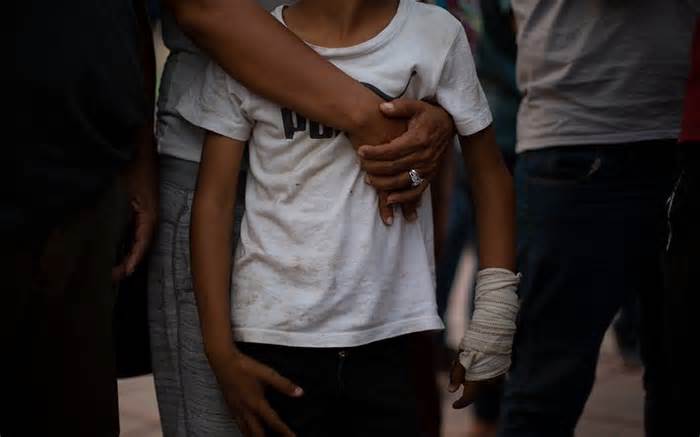

Karla Matute, 35, holds her son Joryí, 7, in a crowd outside El Parque Bicentenario in Tapachula, Mexico, on March 5. Joryí’s arm was injured in a confrontation outside an immigration office, and Matute had trouble getting medical attention. (Photo via Taylor Bayly/Cronkite Borderlands Project)

TAPACHULA, Mexico —— On a cool Monday morning in early March, dozens of other people — migrants and citizens — line up outside a public fitness clinic as traffic buzzes at rush hour.

A man’s knee is wrapped. Another has a large lump on his face. A teenager is pregnant. Mothers and fathers hold young children who cough, some fathers cough themselves. A child vomits on a pink cloth on a woman’s shoulder.

Meanwhile, Karla Matute, 35, holds the right hand of her son, Joryí, 7, whose left hand is wrapped in gauze on his wrist. They are migrants from Honduras.

When Matute arrives at the top of the line, he shows the nurse a letter from the Mexican government’s refugee company, known as COMAR, which gives her permission to seek loose remedy for her son. She says someone from the Red Cross told her he might have a damaged arm.

They arrived at the clinic, Matute said, after a public hospital in Tapachula told him they couldn’t treat Joryí because he didn’t have the asylum procedure and they’re not Mexican citizens.

Public directories list more than a dozen hospitals in Tapachula, but according to the interpretation of law and policy through the hospital, some turn away immigrants if they can’t afford, others treat them only after a referral from a number one care clinic, and others only after receiving the documents proving they are in the asylum system. The scenario is confusing for migrants seeking care.

The nurse asks, “Where do you live? I want your evidence of coping so I can continue to the consultation.

“Bicentennial Park,” Matute replies, referring to a downtown park where she and her son sleep in a tent.

The nurse up, confused.

“In the park?”

After discussions, Matute and Joryí are allowed to enter.

‘Open-air prison’ in southern Mexico traps for migrants

Medical care in Tapachula has not been built at this time. It’s a town of 350,000 other people in one of Mexico’s poorest and least resourceful states. Tens of thousands of migrants heading north are stranded here waiting for asylum meetings, humanitarian visas and other documents that will allow them to unload residency or continue their legal adventure toward The U. S. -Mexico border.

And as policies in Mexico and the United States have trapped migrants in Tapachula for months, the city’s fitness formula has been absolutely overwhelmed. The weight adds to the ongoing effects of the pandemic, limited quantities of medicines, high prices for medical tests, inefficient paperwork, and complaints of discrimination based on race and nationality.

But experts say the scenario in Tapachula would be much worse with the participation and determination of nonprofits, nongovernmental organizations and local fitness officials.

As a component of Mexico’s complex fitness system, the law ensures that all people, citizens and non-citizens, have access to critical care. This care is provided through a complex network of coverages that includes personal insurers (for those who can do so), employee-provided canopy, and various public canopy programs. But migrants don’t always have access to physical care, experts and advocates say. Communication between policymakers and providers about how to cover migrants and under which programs has been slow and unclear.

At the root of these demanding situations is the inability of Tapachula’s fitness formula to satisfy the desires of its own citizens. Medical providers face resource shortages and demanding structural situations caused by limited government funding. The state of Chiapas has a poverty rate that far exceeds that of other Mexican States; Almost 70% of the state’s population has the right to free public health in 2020, according to the Institute of Statistics and Geography of the Government of Mexico.

Migrants, especially women, young people and others with chronic diseases, are among the most vulnerable to these gaps and disparities.

When Erliwe Germain gave birth in September, she had been sleeping in Tapachula’s Central Park for five days. Hungry, tired and unable to find accommodation, she went to the public hospital, a party she described as complicated and frightening.

Germain gave birth in a room with seven other mothers. They didn’t even erase the baby, he said, gave him only an unidentified injection and received no follow-up care.

Germain had arrived in Tapachula with her husband, Dimitry Docile, a few weeks earlier. The couple, originally from Haiti, lived in Chile, but she said they suffered racism there and were looking for something more for their unborn daughter. They migrated north and eventually reached Tapachula.

Having a baby in Tapachula allowed Germain to offload the prestige of permanent resident in Mexico, providing him with more services. Germain’s cousin, Christela Saint-Louis, and her cousin’s husband, Dieulifoute Dorme, are not so lucky.

St. Louis said their one-year-old son was born in Chile before the family circle began the adventure to Tapachula with Germain. She suffers from persistent medical disorders that worsened the journey north.

Although UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, claims they can seek care and has given them the documents to do so, St. Simpson said. Louis, they haven’t gotten the assistance they need.

In Haiti, St. Louis said, doctors operated on her to draw fluid from her lungs and she got ongoing medical care after emigrating to Chile. However, after crossing the Darien jungle from Colombia to Panama for five days, his respiratory disorders began again. She said she had lost weight and that the pills she was given at a Tapachula clinic, an antibiotic and anti-inflammatories, did her no good.

Dorme, who got a rash during the trip, said the antifungal ointment he was given didn’t work either. His children have a good priority through local organizations, he and St. Louis, but in his experience, the attention of adults is minimal.

Leila Castro arrived in Tapachula in March with her 7-month-old daughter and 4-year-old son. They were dropped off at the Jesús El Buen Pastor shelter through immigration officials. Castro left two other young men in Honduras.

One recent night, Castro’s daughter developed diarrhea and then a rash on her shoulder. Castro said the shelter’s doctor and nurse gave him electrolytes for diarrhea but had no medication to treat the rash.

As the baby coughed, Castro hugged her tightly. The woman has a lung disease and her physical condition is already complicated, Castro said, but she intends to continue looking for a cure for her daughter.

Roberto Baez Castillo was arrested through the immigration government just one day after arriving in Tapachula last February. He was taken to Siglo XXI, the city’s migrant detention center, where he remained for 11 days.

When he got there, he said, he showed the government prescriptions for his three-month source of antiretroviral drugs, which he had earned in exchange for a fee in Panama to treat HIV. But the documents didn’t matter, said Baez, who has been living with HIV for 12 years.

“These are all the documents I gave them so they know I have my condition. And yet my medicines were thrown away in Siglo XXI,” he said. “They threw them in the trash.

As she waited outside the COMAR office, she recalled her long struggle to get the medication she needed to manage her condition.

Baez, who is gay, said he fled Cuba to escape continued violent discrimination by authorities. He spent a year in Peru without medicine. Eventually, he headed north to Panama City, where he nevertheless began receiving medical attention in mid-2019.

That day, he spoke with a member of UNHCR’s workplace in Tapachula, who told Baez that the firm would put him in touch with a local nonprofit that cares for HIV patients. you receive antiretrovirals, which puts you at a greater threat of headaches from the virus.

To perceive how many gaps exist for the migrant population of Tapachula, it is mandatory to read about the complex network of care available.

The vast majority of the number one physical care for migrants is provided through NGOs (non-profit non-governmental organizations) that add shelters, many of which are still recovering from the massive backlog of migration in recent years and the effects of the pandemic.

“Nothing here is enough,” said Laura Benitez, assignments manager at Global Response Management’s Tapachula site. Among other things, the foreign NGO supplies loose medicines to Tapachula without an appointment. No documents are required.

Benitez, who has also reveled in migrants in Tijuana, said things have been especially complicated in Tapachula since 2019, when U. S. demands that Mexico curb northward migration led Mexico’s municipality to institute a policy of confinement for migrants who entered the country from Guatemala. . The population in transition in the past has a static population, crushing health and care workers.

“The fitness formula has collapsed, basically,” Benitez said, “and there are a lot of NGOs. If we compare this to Tijuana, it’s as if we don’t have enough.

Global Response Management responds to the need of migrants for a number one intelligent care that they can access without problems. Recently, the company moved from a public clinic to a park complex called Estación Tapachula, where other services besides dentistry are available. Workers treat disorders such as dehydration, foot injuries, fever, and skin conditions.

The team of fewer than 10 people serves 20 to 50 people a day, and Benitez predicts that the numbers of some will increase as news of their new location spreads.

“I’m sure in a few weeks we’re going to have more patients,” she said.

Paperwork has been a major impediment for migrants seeking medical care, Benitez said. When migrants apply for asylum in Tapachula, their first point of contact is with the COMAR workplace to obtain an appointment date and time. During this appointment, they obtain official documents that allow them more fluid services, adding physical care in public clinics and hospitals.

However, Benitez said, until the end of 2021, asylum seekers were given appointments for up to six months, leading to delays for those with pressing physical needs.

“In six months they can’t work, they can’t go out, they don’t have money, they don’t have food to eat and they don’t have access to medical fitness because they don’t have the document,” he says. So it was a desperate moment. It was chaos.

Although wait times have improved, COMAR staff members are still beaten as asylum seekers continue to enter the city.

“People came to us crying. They didn’t know what to do,” Benitez said, “but now he’s getting better. It’s not good, but it’s not as bad as it used to be. “

Paperwork, however, is only one impediment among many. Haitian and African migrants face specific shortages of interpreters in medical settings, as well as widespread reports of systemic racism and prejudice against immigrants.

“It’s just about being migrants,” Benitez said. These are the ones with dark skin. “

Studies by Amnesty International and Haiti’s Bridge Alliance published in October contained accounts by black migrants in Tapachula of the “intersection of the bureaucracy of discrimination in physical care, based on language, race and nationality. “

And a 2020 study by Mexico’s Population Council on reproductive health care for migrant women in Tapachula found that discrimination and racism have a measurable effect and “act to the detriment of those women’s health. “

Migrants of various ethnicities reported physical reactions to this discrimination, according to the study, adding “high blood pressure, tachycardia, and symptoms of tension and anxiety. “

While the report highlighted efforts to hire Haitian immigrants as interpreters and translators, the researchers made it clear that those resources are sufficient.

Dr. David Jiménez, coordinator of the attention to the migrant population in the fitness district VII of the Ministry of Health of Chiapas, is a supporter of the order.

Every day he reviews the knowledge sent to him by COMAR and other agencies. Jimenez is guilty of 108 gym equipment – clinics, hospitals and ambulances – in and around Tapachula. There are also in each of the hostels. He answered several calls asking for ambulances and doctors from all over the city. Essentially, everyone in Tapachula is answerable to him for the government’s reaction to the physical care of migrants.

“There’s a magic word,” Jimenez said. It’s teamwork. “

Although the fitness formula in general faces challenges, Jimenez cited many tactics in which the Secretary of State for Fitness has controlled negotiations with NGOs such as UNHCR and UNICEF to facilitate medical care for migrants in Tapachula.

UNHCR has donated ambulances, masks, gloves and auxiliary ventilators to medical facilities in Tapachula and the region. It also provided access to prenatal ultrasounds and help for newborns.

In addition, UNHCR is collaborating with the local university to provide more interpreters for Haitian migrants and is generating leaflets and banners in Spanish and Creole that provide instructions on preventive physical care and how to seek services.

“And those documents also gain advantages for the entire population, because they are the ones that everyone needs, not just refugees and migrants,” said Pierre-Marc René, UNHCR’s public data associate in Mexico.

UNICEF is also filling gaps in maternal health care by hiring a gynaecologist and providing resources to children, adolescents and pregnant women. It sees about 150 patients a week, according to a UNICEF report from mid-March.

Brother Gonzales, 25, from Nicaragua, receives medical attention at the Jesus El Buen Pastor Shelter in Tapachula. He complains of bloodless symptoms, which are not unusual in shelters like the Good Shepherd.

Finally, with the assistance of the federal programs imss-Bienestar and Grupo Beta, Jiménez and his team have managed to ensure that maximum shelters in Tapachula have some point of medical attention and transportation to hospitals if necessary.

Despite these measures, some shortcomings remain.

Herbert Bermúdez, a worker at Albergue Jesús El Buen Pastor, said he used his own cash to buy medicine for migrants who may simply not find what they need at the source of medicine donated through the shelter.

In addition, COVID-19 continues to be a challenge in many shelters, creating shortages and safety considerations due to overcrowding, which has forced some to close, UNICEF reported in late March.

Jimenez said it was difficult at first to treat so many other people from so many cultures, but he said they had come a long way.

“I don’t think I know perfection, but I think we’re already getting to know each and every person: migrants from other countries,” he said.

But he expressed long-standing frustrations.

In his experience, Jimenez said, Haitians in particular are constantly in conflict with those who seek to help them, advancing in line. He wants everyone to stick to the formula set for them and go through the right channels.

Jimenez also said migrants prioritize their fitness over everything else, immigration appointments and their attempts to leave Tapachula.

“More than anything, you want to know how the migrant puts other things first,” he said. “The least of those things is his health. “

Benitez from Global Response Management also spoke about this phenomenon, although from another perspective.

“There are a lot of other people who want medical care or mental help, but they have other priorities,” he said. feed their families. “

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (named AMLO) addressed the inefficiencies of this physical health network in a large-scale reform of the Mexican physical health formula in early 2020. Health care reform was a major topic of discussion in his crusade in 2018.

Although the strengths and weaknesses of the old system, known as Seguro Popular, were nuanced, it guaranteed asylum seekers 3 months off from medical care once they had their asylum appointment.

An “open-air prison” in southern Mexico traps for migrants

AMLO’s government has created an entirely public option, known as INSABI, to make physical care more available to everyone, adding migrants. Public investment increased to 35% in 2020 to achieve those goals. This ended the three-month limit for asylum seekers and expanded access, at least on paper.

But communications about policies and expectations remain poor, according to some medical researchers, and there are many accounts of drug shortages and access problems for migrants and Mexican citizens. In addition, cases of corruption within hospitals have been reported that, when lowered, would possibly qualify patients for resources that would be free.

Experts also criticized Lopez Obrador for his severe lack of investment in physical care. An independent investigation in 2020 indicated that physical care in Mexico lacks resources of up to 658. 5 billion pesos. And despite some investment increases, this hole has not been closed.

Although the Chiapas Ministry of Health provides resources to migrants, most of the budget distributed through Jimenez comes from NGOs. Jimenez is proud of the progress his team has made, but more is needed, he said.

Jimenez said the NGOs he works with intensively will soon ask AMLO, who visited Tapachula on March 11, to “allocate more resources to the fitness system. “

Benitez agreed that there is a lack of resources from the Mexican government.

“The government is not doing enough,” he said. That’s why it’s vital that NGOs are here. “

Government reforms have also been affected by the ongoing pandemic. Mexico’s public hospitals, which serve others who need more than basic care, have been defeated and wait times in emergency rooms remain high.

Moreover, the personal and specialized remedy is beyond the economic success of many migrants.

Trapped in those currents, migrants like Karla Matute, the Honduran mother who asked with her son’s injured arm.

At the clinic, a doctor placed a sturdier tape on Joryí’s arm and referred him to the local hospital for an X-ray. Matute said the arm probably wasn’t damaged — Joryí would suffer more if she suffered — but it’s worth checking. to be safe.

They left the clinic with painkillers, but after going to the hospital, Matute went to the National Migration Office (INM). The night before I had heard that the firm could grant humanitarian visas to single mothers with children sleeping in the park.

For now, anyway, Joryí’s arm will have to wait.

She hopes to leave soon and head north to Monterrey, where she heard working there.

Additional reports provided by Jennifer Sawhney, Juliette Rihl and Salma Reyes. Translations were done through Jennifer Sawhney and Salma Reyes.

Cronkite News is the news department of Arizona PBS. News products are produced through Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Find a list and description of our rhythms here.

Privacy Statement

Learn more about what we do and how to stream our content on our streaming, virtual and social media platforms.

Learn how your news feed can use Cronkite News content.

Sign up for degrees.

555 N. Central Ave. Phoenix, Arizona, 85004

602. 496. 5050

[email protected]