n n n ‘.concat(e.i18n.t(“search.voice.recognition_retry”),’n

In the second week of 2024, business leaders visited Gujarat, the home state of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. On the sidelines of the Vibrant Global Summit in Gujarat, one of the many talks in which India courted global investors. “Surrounded by many uncertainties, India looks like a new beacon of hope,” Modi boasted at the event.

He is right. Although global growth is expected to slow from 2.6% last year to 2.4% in 2024, India appears to be booming. Its economy grew by 7.6% in the 12 months to the third quarter of 2023, beating nearly every forecast. Most economists expect an annual growth rate of 6% or more for the rest of this decade. Investors are seized by optimism.

In April, some 900 million Indians will vote in the most important election in the history of the world. One of the main reasons Modi, who has been in power since 2014, is likely to win a third term is that many Indians see him as a manager of capitalizing on the world’s fifth-largest economy than any other candidate. Are they right?

To assess Mr Modi’s record The Economist has analysed India’s economic performance and the success of his biggest reforms. In many respects the picture is muddy—and not helped by sparse and poorly kept official data. Growth has outpaced that of most emerging economies, but India’s labour market remains weak and private-sector investment has disappointed. But that may be changing. Aided by Mr Modi’s reforms, India may be on the cusp of an investment boom that would pay off for years.

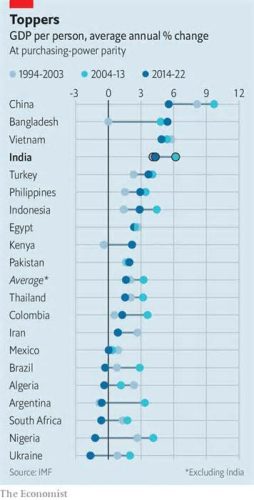

The overall expansion figures reveal strangely little. India’s GDP, in capita terms, after adjusting purchasing power, grew at an average rate of 4. 3% per annum. This figure is lower than the 6. 2% achieved under Manmohan Singh, his predecessor, who also served for ten years.

But this slowdown is not attributable to Modi: it is largely due to the bad hand he inherited. In the mid-2000s, the infrastructure boom soured. India faced what Arvind Subramanian, later a government adviser, called a double balance sheet crisis, affecting both banks and infrastructure companies. They found themselves saddled with bad debts, which hampered investment for years. Modi also took office at a time when global expansion was slowing, marked by the 2007-2009 currency crisis. Then came the covid-19 pandemic. The harsh situation caused the average expansion among 20 other giant low- and middle-income economies to fall, from 3. 2 percent during Singh’s tenure to 1. 6 percent under Modi. Compared to this group, India continues to outperform (see Chart 1).

In such a turbulent context, it is more productive to evaluate Modi against his stated economic goals: formalizing the economy, facilitating business, and breathing life into manufacturing. In the first two, it has d. In the third, its effects so far have been mediocre.

In fact, the Indian economy has become more formal under Modi’s government, but at a high cost. The concept was to move activity out of the underground economy, run by small, inefficient companies that do not pay taxes, into the formal sphere of large productive enterprises.

Modi’s most debatable policy on this front has been demonetisation. In 2016, he banned the use of two high-value notes, which account for 86% of the rupees in circulation, which surprised many, including in his government. ill-gotten gains by the corrupt. But at most all the money ended up in the banking system, suggesting that the scammers had already gone cashless or laundered their money. Instead, the informal economy has been crushed. Household investment and credit have plummeted and the expansion has likely taken a hit. Privately, even Modi supporters in the corporate network don’t mince words. “It’s a mess,” says one boss.

However, demonetisation would have arguably accelerated India’s virtualisation. The country’s virtual public infrastructure now includes a universal identity formula, a national payment formula, and a private knowledge control formula for things like tax documents. It was designed by the government of Mr. Singh, however, much of it was built under the Modi government, which has demonstrated the Indian state’s ability to carry out primary projects. Most retail invoices in cities are now virtual and maximum social transfers are transparent, as Modi has ceded bank accounts. to the fullest to each and every household.

Those reforms made it easier for Mr Modi to ameliorate the poverty resulting from India’s disappointing job-creation record. Fearing that stubbornly low employment would stop living standards for the poorest from improving, the government now doles out welfare payments worth some 3% of GDP per year. Hundreds of government programmes send money directly to the bank accounts of the poor.

This is a vast improvement over the old system, in which maximum social assistance was distributed physically and, due to corruption, did not reach its intended recipients. The poverty rate (the proportion of other people living on less than $2. 15 a day) fell from 19% in 2015 to 12% in 2021, according to the World Bank.

Digitalization has also likely brought more economic activity to the formal sector. The same goes for Davis’s other signature economic policy. Modi: A national goods and tax (GST), passed in 2017, which combined a patchwork of state taxes. taxes nationwide. The combination of homogeneous tax and payment systems has brought India closer than ever to a single national market.

This made business less difficult: Mr. Modi. TPS has been a “game-changer,” says B. Santhanam, regional head of Saint-Gobain, a giant French manufacturer with huge investments in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. The prime minister understands that,” adds the veteran production executive, referring to the desire to cut red tape. The government has also invested a lot of money in physical infrastructure, such as roads and bridges. Public investment increased from around 3. 5% of GDP in 2019. to almost 4. 5% in 2022 and 2023.

The effects are now being felt. Subramanian recently wrote that in 2023, as a percentage of GDP, net revenues from the new tax formula exceeded those from the old formula. This happened even as tax rates on many products were falling. The fact that more cash is coming in despite declining rates suggests that the economy is becoming formalized.

However, Modi is not content with formalizing the economy. Their third objective was to industrialize it. In 2020, the government introduced a subsidy program worth $26 billion (1% of GDP) for products made in India. In 2021, it pledged $10 billion to allow semiconductor corporations to build factories in their countries. One boss notes that Modi is personally struggling to convince executives to invest in sectors where they face few festivals and therefore may not otherwise do so.

Some incentives could help new industries find their feet and show foreign bosses that India is open for business. In September Foxconn, Apple’s main supplier, said it would double its investments in India over the coming year. It currently makes some 10% of its iPhones there. Also in 2023 Micron, a chipmaker, began work on a $2.75bn plant in Gujarat that is expected to create some 5,000 jobs directly and 15,000 indirectly.

But so far, those projects are too small to be economically significant. The price of manufactured exports as a percentage of GDP has stagnated at five percent over the past decade, and the share of the economy’s output sector has fallen from about 18 percent under the government beyond to 16 percent. And trade policy is expensive. The government will bear 70% of the cost of Micron’s plant, meaning it will pay about $100,000 per job. On average, prices are rising, driving up the cost of foreign inputs.

So what are the most important issues: Mr Modi or his successes?In addition to economic growth, investment in the personal sector needs to be addressed. Modi’s tenure has been slow (see Figure 2). But a boom is possible. A recent report by Axis Bank, one of India’s largest lenders, says the personal investment cycle is most likely to be reversed, thanks to the adequacy of banks’ and companies’ balance sheets. Announcements of new investment projects through personal corporations exceeded $200 billion in 2023. according to the Indian Economic Monitoring Centre, a think tank. This is the highest point in a decade and a 150% increase in nominal terms since 2019.

Although emerging interest rates have undermined foreign direct investment over the past year, companies’ stated intentions to invest in India remain strong as they seek to “de-risk” their exposure to China. Therefore, there is a possibility that Modi is giving a life to growth. If so, you will have earned a reputation as a successful economic manager.

It will be years before the consequences of Mr Modi are fully felt. Just as an investment boom might justify its approach, its strategy of social benefits as a replacement for task creation would likely prove unsustainable. The inability of local governments to provide critical public services, such as education, can also simply obstruct growth. Subhash Chandra Garg, Modi’s former finance secretary, worries that the government is too prone to “subsidies” and “giveaways” and that its “commitment to genuine reforms is no longer as strong. “And yet, many Indians will go to the polls. cautiously positive about the economic adjustments achieved through their prime minister.

© 2024 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.

From The Economist, published license. Original content can be discovered at https://www. economist. com/finance-and-activity/2024/01/15/how-strong-is-indias-economy–narendra-modi