social investment of approximately $2.4 million to the La Guajira fitness system,” the company said in its statement. “We have donated over 100,000 medical materials to local hospitals, adding 3 enthusiasts and a laboratory to treat molecular testing [chain reaction through polymers] … [and] we have particularly expanded our water distribution program, which has allowed us to supply more than 12 million litres of drinking water to communities”.

“We strongly reject the accusations and the insinuation that we act inappropriately,” he added, “both in general and during the Covid-19 pandemic.”

As things stand, much of Cerrejón’s coal is destined for the Mediterranean, European and American markets. But the Wayuu are divided and have an effect on mine operations. After all, it is a massive economic engine for La Guajira, which accounts for up to 44% of regional GDP, according to the company’s own figures, and many Wayuu depend on the mine to locate the work.

“The statements and court cases discussed through foreign lawyers constitute only the position of two families and not the entire network or its government duly elected as members of the network,” is read in an official letter signed, among others, through indigenous leader Oscar Guariyu Uriana. (Luz Angela said he was a remote relative to her, and Uriana is a non-unusual surname among the Wayuu.) mine.

Wayuu at the Cerrejón mine. The mine is a constant source of employment and an economic engine in the region. Nicolo Filippo Rosso

But Luz Angela Uriana also blames the mine for the discord between the Wayuu. “Cerrejón has created this apartment among us,” he said. “But we deserve to focus on the wonderful white enemy rather than being enemies among our own people, our own family. Uriana added that even if she doesn’t object to development,” Cerrejón’s cash can’t make my son’s lungs healthy. “

Feria-Tinta, the lawyer representing the Wayuu at the United Nations, says that whatever the economic price of the Cerrejón mine, this has not represented a general positive replacement for Colombia’s indigenous communities. As a component of the UN complaint, Feria-Tinta and The Members of the Wayuu network represent the claim that the Cerrejón mine uses up to 24 million liters, or more than 6.3 million gallons, of water each day. Amid the scarcity of bottled drinking water due to the pandemic, the company has also infected local drinking water supplies, which are already under pressure, defenders say, accusations that Cerrejón officials and government officials have continually declared unfounded.

Whatever the reality, Feria-Tinta says that the presence of the mine in recent decades has done little for most of those who live there. “The mine did not gain advantages for the Wayuu. They are dying and affected by the disease,” he said. “La Guajira is the poorest region in the country right now, and Cerrejón has not replaced that.”

Rosa Maria Mateus, a member of the José Alvear Restrepo De Colombia Lawyers’ Collective (CAJAR), who is helping in the case of the United Nations, agreed. “The company has sold out as a benefactor that supports the region. But the truth shows something else.

The guajira, he added, is “a sacrifice.”

The arrival of Covid-19, say supporters of The Wayuu, now doubly true. “We put the petition to the United Nations in this Covid-19 context because we feel a deep and serious fear,” Mateus said. “Scientific reports indicate that there are populations that are more vulnerable and prone to higher mortality, so the virus kills them.”

“If it spreads widely in Guajira,” he added, “we are very afraid, because a giant of the population already has existing diseases, especially lung diseases.”

The UN complaint calls for the closure of the two wells closest to the Wayuu village of Provincial. David R. Boyd, a UN special rapporteur on human rights and the environment, showed that the UN had won the complaint, but said he can only comment more. Wayuu’s lawyers say they’re expecting a U.N. reaction this month.

Uriana, on the other hand, has little positive to say about the largest multinational operating in its region. “I do not oppose mining or the progress of the country. But they respect the rights of indigenous communities.

“We’re like ants opposite the wonderful, hard Cerrejón,” he added. “But we have dignity.”

The way humanity approaches this pandemic is how it can fight climate change. Subscribe to our biweekly newsletter, Clima in coronavirus time.