As captured in archived weather data, the temperature near the Ramirez structure reached 96 degrees Fahrenheit that day.

What happened next is documented in reports from the Travis County Sheriff’s Office, Austin-Travis County Emergency Medical Services (EMS), and the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). to a Tesla contractor named Belcan Services a few days earlier, he seemed disoriented. A Belcan manager placed Ramirez in an air-conditioned van for about 10 minutes, according to a sheriff’s deputy, but Ramirez remained disjointed. The manager drove Ramirez about a mile to a medical trailer at the scene, where Ramirez showed “seizure-like activity,” vomited and stopped responding.

A Tesla paramedic, according to the same attached report, made the first 911 call in a while before 3:45 p. m. and then performed CPR, adding a defibrillation shock, until the Austin Fire and EMS Department workforce arrived. EMS doctors, who would continue CPR for more than an hour, recorded Ramirez’s frame temperature at 106, 106. 4 and 105. 1 degrees. in a frame bag filled with ice to try to cool him down, but Ramirez never responded to resuscitation measures. At 5:02 p. m. , he was pronounced dead.

Ramirez’s post-mortem report would eventually identify the cause of his death as hyperthermia, the medical term for an abnormally high body temperature, which can temporarily overwhelm human cooling mechanisms and thoroughly cook internal organs within minutes.

As shocking as it sounds, office deaths like Ramirez’s are not unusual in Texas. Arguably, the state is the deadliest in the country for staff in general and structural staff in particular, with warmth betting on a significant and formulationally under-recognized role at work. related illnesses, injuries and deaths. Despite Texas’ sweltering temperatures, state law does not require staff to take breaks. Federal law sometimes requires employers to stock offices, but in particular does not require breaks or other heat precautions. Unionized states in the country are also the only ones that allow top employers in the personal sector to opt out of staff reimbursement insurance. The risks of this forgetfulness formula tend to weigh more heavily on immigrant and non-white men.

Tesla, Elon Musk’s electric vehicle company, broke into employer-friendly Texas in 2020, with plans to build its new Gigafactory and move its headquarters to the Travis County site, located in a bend of the Colorado River a few miles from Austin’s airport. Behind the company lay a long history of employee protection violations, as well as allegations of injuries not reported to regulators in California and Nevada. Staff advocates in Central Texas sounded the alarm and the county government received promises of safety in exchange for tax breaks. But Ramirez’s case, which the Texas Observer spent five months investigating, not only exposes the state’s shattered safety net for manual staffing, but also shows that Tesla failed to comprehensively report accidents on compliance documents required by the county.

At 6:34 p. m. , Jessica Galea, an investigator with the Travis County medical examiner’s office, arrived at Tesla’s site. In the medical caravan, he saw Ramirez’s body still in the icy bag, his eyes bloodshot, dressed only in gray socks. according to its written report. A foreman then drove her a mile back to the site of Ramirez’s structure, “out of the way down a slope,” where he observed two barrels filled with ice and bottled water. “There were no shade resources,” he noted, and the foreman “could not specify when or how long his breaks lasted. “

According to court documents from Starr County, where Ramirez lived when not traveling for work, he died by will and his estate consisted almost entirely of a Chevrolet pickup truck “worth approximately $25,000. “

In an initial post-mortem report, signed in December 2021, the Travis County medical examiner identified Ramirez’s cause of death as “hypertensive atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” meaning high blood pressure and plaque buildup in the arteries. It wasn’t until later that the examiner’s workplace won EMS temperature records, a county spokesman said, and replaced his findings. (arrhythmia), seizures, coma, and death,” while blood pressure and plaque recede into a “contributing condition. “

On March 4 of last year, OSHA, the federal firm tasked with investigating employee deaths, issued an citation stemming from Ramirez’s death alleging that Belcan Services, his employer, exposed staff “to the identified hazard of superior ambient heat with a heat index of 98°F in direct sunlight. The fine is just $14,502, the maximum penalty for a bachelor “felony,” less than a portion of Tesla’s cheapest new car charge. Belcan disputed the subpoena and a trial was recently scheduled for July before an administrative law judge.

OSHA, a small agency with chronic understaffing, has struggled to maintain heat-related quotes due to a lack of regulatory clarity about the factor and challenges to employer success. In recent years, fines for heat exposure cases have been lifted in Ohio and Texas. — just one of many obstacles, advocates say, that prevent employers from being held accountable for the lives of staff like Ramirez.

In 2021, a Lone Star State employee died on both one-and-both 16. 5-hour assignments and a structure employee died one and both one and both 3 days, according to BLS data. An extra Observer investigation found that year from 2009 to 2021, Texas recorded more employee deaths than any other state, adding California’s most populous, while recording the highest employee fatality rate among the nation’s five largest states. Pennsylvania combined.

“Texas is just a horrible position for structure staff to do their jobs,” said David Chincanchan, policy director for the Workers Defense Project, a nonprofit that organizes Texas structure staff. “We are nowhere else in the country in terms of protection personnel. “

Hazards abound at structure sites. Federal fatality data identifies “falls, trips” and “transportation incidents” among the most common types of accidents. According to the BLS, deaths from “ambient heat exposure” are rare: only a few dozen a year across all industries in the country. But advocates and federal agencies argue that BLS statistics don’t capture warm deaths like Antelmo Ramirez’s.

Here’s how heat kills: When you do physical work, your body is exposed to internal metabolic heat and external environmental heat. To cool down, you increase blood flow and sweating. Cooling mechanisms can fail, leading to an increasing diversity of symptoms, adding dizziness, nausea and kidney damage. In the worst cases, heat stroke occurs; The internal temperature can reach 106 degrees in a matter of minutes, causing confusion, convulsions and death.

Heat-related office deaths go unnoticed due to weaknesses in information gathering and fatality investigation. For example, an overheated employee who gets dizzy and collapses would possibly only be recorded as a fall death. temperature readings) to diagnose death from hyperthermia. As the federal Environmental Protection Agency wrote in a recent report: “In many cases, the medical examiner would possibly classify the cause of death as cardiovascular or respiratory disease, without knowing for certain whether heat is a contributing factor. “

In a 2022 report, the nonprofit advocacy organization Public Citizen used a combination of BLS data, statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), California worker reimbursement claim figures, and educational studies to estimate that heat reasons 170,000 work-related people. injuries and between six hundred and 2,000 deaths consistent with the year.

For those who survive, heat stroke can cause permanent organ damage, cognitive impairment and increased vulnerability to heat. It’s confusing to know exactly what ambient temperature is harmful to workers, but in 2018, the CDC warned that 85 degrees “could be used as a screening threshold to avoid heat-related illness. Safety and OSHA experts point out that heat-related injuries are totally safe, thanks in large part to three undeniable measures: plenty of bloodless water, regular breaks, and time in the shade. . But many employers forego those precautions in the absence of effective regulation and in pursuit of profit.

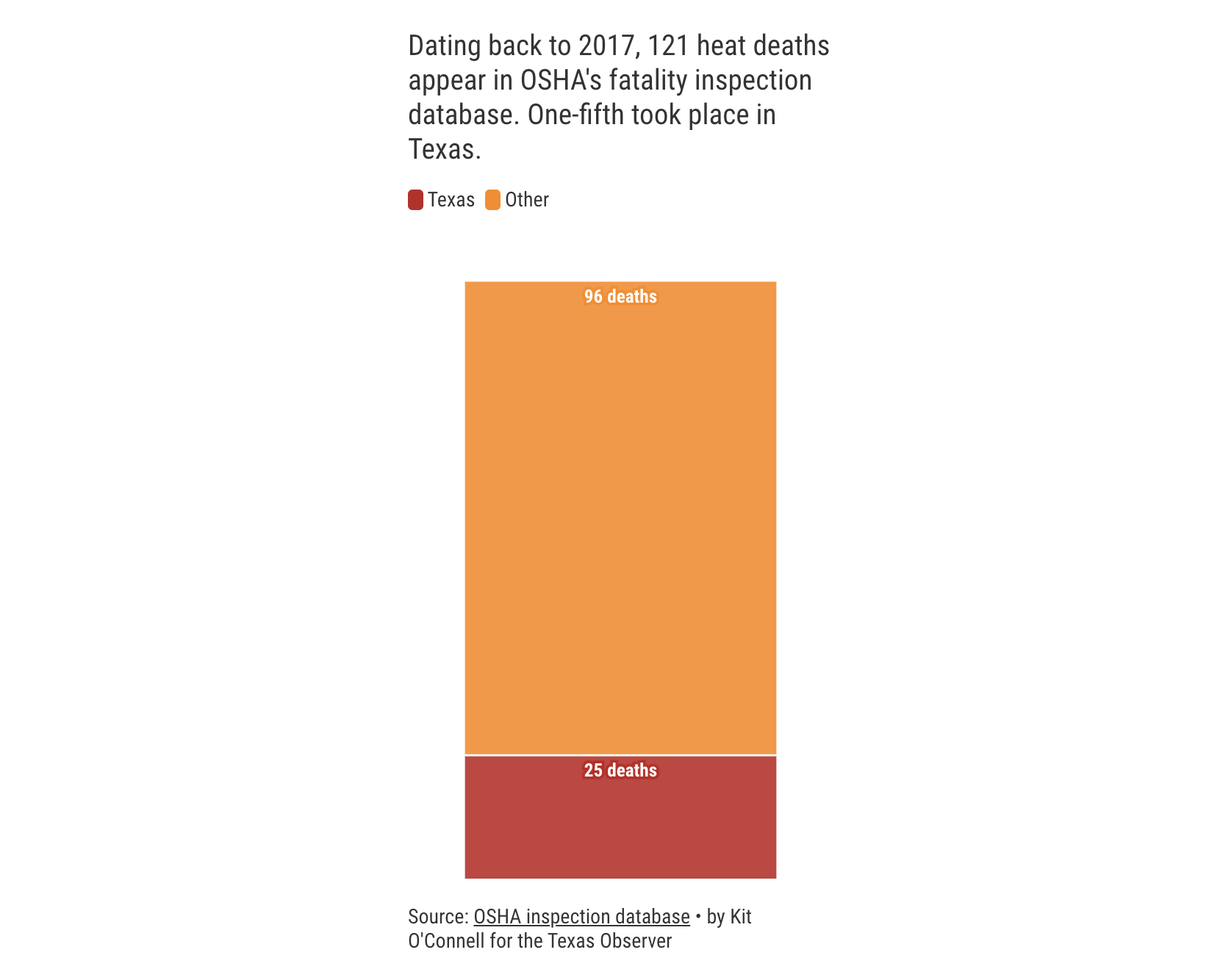

Due to employer underreporting and limited jurisdiction, OSHA investigates only about one-fifth of the number of employee deaths reported during the BLS year. 25 in Texas.

Since 1972, a federal research firm called the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has called on OSHA to adopt a popular federal thermal defense: a set of applicable regulations like those that exist for fall coverage and asbestos exposure. However, OSHA has not yet done so.

“We knew quite a bit about the risks of heat since we learned about the job,” said Jordan Barab, a former deputy assistant secretary for OSHA under President Barack Obama. a new regulatory issue, at least at the federal level. “

Some states have entered the regulatory gap with their own heat populations. These include California, Washington, Oregon and Minnesota, states with average temperatures cooler than Texas. According to Public Citizen, the California population could have reduced heat injuries by 30 percent. since its implementation in 2005. Texas has not taken any such action. Two Texas cities, Austin and Dallas, have followed their own rest policies for workers in the structure, however, the GOP-led state legislature has continually tried to kill local legislation and may also succeed this year. (Tesla’s site in Travis County is outside Austin’s city limits, so the city’s policy on breaks doesn’t apply there. )

Instead of a federal heat standard, OSHA relied on educational campaigns encouraging employers to protect their workers, as well as proactive site visits during warmer months to inspire more productive practices. The old general law called it the general duty clause, as it did in Ramirez’s case, which essentially states that employers will have to provide workplaces free of “recognized hazards. “Because the company itself refused to take into account a transparent standard of heat. In 2019, a federal review board dismissed a heat death case against a roofing company, and citing that decision, an administrative law ruled in 2020 that overturned five heat-related cases. Fines among U. S. Postal Service workers

“It’s a slow task to make quotes for general duty clauses,” Barab said. “Not only are they challenged and torn down, but it’s a lot more work. “

In 2021, Biden’s leadership, however, introduced the regulatory process to adopt a federal OSHA heat standard, but the process could take five years or more and could be halted if a Republican takes office in 2025. In its Notice of the proposed rulemaking, OSHA clarified that while peak heat deaths occur outdoors, some occur indoors. The company knows that agriculture and construction are among the most vulnerable industries, and climate change is expected to make those jobs increasingly dangerous.

One-third of heat deaths since 2010 were Hispanic, OSHA said, while Public Citizen said low-income people suffered five times more heat-related injuries than people with higher wages. overwhelmingly male), who make up the backbone of the state’s structures industry, accounted for 21% of overall employee deaths, while accounting for only 11% of the population.

OSHA also said in its advisory that “70 percent of [heat] deaths occur within the first few days of work,” as in Ramirez’s case, emphasizing the importance of “acclimatizing” new employees through the slow expansion of their duties.

In almost every respect, Ramirez’s case is archetypal. He’s a guy born in Mexico, running in structure in high temperatures, in Texas, with no legal right to breaks, who is new to the job. All this, with some other typical characteristic: As with all of us who go to work, someone enjoyed somewhere expected them to return home safely that day.

A public school instructor in the Houston suburb of Pasadena, Muñoz learned the news from an aunt as part of a series of chaotic phone calls from family members that occurred Tuesday afternoon and night of Antelmo Ramirez’s death. His aunt’s words – “your dad would have to [your father’s death]” – were hard to believe. Why would his father, who was fine, now die of an obvious central attack at work?

Two days earlier, Muñoz had been in Illinois for a brother-in-law’s wedding, but she had spoken with Ramirez by phone that night. It is one of the calls of the special circle of relatives where you end up talking more than expected. She planned to call back the next day, Monday, but she, her husband and their two children returned to Houston. No problem, he thought, he could call him on Tuesday after he was given paintings, a chance he would never have had. .

The surprise blurred those first days. A cousin arrived to take the children, then those over 3 and 5 years old. On Wednesday, she discovered herself at school making copies for a substitute. (“Looking back, I don’t know what I do in school,” he said. )And soon, she at the funeral in Starr County, where her father’s circle of relatives had made their American debut.

Antelmo Ramirez was from the small town of Agualeguas, about 30 miles from the U. S. -Mexico border. As a teenager, Muñoz said, his father immigrated to the Roma region of rural Starr County, on the Texas border. Ramirez was a farmworker immigrating along with other family members, following the onion and melon harvests, traveling seasonally to Illinois to paint cornfields, eventually marrying Muñoz’s mother and becoming a U. S. citizen in the ’90s. Munoz and his two younger brothers grew up in either Houston and Starr County, he said, while Ramirez transitioned from farm paints to refinery paints, specializing in scaffolding construction. saying.

During Muñoz’s childhood, Ramírez went for long periods to refinery concerts. She recalls that one of the first times she said goodbye before leaving for work, “I just thought he was going to leave us forever, I was screaming. So after that, in order to avoid the scene, he left “about 4 o’clock in the morning. “

She and Ramirez bonded through similar personalities. She described him in various tactics as shy, generous, frank and a bit peculiar. reminding him that “it’s better to eat at home. “

In his later years, Ramirez, who separated from the mother of his children while Muñoz was in school, fulfilled his role as a grandfather. When Muñoz, then living in Illinois, had her first child, Ramirez made everything from Texas with a full fajita meat cooler. She tried to tell him that there were also Mexican outlets in the north, but he insisted it wouldn’t be the same. Since Muñoz didn’t have a grill, he went out and bought one for the barbecue. At the time of her birth, now back in the Houston area, she arrived at the hospital but lasted a short time in the delivery room: “I couldn’t bear to see myself suffer. “

As his children grew, Muñoz saw a silly look of Ramirez reappear that he hadn’t noticed since he was little. He didn’t like being photographed, but she took it playing with her children.

After the burial, Muñoz nonetheless told his son and daughter what had happened, invoking the childlike words we use in conditions like these. it just stopped,” he remembers saying. Not long ago, his son, who is now 5 years old, said he was expecting a shooting star, so he might wish for his father’s return. “I guess he broke me,” he said, “but what broke me the most was that he didn’t say ‘my grandfather. ‘He said “your father. “

Reminders are everywhere. There’s the violin he helped buy her when she was a teenage mariachi, a tool she doesn’t dare play much more. In addition, the Tuesday of his death had been the day of the photo at school. “Then I see the image that was taken from me and my young people that day, and it’s like they robbed us of a sense of security,” Muñoz said, “because we know it’s not their time. “

A year before his death, Ramirez had also remarried. Reached by phone, his wife Mirtha Prado Franco said she still lives with Ramirez’s mother in Starr County and that her death has left her in limbo. “I have nothing,” he said. I’m in the air. “

Companies like Tesla and Amazon are employing intercity festivals to get maximum tax breaks, though critics say incentives rarely influence companies’ location decisions. While various levels of government in the Austin domain began debating tax deals, advocates of unions and smart government hesitated. One, Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced imaginable plans that same month to move the company’s headquarters to Texas to protest California’s COVID-19 restrictions, just two months after the fatal pandemic. On the other hand, Tesla’s history of protecting Tesla employees was already well established.

Between 2018 and 2020, media outlets such as Reveal, Bloomberg and USA Today found that Tesla continually misclassified and underestimated injuries to regulators at its California and Nevada factories. And from 2018 through March 2023, OSHA cited Tesla 49 times for 116 overall safety violations, twice as many citations as Ford and General Motors combined, 3 times as many safety violations, according to an Observer investigation of federal data. In July 2019, a 61-year-old man was discovered dead early one morning at the Nevada Tesla Gigafactory, despite the local medical examiner’s workplace telling the Observer that the death was naturally caused by high blood pressure and plaque.

“There’s a long history of citations through OSHA, much longer than other companies,” said Marcy Goldstein-Gelb, co-executive director of the nonprofit National Council for Occupational Safety and Health. “We are acutely aware of Tesla’s record of obvious negligence towards its workers. “

Despite those concerns, the Del Valley Independent School District, which serves an impoverished and unincorporated southeast of Austin proper, voted 7-1 in July 2020 to give Tesla about $50 million in asset tax relief. One administrator called the procedure “completely rushed. “

Immediately after the school district, Travis County, which lifted a self-imposed moratorium on economic incentives just because of Tesla’s proposal, passed its own tax proposal. Some networking and hard-working activists called for a delay, arguing that Tesla would come to Austin regardless of the deal, while a county commissioner “pleaded for some time” for more information. However, the commissioners followed the agreement on July 14, with 4 votes in favor and one abstention.

The county’s Tesla settlement promised at least $14 million in asset tax refunds over 10 years. In return, Tesla promised to create 5,000 new full-time jobs, which the county said would help citizens weather the COVID-induced recession. Even with the discounts, the county said it would get far more tax revenue from Tesla than from the sand and gravel mine that operated on the company’s desired 2,100-acre site. Human rights advocates, who added the Workers Defense Project, criticized it for its lack of independent compliance oversight, which the Workers’ Defense said amounted to allowing Tesla to “control itself. “About a week after the county vote, Musk revealed that Austin had beaten Tulsa for the plant. , and the initial structure allegedly began that month.

Soon, Workers Defense began receiving reports from staff about unsafe situations and injuries at the site. Last November, the organization filed court cases with the federal Department of Labor alleging that an unknown number of employees, hired through Tesla contractors, had their wages stolen. structure of the Gigafactory and that an employee had earned falsified OSHA protective education certificates. More Perfect Union also reported that staff fainted from the heat and suffered a serious hand injury at the site, while a review by an observer of OSHA inspections found that staff were exposed to the highest levels of carbon monoxide and one broke an arm.

Under its agreement with Travis County, Tesla will have to inform the county “of the number of injuries and deaths, if any, that possibly would have occurred in the construction” of the plant. In Tesla’s 2021 report, received from the county through the observer, the company provided an OSHA Form 300 injury record for single people, which lists 21 work-related injuries or illnesses, in addition to a crooked hand, a lacerated mouth and an injured elbow.

However, Tesla’s report to Travis County did not include all injuries or deaths that happened at the site’s structure. For example, this did not come with the death of Antelmo Ramírez in September 2021. And Hannah Alexander, an attorney with Workers Defense, told the Observer that she had spoken to several other staff members injured at the Tesla site in 2021 “whose injuries are not reported. “

According to the document provided by Tesla, the company appears to have reported only injuries to its own workers and not to its subcontractors and subcontractors. separate short- and long-term employers, but OSHA publishes aggregate injury information. Using the Texas Gigafactory address, the observer learned of at least six more injuries at OSHA 2021 knowing that Tesla failed to report Travis County, in addition to Ramirez’s death.

These omissions occurred despite Tesla’s own insurance manual, as presented to the county, which states, “All injuries, no matter how minor, shall be promptly reported to Tesla and the subcontractor(s). “

The Observer first asked Travis County about the injury hole in March. Toward the end of this month, Tesla submitted its most recent annual report to the county covering 2022, which the observer also received from the county. This time, Tesla back included a daily OSHA injury: directory of one hundred injuries, maximum workers with the non-unusual name of Tesla “production associate”, but for the first time, Tesla also submitted an additional document, which the county provided to the observer in PDF format called “List of entrepreneur events of 2022”. The new document lists 52 more injuries among workers at Tesla’s obvious contractors. Of the 52 injuries, 25 were workers at Belcan, the company that hired Antelmo Ramirez in 2021.

In early April, Travis County told the Observer it was asking Tesla to provide more injury data for the years leading up to 2022. The county also said it has not yet granted an asset tax refund to Tesla while it continues to review compliance.

“Travis County remains committed to protecting workers’ rights and improving operating conditions for those who build our community,” spokesman Hector Nieto said in a written statement. “That’s why the Travis County Commissioners Court includes needs in its economic progression incentive agreements. “. . . . Staff will assess whether any of the needs have not been met, how productive the non-compliance is, and provide recommendations to the Commissioners Court for further action.

The 10-million-square-foot Texas Gigafactory officially opened last April with a “cyber rodeo” party, featuring fireworks and Elon Musk in a cowboy hat, prompting the school district to send kids home early that day into traffic. Last April, the plant reached a production milestone of 4,000 Model Y cars in one week. Tesla is still building its site, the Austin American-Statesman reported in January, planning more than $700 million in additional construction.

The agreement between Travis County and Tesla also specified that Tesla would “make every effort to submit a successful application” to OSHA’s voluntary coverage program, which replaces proactive compliance and cooperation with periodic inspections. In April, an OSHA spokesperson told the Observer that the company had failed to apply.

Tesla, which disbanded its public relations team in 2020, did not respond to messages on its press email account or emails or calls to five senior workers and its chairman of the board.

In March 2022, when she learned that the medical examiner had replaced her cause of death with hyperthermia, she learned that her father’s death had been more than a twist of fate had been an injustice. He found a lawyer, who filed a lawsuit in Harris. County last May on behalf of Muñoz and his brothers opposed to Belcan Services Group L. P. and Tesla, Inc.

The lawsuit alleges that the corporations failed to exercise employees well, provide an office and provide medical care. Specifically, the lawsuit accuses the corporations of gross negligence, explained by state law as “conscious indifference” to known dangers. In Texas, that ban wants to be lifted in order to sue employers who have purchased workers’ reimbursement insurance, which Belcan and Tesla have done.

In March of this year, Muñoz told the Observer that in his phone call with his father two days before his death, Ramirez commented that he “felt like he couldn’t take a break” on Tesla’s website. Prado Franco, Ramirez’s wife, told the Observer that she had the idea there was no shade and that the site was regularly “neglected,” messy or neglected.

According to sheriff’s and fire reports, the observer received tactile data from six other people who were at the scene that day. Reached by phone, two of the six made brief comments. Gaspar Cano, known as a foreman on the sheriff’s report and as the user who drove Ramirez from the structure to the medical trailer, said “nothing at all” when asked if there were any protection issues. Cano said there were enough breaks and water before hanging up.

Felipe Benavides, also known as foreman in the report, said: “Everything went well from a security point of view. . . There is ice water, it breaks; because [Ramirez] is new to the job, he’s the least busy person,” adding that Ramirez had unspecified “medical issues. “

The observer was unable to receive the 911 call as of that day, as the Austin-Travis County EMS informed him that it had gotten rid of him, and is still awaiting the release of videos from the Travis County Sheriff’s Department dashboard camera.

In court documents, both Belcan and Tesla denied any wrongdoing and attributed Ramirez’s death to “pre-existing medical situations. “Tesla further criticized Ramirez for not “exercising caution. “situations that may have led to Ramirez’s death. The medical examiner said Ramirez “had no known medical history. “

Tesla also claimed in its filing that it is not liable because Ramirez worked for a contractor. Goldstein-Gelb, the employee protection expert at the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health, told the Observer that there is legal precedent for a company in Tesla’s position. guilty for what happens on his site, pointing to a specific settlement paid through Walmart in 2013 in Massachusetts.

Trials in the Harris County lawsuit and OSHA’s contested quote case are ongoing. In response to Observer’s requests for comment, a Belcan spokesperson said the company “does comment on notable legal matters. “

In the meantime, Muñoz will have to chart his own path to closure. To get there, he needs more data about what happened to his father, and he needs to spread the word about protecting employees so others don’t suffer the same fate. I don’t need to be stuck in September 2021,” she said, “and I need to be able to look at my kids and tell them I did what I could just to get answers and save them from this terrible thing that happened to their grandfather never happening. “

Muñoz also needs his father to be remembered for his perseverance and generosity, for his story of how he went from being a migrant agricultural painter to being a father to young people with professional careers: two teachers and a medical assistant. In honor of their father, the brothers received a scholarship at Roma High School for students who paint in the fields as he once did.

“Technically, he’s considered a victim, but he’s such a loud user that his call shouldn’t sound like ‘Oh, he’s just a victim,'” Muñoz said. dream. “

Editor’s note: The author’s wife, who was not involved in the production of this story, is hired through the Workers’ Defense Project.

Do you think open access to journalism like this is important?The Texas Observer is known for its fiercely independent and uncompromising paintings, which we are pleased to offer to the public for free in this space. We count on the generosity of our readers that this paintings is important. You can give a contribution for as little as 99 cents a month. If you help in this mission, we want your help.

Receive our detailed reports straight to your inbox.