Granny Gardeners’ assignment gives other people in Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) a sense of firmness and strength in uncertainty.

On September 10, Jess Housty, whose classic call is “C-agailkv,” went to Twitter and wrote, “Our Emergency Operations Center in Hae Hazaqv showed the first cases of COVID-19 in our community. “

Housty is the ceo of Qqs (Eyes) Projects Society (QPS), a non-profit charity Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) that aims to make young people and families thrive through cultural and networking programs.

While the first positive case of COVID-19 has now been shown in your community, Housty is thinking about how they can take care of others.

She says much of the way she’s going to do it is going to be through gardening.

“There is so little I can in the context of a global pandemic knocking on our door, but I can my lawn and the abundance I have to share,” says Housty.

“This morning, I went to eat a vegetarian meal on the net lawn and left myself at the doors of the elderly. “

– Jess Housty (@jesshousty) September 10, 2020

In his position at QPS, Housty taught the gardening categories about the pandemic.

“The first component of the pandemic is a call for attention to the importance of being self-sufficient in the event that COVID or other crises cause significant disruption,” he says.

“Knowing that the coming weeks are dubious and that our ability to temporarily slow down the spread of the network will set the tone for the winter months, I am grateful to have filled my pantry with canned food that our circle of relatives has grown – that we now have autumn and winter crops on the ground and that we are actively keeping the seeds for next year.

Why gardens

Since 2013, the network has been operating in food sovereignty systems.

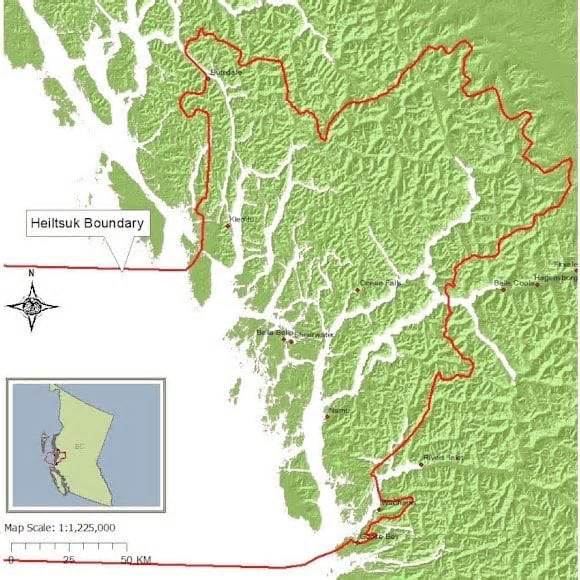

The territory Haíɫzaqv is located on the outer central coast of British Columbia. It extends from the edge of Vancouver Island, passing through all other coastal islands in the open ocean. About 120 years ago, the other people of Haszaqv accumulated in the village of Bella. Beautiful.

“The few Haíɫzaqv (about 1%) who did not succumb to influenza and smallpox accumulated here. We are descendants of those who survived the epidemics,” Housty said.

As a geographically remote community, culture is important, Housty says.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, this has an even greater concern.

“We were able to adapt much of what we did to be . . . COVID and help others during the pandemic. And it’s really charming and affirmative,” Housty says.

An expression of sovereignty

Food sovereignty is described as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally adequate nutrition produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to delineate their own food and agricultural systems”.

For the Heiltsuk nation, it is about recovering and strengthening the food security of its other people for thousands of years.

Housty defines food sovereignty as a holistic vision.

“Food is a medicine and food is building a community. In gardening, we express food sovereignty. We assume a duty to feed ourselves and those we enjoy with food that strengthens our bodies,” he says.

Gardening is something other people in Haíɫzaqv been doing since time immemorial, despite the unusual generalizations of “hunter-gatherers,” Housty explains.

Generalization continued with the fact that the Aboriginal peoples of the West Coast had no agriculture.

“One of the things I struggle with in my paintings on food security, food sovereignty, is this notion,” Housty says, “. . . that all Aboriginal peoples were hunter-gatherers and that our appointments with the properties and resources of our territories were casual and opportunistic. And the deeper I had been researching the wisdom of ancestral systems here, the more I learned what this concept was like.

On the territory of Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk), there are several examples of agriculture and classical agricultural methods.

Among the plants of the ria gardens are the clover roots of the riverbank and the roots of rice lily. Gardening carried out through the maintenance and favoring of the plots.

Like existing permaculture practices, plants have been desybated, rinsed, fed, decided and propagated. Research shows that these grass plots have been passed down from generation to generation.

Clam gardens are an example of Hazaqv’s gardening for millennia.

These clam gardens have been carefully maintained and maintained. Research shows that they have existed in Haíɫzaqv for at least 2000 years, and thousands of more years.

Radiocarbon dating of rock walls is complicated because scientists will have to locate chunks of biological matter between rocks or barnacle scars to take dating samples.

“Our ancestors have a very deep relationship with the choices and systems they cultivated to thrive for our mutual advantages and an act of reciprocity and kinship that has nurtured our other people since pre-reminiscence and knowing that . . . gave me that truth, ” said Housty.

Housty stores the profound replacement in the popularity of ecological knowledge.

“This is at odds with this concept of us as hunter-gatherers, and has completely reshaped my identity in relation to fitness and food systems. “

Indigenous families suffer from food insecurity

Housty back describes its territory of origin, this time from the point of view of distribution, chains and food transport. Food, adding dry products and new products, arrives at Bella Bella once a week by ferry or barge.

“For geographically remote communities. . . while the food arrives here, it’s not in your condition. It has traveled so far that other people carry this burden of guilt because of the carbon footprint of the products they consume,” he says.

Some culminations and vegetables are sent thousands of miles to Canada and then continue their adventure to geographically remote communities like Bella Bella.

Transportation prices are passed on to the consumer, who will eventually pay more.

“It is collected when it is ripe to be transported here. When considering the charge of creating this product here, it is temporarily out of success for [for] many community members,” Housty says.

“And then, the simple fact of knowing that what we have to have to come from the outside world is too expensive for other people to have access to it or, frankly, it’s not also a much higher nutritional value.

This is consistent with the findings of a PROOF report in March 2020.

“Lack of food confidence means that nutritious food is insufficient or volatile due to monetary constraints,” the report says. “More than one in eight Canadians are experiencing this situation lately. “This is higher than any previous national estimate.

The Yellowhead Institute also shared its considerations for lack of food confidence in Aboriginal communities.

His report reads: “With the pandemic and emergency measures such as restricting movement, final borders and food accumulation, which will lead to rising food prices and unemployment, these numbers will worsen. “

The pandemic and the emergency measures needed to protect communities have had an effect on large-scale food distribution.

“We have a fabulous grocery store here that works very hard,” Housty says. “But they were affected by COVIDArray. These chains from external sources seem a little more fragile and logistics is much harder to get what we want here. “

Grandma’s Gardens and Welfare

In the territory of Haíɫzaqv, the functioning of food systems is obviously vital during a pandemic. COVID had an effect on face-to-face workshops and ended larger network gardening activities.

QPS grows food on land to feed families and young people in its seasonal systems and opened a net lawn at Bella Bella in 2016.

In a general year, there is a collaboration with the Heiltsuk Health Center, and in summer a team of gardeners is sent to others with their orchards. However, the painting of this organization was interrupted by COVID, while food insecurity expanded.

Supplies in hand, rotated and adapted in Grandma’s gardens.

Seeds and plantations were shared, and physical distance devices and non-public coverage were used in the demonstrations.

Cheerful videos were used on social media to teach and connect.

In one of the videos on the Granny Gardening show, Housty holds a potato near the camera and smiles with pleasure.

“Look at those dark purple potatoes, ” he said. Our Haida parents enrich us and feed us in many ways, and now there is one more: Haida Gwaii potatoes grow effectively here in the homeland of Haíɫzaqv. “

Housty says Grandma’s gardeners were attracted to the assignment of what she gave them.

“A regime in terms of safety and stability in the early days of the pandemic . . . to help others familiar with special plant resources that they might not be aware of here,” he says.

“We actively use them . . . their families that are there in abundance, around us. “

Granny Gardens is a new symbol of the Victory Garden concept logo, Housty says.

Victory gardens were encouraged through the governments of World War I and II and people planted them not only to supplement their rations, but also to encourage them.

With Granny Gardens, the capacity for recovery is shared, but not the imperialist connotation.

Housty explains that Grandma’s detail of the project call honors and recognizes the millennia of women who paint together, harvest and grow an orchard in the land of Haíɫzaqv.

Housty stores some of the comments he earned from one of Grandma’s gardeners, who said: “Gardening has given me peace of mind, exercise, gratitude, wisdom of plant life and the thrill of harvesting for my circle of relatives of seven other people right now. pandemic and my own struggles. ” He gave me something else to look forward.

The comments of the wonderful gardeners also provide the reasons why they participate, adding the fitness effects of an active life and intellectual well-being.

“I had some pretty complicated disorders that I had to deal with professionally and personally,” said a fellow gardener from Housty. “And on earth my medicine. “

Another shared: “The gardening of the COVID-19 periods cared for my children and me. It was so glorious for them to see and eat the culmination of their work.

There is a detail of these food safety paintings that relates to collective paintings and industry with other communities.

“Gardening has had an effect on my life in a way I wouldn’t have imagined. The pandemic greatly increased my anxiety that I was already suffering,” said Housty, another garden grandmother.

“Going out with my hands on the ground with undeniable responsibilities to keep me honestly busy allowed me to succeed over the worst. Someone said that when other people plant gardens, they show that they have hope for the future.

What motivates Housty?

On October 13, 2016, Nathan E. Stewart, a tugboat and barge, sank after a vigilante fell asleep.

It poured 110,000 litres of diesel fuel, lubricants, heavy oils and other pollutants into Gale Pass, a village and cultural site in Haíɫzaqv. It was traumatic for the community.

“The root of this trauma came here because the panera in our territory struck through an oil spill in a position where other people would end up collecting dozens of marine and intertidal species from which they feed for their livelihood, which suddenly disappeared. . , almost overnight, ” says Housty.

To deal with this trauma, Housty, who is a mother and educator on earth, turned to gardening.

“When I think about why I started growing an orchard, it was an adaptation mechanism as I faced oil spill trauma,” he says.

“It was anything that gave me a sense of firmness and about my own food security. And it was healing to be outdoors and make these paintings and feed the living beings.

The following spring, Housty helped organize a network lawn that was planted in popularity among stakeholders working on the oil spill. QPS volunteered to lead fundraising efforts and structure as a network service.

“A great component of our motivation to create a wonderful area to honor lifeguards who were still suffering from trauma,” she says.

Network gardening mapping is a way to go.

“Vegetable cultivation may never update all ancestral foods that were affected by the spill. But knowing that you can give other people technical skills would give them a sense of control,” he says.

Today, as the effects of the pandemic continue, Housty remains motivated through the deep history of his people.

“When you’re looking for a long-term vision and you’re thinking about how long our other people are in our territory and thriving in our territory, the things they’ve been through. . . you’re starting to see those most vital patterns emerge,” Housty says.

He needs other people to realize “the incredible cases we’ve been through, resistance and prosperity. “

Odette Auger is Sagamok Anishnawbek and has lived for 21 years in the classical territories of toq qaymɩxw (Klahoose) also known as Cortez Island. His journalistic delight includes writing and generating for the assignment of the First People’s Cultural Council and local cooperative radio cortesradio. ca Odette’s paintings are financed in component through the investment of the Local Journalism Initiative in partnership with The Discourse and APTN.

Odette Auger is Sagamok Anishnawbek and has lived for 21 years in the classical territories of toq qaymɩxw (Klahoose) also known as Cortez Island. His journalistic delight includes writing and generating for the assignment of the First People’s Cultural Council and local cooperative radio cortesradio. ca Odette’s paintings are financed in component through the investment of the Local Journalism Initiative in partnership with The Discourse and APTN.