“+r.itemList.length+” “+this.config.text.ariaShown+”

“This.config.text.ariaFermé”

In 2020 it may have been, no one is in poor health and politics is half the universe.

The Democratic Party has just appointed Joe Biden and his vice president at its mid-July conference in Milwaukee, as Republicans prepare to rename Donald Trump in Charlotte, North Carolina. At his own earlier demonstrations, Trump heads to the booming economy to present his case. . for re-election, while Biden is suffering to agitate the crowds with his request to return to normal. Trump’s allies continue to announce conspiracy theories about the Biden family’s entanglements in Ukraine, leading desperate Democrats to push for a moment the indictment in the House. Both sides are waging a ferocious crusade across the country, knocking on millions of doors to lure the electorate in November.

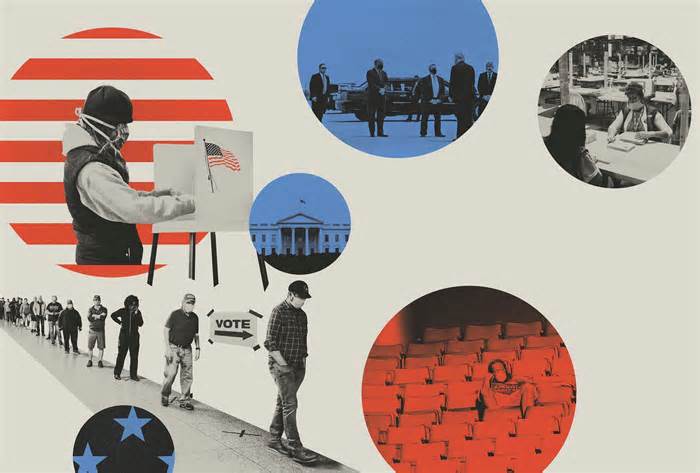

But in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has replaced everything from how the crusade is carried out to how we vote for what we value. It has overturned conventions, relegated fundraising and crusades to virtual dominance, and forced many states to temporarily replace the way other people get and present their ballots, with unpredictable and potentially disastrous results. Acute crises have refocused the nation’s attention, bringing problems such as public aptitude and economic and racial inequality to the forefront and prompting the public to reconsider the characteristics it needs in its leaders.

For four years, Trump has been the dominant force and the inescapable fact not only of national politics but also of American life. He now discovers himself displaced as a central figure in his own crusade through a scourge that does not meet any timetable, ideology or political objective. Just as the virus has replaced the way adults provide the accommodation in offices and young people go to school, causing entire industries in the process, it has led to a major replacement in the basic act of American democracy: how we decide on the president who will be guilty of ending the reign of pandemic destruction, facing its consequences, and shaping the ash-rising country. And as with so many other adjustments caused by the coronavirus, the practice of AMERICAN policy may never be the same again.

It would be a rare checkup: the high-risk re-election crusade of a pre-perspective traditionally divisive at a crucial time for the nation, a referendum on its provocative taste and disruptive vision, a control of its opposition scattered to determine what the aspect of a polarized political spectrum represents the mainstream. As the crusade enters his final three-month period, Trump is lagging poorly in national and state polls on the battlefield, as Americans give his lousy pandemic management a poor rating. But the end of Trump’s turbulent term will be written through the virus. We were surprised by its rise and spread in January and February, suspected life in general in March and April and slept many other people in complacency before waking up with their resurgence in June and July. Who knows what kind of October wonder you have in the store?

As a maxim in those days, presidential politics has adapted in a way that can be a little strange. For example, on Facebook on a recent Thursday night, Donald Trump Jr. is rapsodying with Mike Ditka, the former Chicago Bears coach, about physical abuse in childhood. “Perhaps a few more children in this country want a little more screaming than participation medals!” said Trump Jr., who wears an open-necked purple polo shirt and AirPods. Ditka, whose phone is tilted upwards towards his bottle brush moustache, is confused. “How can you say that?” he replied. “These poor children.”

The show, an episode of Trump Jr.’s Triggered podcast, embodies the content that Trump’s crusade feeds in line with hungry supporters. Another recent night, he presented “The Right View,” in which Trump Jr.’s girlfriend Kimberly Guilfoyle, Eric Trump’s wife, Lara, and Trump’s crusade assistants Mercedes Schlapp and Katrina Pierson, complement the demystified virtues of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID. remedy in a segment that will eventually accumulate more than a million visits. The crusade was already creating such online content, however, it is once again central to a world where meetings are likely to become widespread events.

Sign up to receive the Inside TIME newsletter with the exclusive TIME cover story.

Biden’s crusade also moved online, where his presence, like his candidate, is quieter and more traditional. “Events” are advertised to local supporters and organized around teams or problems in the constituency, just as they would on a general crusade. Biden’s wife, Jill, appears, Zoom, in a “virtual crusade stop” with the mayor of West Palm Beach, Florida, to communicate his plans for the elderly; Former Georgia governor Stacey Abrams organizes a “racial and economic justice roundtable” in line with Detroit business owners; Biden himself joins his former vice president, Barack Obama, for a 15-minute “conversation” about the Trump administration’s failures.

Despite the pandemic, Trump hoped to keep the rallies at the center of his political mythology. But an attempt to return to the level in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 20, became a debacle, with a scattered crowd, most commonly unmasked, that slightly filled the diminishing cover of the inner sand. Lately, he has settled for online “tele-meetings,” glorified convention calls that Trump supporters in key states are invited to pay attention a few times a week. At a recent voting meeting in Maine and New Hampshire, Trump obediently shouted out local Republican candidates, praised lobster fishermen, and promised to be difficult in handling the Canadian currency. Nearly 13,000 more people pay live attention, and thousands more people will eventually “see” the 30-minute audio stream. “The long term of our country will be explained through patriots who love our country and need to build it and make it bigger, bigger and more powerful, or it will be explained through the radical left. And radical left-wing Democrats are left-wing extremists. who hate our country,” he says.

In person, this kind of line would attract the roar of Trump’s crowd of fans, but online, the only answer is the silent scrolling of Facebook comments. Trump’s political adviser, Jason Miller, said tele-rallies had been a success. “Donald Trump’s genius is that he knows how to foster and build individual relationships with his constituents,” he says. But it’s transparent that virtual meetings don’t update reality. Not having the same source of mass flattery, the president has become accustomed to boasting of crowds lining the streets when he travels to states for official business.

Some local applicants, more commonly Republican, still have face-to-face occasions despite the risks. But the pandemic has become a vehicle for partisan attacks. When a Republican Senate candidate in Virginia released a video of himself attending a political occasion in the unmasked hall, the state Democratic Party took the symbol as “dangerously irresponsible.” Many democratic parties in the states have chosen to hold fully virtual conferences, yet several of their opposing Republican numbers have tried to make their way. The Texas Republican Party took its case to the state Supreme Court, which sided with the Houston mayor who had canceled his conference in person. The virtual meeting presented many technical difficulties: at one point, according to Texas Monthly, the pranksters invaded an online manufacturing plan document and added “Peepeepoopoo” to the calendar, and in the end, angry delegates expelled the president from the state.

It’s a similar story nationally. Democrats from the outset that the July conference in Milwaukee would not be feasible; they drove him back in mid-August and drastically reduced him, with delegates staying at home and voting remotely and Biden himself staying away. The Republican Party had a more bumpy road. In June, Trump moved the conference from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Jacksonville, Florida, in a dispute over the Democratic governor of North Carolina’s insistence on security protocols. As the number of COVID-19 instances in Florida increased this summer, party officials made a series of frantic adjustments, culminating in a final effort to organize the festivities at an outdoor stadium in the August heat. Finally, last July, Trump announced that The Jacksonville program would be recorded; The existing plan, which is still being developed, is to hold a small number of party meetings in North Carolina and ask the president to settle for the nomination with a televised cup at a venue to be determined.

The absence of classical conventions would possibly not be a loss. Events where the internal members of the smoke-filled rooms once elected presidential candidates and co-parliamentarians have become, in the age of fashion, little more than infomercial. But they serve as a major driving force for the parties’ fundraising, some other operation that came online in the coronavirus era.

The elegant deals that donors once paid tens of thousands of dollars according to the plaque to attend are now BYOB live streams. Campaigns have had to be artistic as the novelty fades. “When the house orders began, the crusades without delay began to organize virtual events: a fundraiser for Zoom, an assembly post for box organizers,” says Brian Krebs, who works at a virtual democratic crusade company called Rising Tide Interactive. “But the bar is rising now that many other people are moving away. You’ll have to have a special guest or some kind of crochet. People will not show up if they only communicate about 12 boxes. On the other hand, famous visitors will likely be less difficult to get when they can show up for their fundraiser without leaving Los Angeles. Texas Democratic Senate candidate MJ Hegar recently recorded an occasion with the cast of Senator Suconsistent withnatural and New Jersey, Cory Booker, none of whom set foot in Texas Hegar’s crusade volunteers have also been artistic to raise awareness, organizing an SMS voter registration consultation that has doubled as Taylor Swift’s listening party.

At that time, in an election, historically the crusades went from searching, identifying and persuading the electorate to push him into the polls. The Republican Party continues to do so, knocking on a million doors a week, the Republican National Committee says. But on the left, an intense debate erupted over the door-to-door ethics amid a plague. Research suggests that face-to-face conversations with the electorate are the ultimate and effective way to engage them. But top liberal teams and Biden’s crusade plan to knock on the door this year, as they find it too complicated for staff and the electorate. A growing organization, the Progressive Turnout Project, has had to suspend its operations in a dozen states after several staff members tested positive for COVID-19.

The irony is that more and more Americans are increasingly interested in political engagement this year. On a Fox News ballot in July, 85% said they were amazing or highly motivated to vote, and the percentage of respondents who told Gallup they were more excited than before voting 10 issues since 2016. Despite the difficulties of the voting pandemic, the primaries in states such as Texas and Georgia set a record for participation. At the same time, new voter registrations have declined due to the closure of government offices such as motor vehicle departments.

In Pinal County, Arizona, a small progressive organization called Rural Arizona Engagement had reached only a quarter of its voter registration goal when it stopped applying in March. Attempts to continue paintings over the phone were unsuccessful. Although Arizona is lately a hot spot for coronaviruses, the organization hopes to return to the voting box. “We believe that if we can stick to the rules [of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] and exercise our staff with them, as well as the other people we communicate with, this is a year that requires these paintings,” says Co-CEO of the Natali Fierros Bock Group.

The pandemic, he says, has made others aware of the importance of their vote. (This has also increased the rate of good fortune of pollsters: with so many other remote people in their homes, the more they are willing to open the door and communicate with a stranger.) Despite the strong public for wearing masks, the Pinal County Supervisory Board has made the decision not to wear a mask. and county sheriff Mark Lamb announced that he would not enforce the order to remain in the state home. (Lamb was forced to cancel a planned appearance with Trump at the White House when he was diagnosed with COVID-19 in June). “People are starting to join the dots,” says Fierros Bock, “and think about who is serving in those rooms, offices and the strength they exert. »

The pandemic landed amid the number one election season in the United States, forcing state election officials to adapt on the fly. The effects provide a review of the huge demanding situations and the mistakes that will stand during the general election.

One of the first tests was in Ohio, the number one of which was scheduled for March 17, a few days after the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic, the NBA suspended its season and the states of the country began the final quickly. When Republican Gov. Mike DeWine tried to delay number one, some plaintiffs sued and the courts determined that he did not have the authority to do so. Finally, at four o’clock on Election Day, when staff were already preparing for the election, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that the state’s director of fitness may order the completion of polling stations as an emergency measure. But the GOP-controlled legislature would not settle for DeWine’s proposal to move the vote in June, so mail-in elections were held with a deadline of April 28.

Other states temporarily reveled in the logistical, constitutional and political complexities of pandemic voting. At number one on Wisconsin’s April 7, held in time after a last-minute confrontation between its Democratic governor and the Republican legislature, many polling stations were forced to close when election agents for fear of security refused to show up. Hundreds of thousands of voters kept going, the state in socially remote queues for hours to vote. (A clinical examination subsequently related the election to an increase in the number of COVID-1nine cases, other researchers disagreed with this evaluation). Number one on Georgia’s June 9th melted amid staff shortages and technical problems, resulting in endless ranks and significant dismanding. that Democrats accused of being intentional are offered through Republican officials to suppress the vote. In New York, a state that usually votes almost entirely in person, election officials are blaming an unprecedented avalanche of postal votes for the fact that more than a month after the June 23 election, they have not yet declared the winner in some disputes.

In all cases, the coronavirus hit an already fragile system. “It’s a mistake to think that the pandemic is something other than other disorders in our electoral systems,” says Rick Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California, Irvine. “Interact with existing pathologies to make things worse.” Hasen’s latest recent book, Election Meltdown, released on February 4, the day after Iowa’s calamitous Democratic caucuses, whose backward effects illustrated the disruptions that evil electoral infrastructure can create even in the absence of a global epidemic.

Many states that have administered face-to-face elections for decades now seek to transfer to postal voting, allowing others to vote by mail without an apology or by presenting COVID-19 as a valid medical reason. But not everything. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a Democratic lawsuit to allow the entire Texas electorate to mail the ballots. In Georgia, the GOP Secretary of State has sent each voter a request for a vote for number one, but it will not do so for the general election. “I think it’s because there’s been a historic turnout, especially among the number one Democrat electorate, and [Republicans] don’t need to inspire that in the general election,” says Nse Ufot, executive director of the New Georgia Project.

Some states, adding California, Nevada, and Vermont, will send polls to all voters, joining five existing states with universal mail voting. Many others will mail a survey request to the entire electorate, but experts warn they may not be ready for the next flood. Postage, postmarks, notarization, or witness needs vary significantly from state to state. States facing pandemic-induced budget crises may not be able to pay for protective apparatus and millions of stamps, yet Congress has allocated only a fraction of the electoral investment they have requested. The U.S. Postal Service, at the point of insolvency bankruptcy, is not well equipped to deal with the outbreak, and Democrats allege that the popular agency, recently entrusted to a Trump ally, can also deliberately slow mail in urban spaces for assistance. The president. The state matrix’s voting procedures continue to replace as voting approaches, making it difficult for the electorate to stick to what is needed.

What election experts fear most is that all those demanding situations and adjustments can only question the outcome. Unless there is an eruption, election night will likely end without a transparent winner, and it can take weeks or months to count all the votes. “What we didn’t see in the primaries, even when there was confusion or weeks to count, was that someone called the elections manipulated or stolen,” says Aditi Juneja, a lawyer who equips the bipartisan national labor group in electoral crises. “We need to make sure that happens in the general election. If the result is not transparent or uncertain, leave room for actors to make crazy statements.”

That, of course, is precisely what Trump did. Continuing the pace that began in 2016, the president continually questioned the legitimacy of the vote, wrongly insisting that the postal vote is unsafe and that the elections will be “manipulated.” Trump says there is a difference between postal voting, which usually refers to mail ballots to the entire electorate, and postal voting, when the electorate usually has to request a ballot. But experts say there’s no difference in terms of security. Trump attacked Jocelyn Benson, Michigan’s Democratic secretary of state, for fitting in a “thug” when he posted mail-order ballot requests before the state’s number one, a step many of his opposing Republican numbers had also taken. “It’s not useful when you inject false or misleading information, hard-to-understand comments, and partisan speeches into the speech,” Benson told TIME. “This leads others to doubt the sanctity of the procedure and the validity of their vote. The fact is that we paint every day to make voting less difficult and harder to deceive.”

On July 30, Trump advised postponing the presidential election, prompting an immediate protest by Republicans and Democrats. “The considerations raised through the president are not valid in the state of Ohio,” Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose, a Republican, told TIME. “Both Ohio political parties have relied on our formula for 20 years and have worked hard for the electorate to take credit for postal voting.” As for the postponement of the election, “we’re not even considering something,” he says.

Election experts on either side fear that Trump’s pernicious crusade to undermine confidence in election integrity may be just a pretext for refusing to settle for the outcome if lost, leading the country into a constitutional crisis or worse. When a bipartisan organization of academics and former officials recently called the Transitional Integrity Project, iterating training produced “street violence and political stagnation,” said the organization’s organizer, Georgetown law professor Rosa Brooks. The Boston Globe.

When the truth of the pandemic began to take hold, Trump’s approval score first increased, as with presidents in times of crisis. The percentage of Americans who approve Trump, who has remained in a tight band throughout his tenure, reached 46% at the end of March, the highest point since his inauguration, according to the average polls held through FiveThirtyEight. Then he started to fall.

Today, only 40% approve of Trump’s performance, while only 55% disapprove of it. Americans now disapprove of their pandemic control across a 20-point margin. Biden has vital leaders on key battlefields such as Wisconsin, Florida and Michigan. States like Texas, Arizona, and Georgia, which Democrats haven’t won at the presidential point in decades, would possibly now be at stake. Many high-level Republicans are involved in their applicants about to be eliminated in the polls. “It’s hard to overestimate the extent and intensity of Trump’s weakness,” said Democratic pollster Margie Omero, a member of the Navigator study team who has interviewed more than 24,000 Americans at an ongoing foundation since March. “At first there was a small demonstration around the flag (other people sought to succeed) and then, when it was transparent that he didn’t take it seriously, you saw that change.”

Indeed, Trump was an unusually weak headline long before the pandemic, the only president who never passed 50% approval on Gallup’s normal follow-up. His current score remains above his lowest point of 35% in August 2017, following the violence of white supremacy in Charlottesville, Virginia. The existing merit of 8 Democrats’ points in the generic vote is roughly equivalent to their margin in the national vote in 2018. Biden has had a credit for Trump, posting margins similar to or higher than existing state polls even before the race entered. Much of the American electorate seems to have made a decision about this president from the beginning, abandoning him, and his party, without even chasing him.

Indicators that are generally correlated with the political fate of incumbents, such as the economy, would possibly not apply this year, according to Republican pollster Patrick Ruffini. The stage is too abnormal. Many others see the pandemic as a fluke caused by China and would possibly be receptive to the argument that economic suffering is not the president’s fault. Trump can also gain advantages from the popular emergency economic aid law that Democrats helped him pass. “The country can unite its leaders in a crisis if they feel things are going at least in the right direction,” Ruffini says. “The summer peak seemed to interrupt this option for the president. You’ll still have the option to show that things took a turn before November, but time is running out.”

COVID-19 replaced the content of the election indisputably. Optimism has plummeted: the percentage of others who think America is on the right track has fallen by 20 things since March. The pandemic has brought new urgency to problems such as access to physical care, inequality and the social safety net, while ruling out Trump’s favorite immigration and industry issues. “Voters are essentially the same, but the context of the 2020 election has replaced,” says UCLA political scientist Lynn Vavreck of Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America.

Trump’s flaws are suddenly more vital to the electorate. “For a long time, it was boring, but it didn’t necessarily replace anything in their lives: ‘I wish I’d stopped tweeting, but the economy is fine,'” says Lanae Erickson, senior vice president of left-wing liberal thinking. Tank Third Way, which has commissioned surveys and concentrated teams of thousands of electorates in suburban neighborhoods. “What he did to calculate his belief of Trump with genuine and terrible effects on them, their families and their country.”

When asked about Trump’s vision for the country, about respondents on the third track they volunteered as “interested” or “divisive” volunteers. Respondents also rejected their calls for “law and order” in reaction to street protests. When asked who to harm through Trump’s vision, 30 percent of suburban voters who were unsure said “all of us.” “People used to say LGBT to other people, women or other people of color,” Erickson says. “Today, 4% say immigrants, 6% say minorities, but 30% say everyone.”

Some participants from concentrated organizations were asked what they were looking for for the election. The answers were full of leadership qualities: others aspired to someone who was strong, compassionate, and listened to the experts. People agreed that Trump was strong (and questioned Biden’s strength), but he rerated the president catastrophically in the other two.

Just as Trump’s worst qualities have been amplified, Biden’s strength suddenly adjusts right now. When he announced his candidacy a year ago, he said he was forced to go through Trump’s equivocal reaction in Charlottesville. Some Democrats have criticized their mantra for a “battle for the nation’s soul” as too bloated or indifferent at a time when their rivals were making ambitious left-wing policy proposals. But a character-based campaign, tinged with nostalgia, is now not only foreboding but essential, whether you think Biden has what it takes to do it.

Trump’s crusade insists he sits for victory despite the headwinds. Public polls underestimate Republicans, says Miller, Trump’s political adviser, and the president’s supporters are more excited about voting at a 2-to-1 ratio. “Will there be other people queuing for two hours to vote for someone they don’t like?” He asks. But analysts on both sides are skeptical. “The vast majority of the electorate say that the pandemic and the resulting economic crisis are the highest life-saving unrest facing the country,” says Republican pollster Whit Ayres. “Efforts to replace the issue will likely paint with others already in favor of the president, yet there is no evidence that they are competing with others who want to join their coalition if they need to win.”

If the pandemic has revealed the flaws of American society, it has also revealed something else: some things remain too vital to get caught up in politics. Trump’s attempts to make the public exercise a partisan factor have more often failed. A large majority of Americans help their states’ pandemic restrictions, it’s more important to involve the virus than to revive the economy, think they want more, and, with resounding margins, help those dressed in the mask.

The national temperament has undergone a radical change in this tumultuous election year maximum. In the 3rd Way studies, the electorate communicated about emotions of sadness, anger, anxiety and fear. Surveyers’ reaction rates have skyrocketed because other single, confined people answer the phone only to have someone to communicate with. America is a divided country, but also a country that aspires to communion and solidarity. When a black man was brutally shot on video through police in Minneapolis, other people took to the streets in unprecedented numbers. Three-quarters of Americans said they helped recent protests over racial justice and that aid for the Black Lives Matter motion has increased, impressing political observers. It’s hard to believe that’s going down without Trump. But it’s hard to believe without COVID-19 as well.

When Americans one day scourge, the crusade with which it coincided will be an integral component of history. The United States has already held elections in difficult circumstances: wars, depressions, herbal disasters. Each time, in the face of deception, we vote on time; democracy has given us the opportunity to decide how we would get out of the crisis.

With reports through MARIAH ESPADA and ABBY VESOULIS