The motto: “Portugal is a country of gentle manners” was conceived through Portugal’s ancient authoritarian regime, which was overthrown in the remarkable 1974 Claveles Revolution. Through censorship and mass propaganda, the state had instilled confidence that in Portugal, unlike other countries, things happened non-violently, in an environment of benevolence and respect for others.

By reinforcing this narrative, state propaganda has sought to obscure the repressive nature of the dictatorship, whose police have persecuted, tortured and murdered members of the opposition, keeping a gigantic component of the population in poverty and ignorance.

Similarly, the disturbing romanticization of Portugal’s colonial history takes us out of a confrontation with the truth of colonialism and the way it still persists today.

Yes, we can be a warm and welcoming village. But if we want to achieve profound social change, we will have to deal delicately with our history and achieve a deeper understanding of what could be described simply as the mental composition of fashionable Portugal.

Our colonial heritage

Portuguese is the fifth most spoken language in the world. Can we believe what is behind this fact?

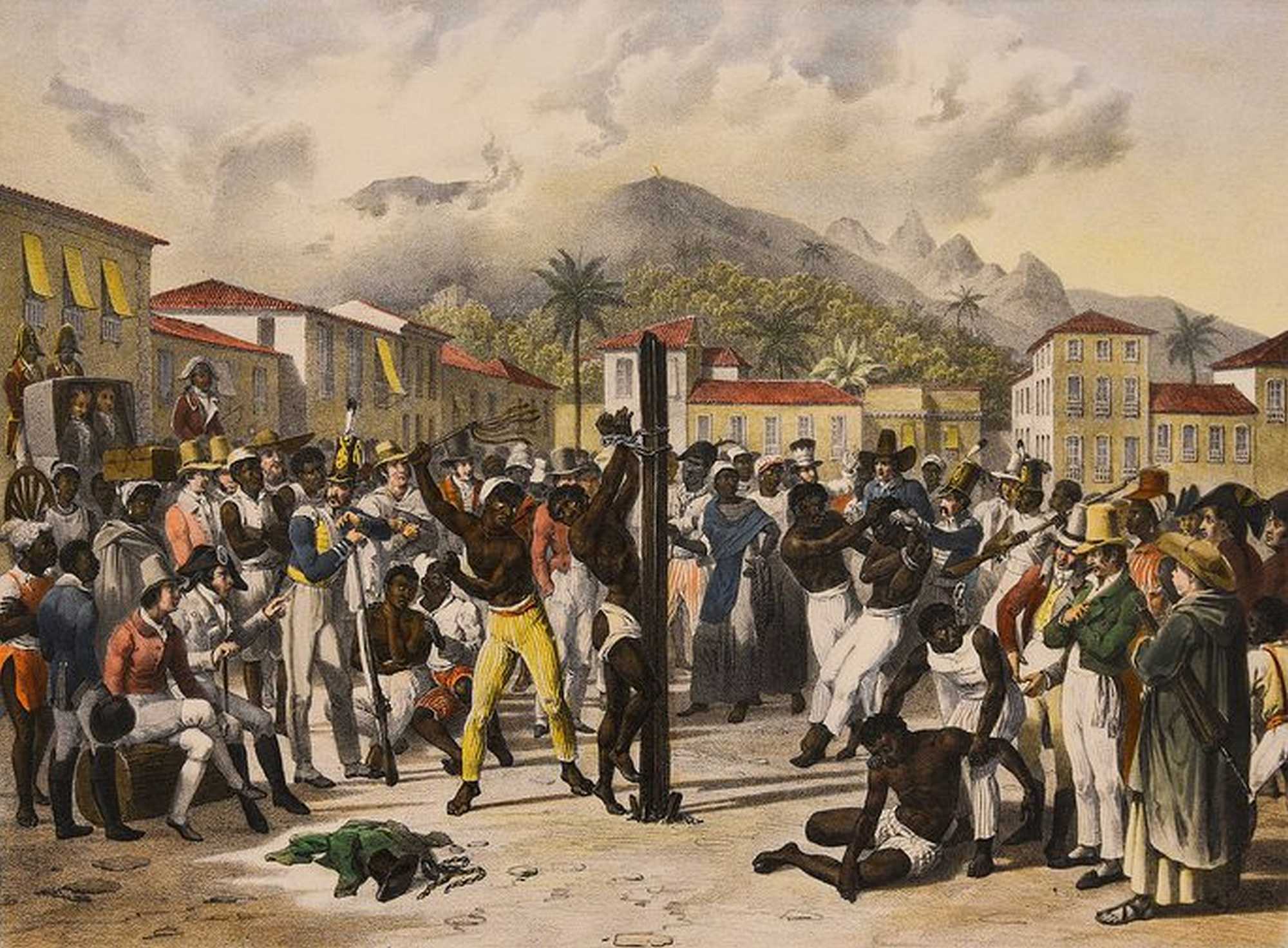

Portugal, the initiator of the transatlantic slave industry in the 15th century, subdued the black indigenous people of West Africa and sent them as slaves to Brazil.

From the 16th century to the end of the 19th century, we were one of the most prolific slave traffickers in the world, kidnapping, enslaving and deporting around 5. 8 million people abroad, more than any other colonizing country.

Despite Portugal’s withdrawal from the slave industry following the abolitionist motion just over two hundred years ago, its colonial business is far from over.

Portugal’s colonial empire, one of the oldest empires in the history of the world, existed for approximately six centuries, crushing Brazil’s indigenous cultures, the western and eastern coasts of Africa and strengthening its dominance in parts of India, Malacca. (Malaysia), the Maluku Islands (formerly known as “Spice Islands”), Macau (China) and Nagasaki (Japan).

Just over 40 years ago, Portugal was still waging colonial war, suppressing emerging independence movements in its African colonies: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique.

What is written in the history books and taught at school is the continuation of a narrative that served as the basis for colonialism: the concept of racial and cultural superiority of white Christian Europeans over “primitive” indigenous and black populations, related to the Romanticized symbol of the Portuguese colonial empire as a non-violent form of entrepreneurship and intercultural exchange.

In reality, colonialism is nothing more than the appalling slavery and genocide of other peoples for the extraction of resources and reasonable work, or in other words, capturing economic interest. Today there is little doubt that the white Western world owes its unheard-of wealth and its “proud” heritage of “civilizational” progress largely to the violent coertion of colonialism.

Throughout history, we have witnessed several to justify the “colonial project” and disassociate ourselves from the constant and indescribable cruelties that underlie it.

In the 1930s, with the slogan “Portugal is a small country”, the dictatorship in force in Portugal cultivated a sense of national pride derived from the dimensions of Portugal’s colonial empire.

However, in the 1950s, at a time when colonial empires were collapsing around the world, the regime faced the need to justify its colonial presence in Africa.

Therefore, it amplified a narrative of “luso-tropicalism” – an imaginary sense of Portugal as a multiracial and multitraditional country with an innate colonization of friendly and non-violent and a liberal attitude towards sex and interracial marriage.

Suppressing the realities of racism and colonialism, state propaganda materialized in statues, monuments and history books, ensuring a perfectly alienated edition of stone-engraved history.

The colonialism of the racial hierarchy

Colonialism goes hand in hand with a sense of racial hierarchy and the continued dehumanization of the oppressed, which serves to perpetuate a force of dating among other races that continues to consult our social habit to the extent that it is recognized.

In 1444, when The Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator became the first European to sail to sub-Saharan Africa, capturing captives directly, instead of buying slaves from North African intermediaries, the king of Portugal hired Gomes Eanes de Zurara, a cronist leader. Kingdom of Portugal, to write a biography about Prince Henry.

As John Biewen explains in the How Race was Made podcast, “[Zurara] stated that Prince Henry’s main reason was to bring [the sub-Saharans] to Christianity. Zurara described slavery as an improvement over freedom in Africa, where, she wrote, “they lived like beasts. “

They “had nothing good, but they only knew how to live in beastly laziness. “Zurara’s writings were widely disseminated among the Portuguese elite. In the following years, the Portuguese and their concepts about Africans broke the way as African slave industry evolved between countries such as Spain, the Netherlands, France and England.

The ideas of white supremacy and “development” were useful when colonizing nations sought ideologies that justified this kind of ruthless subjugation; as the African-American Ta-Nehisi Coates points out, “race is the son of racism, not the father. “In other words, the “race” as we know it today – without reference to fashion biology or anthropology – was manufactured through the early ideologies of colonialism to justify the unjustifiable.

Referring to Portugal with the true face of colonialism, Grada Kilomba, Portuguese writer, artist and psychologist, says: “We continue to feed on a romantic past, without associating it with guilt, shame, genocide, exclusion, marginalization, exploitation, [or ] dehumanization. »

His research continues: “We have not yet triumphed over denial. [Racism] is connected to a mental procedure rangeing from denial to guilt, guilt to dishonor, dishonor to popularity and popularity to reparation. [. . . ] I feel like we’re absolutely in denial.

Expanding our racism

With the expansion of the anti-racist motion in Portugal, all our national discourse is being questioned, confronting racism as a structural truth in Portugal “Are we a racist country?”- We find the consultation shocking.

Rui Rio, leader of Portugal’s first centre-right opposition (PSD) party, says that “there is no racism in Portuguese society. “Similarly, communist party general secretary (PCP) Jerome de Sousa states that “the overwhelming majority of the other Portuguese are not racist. “

Here we are dealing with two other definitions of racism.

One is based on the stereotype of a racist as an individual, who deliberately commits evil acts motivated by racial hatred.

Another definition describes racism as “a formula that encompasses economic, political, social and cultural structures, movements and ideals that institutionalize and perpetuate an unequal distribution of privileges, resources and strength among whites and other people of color” (Asa G. Hilliard) – a formula in which we are all socialized and that impacts on every degree of society, from the functioning of establishments to a hidden state of the brain of racial hierarchy, to particular acts of racism.

Confronting whites with the old formula of white superiority and their own internalized racism can be incredibly difficult, triggering many of the mechanisms of escapism and defense described as “the fragility of whites” (Robin diAngelo).

In the words of Layla F. Saad, “You will assume that what is criticized is the color and goodness of your individual skin, that your complicity in an oppression formula designed to gain advantages at the expense of BIPOC [Black, Aboriginal, People of Color] in a way you are not even aware of”.

National and Islamophobia

In this article, I focus mainly on Portugal’s historical oppression and the resulting systemic racism opposite the rest of the people of Africa. However, addressing other long-standing force relationships can also be much of what has been normalized lately in terms of ethnic and racial tensions.

Portugal’s elimination of its Islamic influences has been key since the slow recovery of Moorish territory by the Christian rulers of the Iberian Peninsula in the 13th century.

Marta Vidal, a journalist, writes: “Since then, the Portuguese identity has been built in opposition to the Moors, traditionally described as enemies. ” These times were shaped through the structure of a European identity that explained “in opposition to Muslims, and a crusade mentality that portrayed the relations between Christians and Muslims in contradictory terms. “

During the Portuguese dictatorship, these cultural divisions revived and amplified, as Vidal states: “With Catholicism at the center of nationalist narratives, the ultraconservative dictatorship portrayed Muslims as invaders and ‘enemies of the Christian nation’. “

Currently in Portugal

In 2018, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), a Council of Europe human rights monitoring body, issued warnings about the infiltration of far-right and neo-Nazi teams into the Portuguese police force and the political sphere.

Manuel Morais, vice president of the largest police union (Associaçao Sindical de Profissionais de Polacia), was forced to resign after condemning the presence of racist and xenophobic elements in the police, accusing the bodies of turning a blind eye to him.

In the 2019 national elections, André Ventura, leader of the new far-right politician “Chega” won a seat in Portugal’s national parliament.

In August, the brutal murder of Bruno Candé, a 39-year-old black Portuguese killed in full sun through a 76-year-old white veteran of the Portuguese colonial war, showed the reluctance of several politicians and a component of the general population. to settle for the blatant racism that motivates crime.

What is our role in systematically destabilizing the economy and livelihoods of these former colonies so that others have to let go of everything they have known and embark on a dubious new beginning?

But beyond the undeniable symptoms of a bubbling environment of racism, where all the alarms are ringing, blacks, Aboriginal people and other people of color and other ethnicities are lost to every degree of society, from access to housing and physical care, to low consumers in schooling and employment.

Most Afro-Portuguese have immigrated or are descendants of immigrants from former Portuguese colonies who still use Portuguese as their official language (Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Prencipe, Equatorial Guinea).

Many of them have come in search of a dignified life and end up settling in reasonable suburbs that can be allowed, many of them being highly segregated neighborhoods with a maximum concentration of descendants of Africans and other marginalized populations, such as Gypsies, who have a similar percentage. Socioeconomic difficulties.

In those areas, there is little investment of public money to improve the public, such as education, fitness or culture.

Because of the ancient oppression to which these populations have been subjected, they are much more likely to suffer from poverty and revel in serious limitations in their educational and vocational perspectives.

It is transparent that socio-economic constraints are in the tables here, and we can witness the appeal of a vicious circle that unites generations with the declining component of society: race is not the only conditioning factor.

But we might also ask ourselves: why did Africans have to leave their home countries in search of a dignified life in the first place?What has been our role in the systematic destabilization of the economy and livelihoods of these former colonies, so that other people will have to abandon everything they have experienced and embark on a dubious new beginning?

Cristina Roldo, a sociologist, says that “talking about racism is hiding another bureaucracy from inequality: gender, class, among others. These force relationships are articulated. “

To every degree of society, there is a convergence of other systems of oppression that intertwine to shape our daily lives, whether through racism, colonialism, capitalism, patriarchy, anthropocentrism, which reap benefits structurally for whites than for blacks, Aboriginal people and other people of color. Men than women. Fix rich over poor, heterosexual cisgender in LGBTQ, and humans in animals, plants and Earth.

Repair

Just as the existing formula still maintains the ideological and psychosocial situations that have produced and sustained colonial reality, we can also place in us what allowed this land to embrace diversity and allow the coexistence of other cultures and religions.

Repairing the ancient legacy of white supremacy and colonialism goes from denial to popularity in order to combine the systemic bureaucracy in which it still persists, ideologically, institutionally and psychosocally.

For this reason, this painting is directed to a basic procedure of social renewal, ultimately towards the creation of a society free of oppression and, in fact, capable of non-violent coexistence, not only among other cultures and ethnicities, but perhaps also with wonders. . and the deeply interconnected networked paintings of the living beings that inhabit this Earth.

This article gave the impression in Open Democracy – https://www. opendemocracy. net/