For governments around the world, public health responses at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic included restriction to reduce transmission rates of the disease. contamination.

For a brief period, the world enjoyed a blue sky.

However, like the phenomenon related to the global currency crisis, the wonder of the blank air was short-lived when the world returned to recovery.

In the case of COVID-19, air pollutant levels recovered considerably once those lockdowns were lifted. In fact, in many cases, it has even worsened, depending on the main mode of shipping in the other countries.

For example, many other people looking to remain socially remote in cities around the world have refrained from employing public transportation, and have instead swapped their exercise and tram rides for more polluting personal car rides.

Even travel has been avoided through staff who can simply commute to work from home was compensated by building home deliveries or outdoor recreational trips.

In an effort to return to business as soon as possible after the pandemic, governments like the U. S. U. S. citizens issued stimulus bills and encouraged workplaces to reopen in an effort to “get back to normal. “

But this return to normalcy missed the opportunity to secure the pollutant discounts that had been achieved and increase the related benefits for the population and public health.

Each year, about 4. 2 million people die from exposure to pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM2. 5). These are inhalable wastes so small that they cannot be noticed with the naked eye and are emitted through the burning of fossil fuels.

An estimated 250,000 other people die from exposure to ozone (O3), which bureaucratizes pollutants emitted by cars and forces plants to react in the presence of sunlight.

Given the urgency of pollution-related health issues, our new study published in Atmospheric Pollution Research highlights the impact of pandemic restrictions, and reduced human mobility in general, on air pollution.

While previous studies have presented case studies on pandemic air quality in several countries or a variety of cities, this exam looked at knowledge of air pollutants from a collection of more than 700 cities (all cities for which this knowledge is available) worldwide.

Using data on weather patterns and beyond pollutant levels, we teach device learning models, which are systems that can locate patterns or make decisions from unpublished data, to wait for what pollutant levels would look like in the city if the pandemic hadn’t occurred.

Using this comprehensive pattern of cities, our device-based research highlights what can be achieved in each city, and around the world, through tweaks to shipping pattern locks.

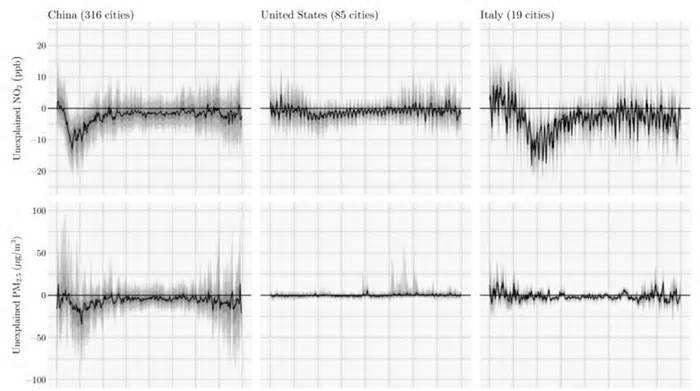

Our showed that cities in China, Europe and India have noticed significant decreases in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and PM2. 5, two pollutants strongly linked to fossil fuel burning and car use, which align with pandemic austerity levels, adding discounts on mobility.

As the charts show, NO2 degrees (and, to a lesser extent, PM2. 5 degrees) fell around February/March 2020. By comparison, NO2 levels in Italy replaced until March or April this year.

Ozone (O3) grades increased in the first part of 2020, as atmospheric chemical reactions that create ozone were driven by NO2 reductions. However, grades have generally declined in the northern hemisphere summer months, when O3 degrees typically peak.

Countries such as China and India have benefited from the largest discounts on particulate matter in ambient air. That’s because these two countries face some of the most serious health consequences of air pollution, which together account for more than a portion of pm2. 5 particles. related deaths worldwide.

The pandemic has provided an herbal experiment to perceive the dating between shipping modes and air pollutants. To deliver on some of the promises we saw of the immediate decrease in pollutants from the pandemic, cities can aspire to reshape mobility through active, pollutant-free activities. shipment

The evolution of mobility in 2020 has given us the opportunity to read about how our use of shipping systems contributes to pollution.

For example, New York and Tokyo experienced proportional decreases in pollutants as mobility in all types of transportation ceased during the first wave of COVID.

However, when it opened after the first shutdown, New York City’s mobility returned largely thanks to personal vehicle travel, far exceeding previous benchmark grades, and public transportation grades never returned to general grades. Meanwhile, in Tokyo, the use of public transport and the automobile have recovered at more equivalent rates.

Cities such as Brussels, Rome and Paris have created a total of 250 kilometres of new cycle paths as part of transport plans after the pandemic. Australian cities have not yet done the same: there is no shortage of cycling infrastructure.

After the pandemic, weekly motorcycle volumes on motorcycle routes increased by up to 140% in South Perth Foreshore, to 165% on the Outer Harbor Greenway in Adelaide and up to 169% on the Bay Trail in Brighton in Victoria.

Creating motorcycle lanes, as well as providing other shipping bureaucracy, such as vehicle sharing, gives cities a way to reduce emissions. day.

If governments want to protect their populations from pollution-related illnesses and deaths, they will want to create alternative shipping systems that aren’t aimed at private car travel.

Please indicate the appropriate maximum category to facilitate the processing of your application

Thank you for taking the time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your opinion is for us. However, we do not guarantee individual responses due to the large volume of messages.