He has been described as “the worst kind of businessman,” but we now know that industrialist Moritz Hochschild also stored up to 20,000 Jews from the Nazis.

Moritz Hochschild was always on the move. In the early 1930s, he was discovered in the wonderful hotels of London, New York or Paris, or on the back of a mule, traveling the rugged roads of the mountains in search of the mineral veins of the Bolivian Andes. It was one of those trips to a remote mountain village, according to the legend of a circle of relatives, that the rich miner found here through a drawing of a local boy. The tycoon discovered the parody so funny that he decided to fund a scholarship for the artist to study drawing in Paris.

Hochschild can simply laugh at his expense. His sensible risk-taking made him one of the richest men in South America in the early twentieth century and gained him notoriety as one of Bolivia’s 3 “tin barons. “The trio, Hochschild, Simón Patiño and Oxford graduate Carlos Aramayo, had made their fortune in the Bolivian tin trade, which during the early part of the twentieth century was at the peak of demand for portions of airplanes and cans, and accounted for more than a portion of the country’s export earnings.

The barons were seen as a cartel: “a circle of oligarchs who negotiated with each other and had more strength than the state,” Bolivian historian Robert Brockmann told me. Tin was Bolivia’s main mineral export in the 1930s, and tin barons controlled 72%. of the country’s tin exports, paying only 3% of its profits to the government. The 3 mining barons are the most productive known for their ostentatious wealth, their influence on Bolivian politics and the exploitation of miners. “[Hochschild] a ruthless businessman; the toughest of the 3,” Edgar Ramirez, a former union organizer and archivist, told me. “The Bolivian president was looking to shoot him.

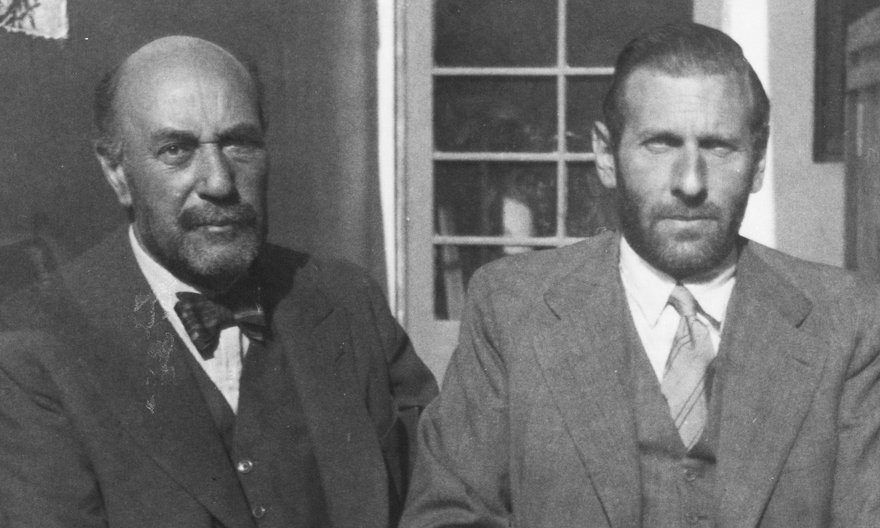

Hochschild, the youngest “baron” of several decades, was the only one who was not a Bolivian citizen. A middle-class German Jew born in 1881 in Biblis, a small town south of Frankfurt, Hochschild sought his fortune in Australia and Chile. before World War I, returning to South America as soon as the war ended to build his metallurgical and mining empire. During the 1930s and 1940s, Bolivia was swept away by waves of social unrest. imprisoned twice and threatened with execution. He escaped from his life, but fled into exile. As the country hurtled toward the 1952 National Revolution, one of its columnists, Augusto Cespedes, called Hochschild a “great pirate of mining finance. “”

But since then evidence has emerged that has forced Bolivia to reevaluate its view of Moritz, known as “Mauricio” Hochschild. that had taken over all of Bolivia’s mines when the industry was nationalized after the 1952 revolution. Documents from Hochschild corporations were stacked in boxes, filled into barrels, or thrown outside, exposed to the elements. Bolivia’s Library of Congress identified the former price of the archives and a team was hired to organize the documents under the direction of Edgar Ramirez and historian Carola Campos, who is now the archive’s director.