Advertisement

Supported by

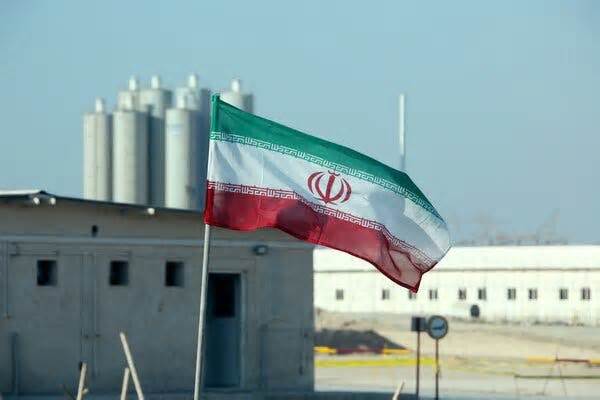

With its proxies attacking from many vantage points and its nuclear program suddenly revived, Iran is posing a new challenge to the West — this time with Russia and China on its side.

By David E. Sanger and Steven Erlanger

David E. Sanger and Steven Erlanger, who have been in Iran and the Middle East for several decades, reported from Berlin.

President Biden and his more sensible national security advisers believed last summer that the dangers of a confrontation with Iran and its proxies were well contained.

After secret negotiations, they had just reached a deal that led to the release of five imprisoned Americans in exchange for $6 billion from the frozen Iranian budget and some Iranian prisoners. Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen gave the impression of calm. Iran has even slowed uranium enrichment at its underground nuclear facilities, delaying its move toward a nuclear weapon.

Israel’s invasion through Hamas on October 7 and Israel’s corporate backlash replaced the situation. Today, U. S. and Israeli officials, along with a dozen countries combining to keep the industry in the Red Sea, face a newly competitive Iran. Having introduced attacks, from Lebanon to the Red Sea to Iraq, proxy teams have come into direct collision with U. S. forces twice in the past week, with Washington brazenly threatening airstrikes if violence does not continue. it doesn’t diminish.

Meanwhile, though little discussed during the Biden administration, Iran’s nuclear program has been put on steroids. International inspectors announced last December that Iran had tripled its enrichment of near-nuclear-grade uranium. According to rough estimates, Iran now has the fuel to make at least three atomic weapons, and U. S. intelligence officials estimate that the additional enrichment needed to convert that fuel into bomb-grade material would take only a few weeks.

“We are back to square one,” Nicolas de Rivière, a top French diplomat deeply involved in negotiating the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, said last week.

Taken together, the dynamic with Iran is more complex than at any point since the seizure of the American Embassy in 1979 after the overthrow of the shah. American and European intelligence officials say they do not believe the Iranians want a direct conflict with the United States or Israel, which they suspect would not end well. But they seem more than willing to push the envelope, enabling attacks, coordinating targeting of American bases and ships carrying goods and fuel, and walking to the edge, again, of nuclear weapons capability.

Adding to the complexity of the challenge is the dramatic expansion of Iranian aid to Russia. What began as a wave of Shahed drones sold to Russia for use in opposition to Ukraine has turned into an avalanche. And now, U. S. intelligence officials say that, despite warnings, Iran is preparing to send short-range missiles against Ukraine, just as Kyiv runs out of air defense and artillery shells.

This is a mirror image of a deeply replaced force dynamic: since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Iran is no longer isolated. It is an alliance of sorts with Moscow and China, two members of the UN Security Council that have long supported Washington in its attempt to restrict Iran’s nuclear program. Today, that deal is dead, terminated by former President Donald J. Trump five years ago, and Iran has two super forces not only as allies but also as sanctions-busting clients.

“I see Iran in a good position and has defeated the U. S. and its interests in the Middle East,” said Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at Chatham House. “Iran is active on all borders, resisting any replacement from within, while enriching uranium to very alarming levels. “

Biden took office with the goal of reviving the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, which contained Tehran’s nuclear program for three years until Biden took office. Trump retired in 2018. After more than a year of negotiations, a deal is almost reached. in the summer of 2018. 2022 to repair the essence of the agreement. This would have forced Iran to ship its newly produced nuclear fuel out of the country, as it did in 2015.

But the efforts failed.

For the next year, Iran accelerated its nuclear program, for the first time enriching uranium to 60 percent purity, just shy of the 90 percent needed to produce weapons. It was a calculated move intended to show the United States that Tehran was just a few steps from a bomb — but short of going over the line, to forestall an attack on its nuclear facilities.

In the summer of 2023, however, Brett McGurk, Mr. Biden’s Middle East coordinator, quietly pieced together two separate deals. One got the five American prisoners released in return for several imprisoned Iranians and the transfer of $6 billion in Iranian assets from South Korea to an account in Qatar for humanitarian purposes.

But the second deal — one Mr. Biden did not want revealed — was an unwritten agreement that Iran would restrict its nuclear enrichment and keep a lid on the proxy forces. Only then, the Iranians were told, could there be talks on a broader deal.

For a few months, it works. Iranian proxies in Iraq or Syria did not attack U. S. forces, ships roamed freely in the Red Sea, and inspectors reported that enrichment had slowed considerably.

Some analysts say this is a transitory and deceptive calm. Suzanne Maloney, director of the foreign policy program at the Brookings Institution and an expert on Iran, called it “Hail Mary, which they hoped would maintain some calm in the region after the election. “”

American intelligence officials say Iran did not instigate or approve the Hamas attack in Israel and probably was not even told about it. Hamas may have feared that word of the attack would leak from Iran, given how deeply Israeli and Western intelligence have penetrated the country.

But as soon as the war against Hamas began, forces under Iran’s command introduced the attack. However, there were significant indications that Iran, facing its own internal problems, sought to restrain the conflict. From the beginning, Israel’s war cabinet discussed a preemptive strike against Hezbollah in Lebanon, telling the Americans that an attack on Israel is imminent and part of an Iranian plan to attack Israel from all sides.

Mr. Biden’s aides pushed back, arguing that the Israeli assessment was wrong, and deterred the Israeli strike. They believe they prevented — or at least delayed — a broader war.

However, in a few days, the risk of war with Hezbollah has resurfaced. The organization fired dozens of rockets at an Israeli army post on Friday and Saturday in what it called a “preliminary response” to last week’s killing of senior Hamas leader Saleh al-Arouri. in Lebanon.

Some members of the Israeli government, such as Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, have warned that complacency about Hamas’s intentions will not be replicated with Hezbollah, which has reportedly aimed as many as 150,000 missiles at Israel and trained some of its troops, the Radwan Force. , for a cross-border invasion.

But in Washington, the fear is now less for a Hezbollah attack on Israel than for an Israeli attack opposed to Hezbollah. The U. S. has told Israel that if Hezbollah crosses the border, Washington will attack Israel, but not the other way around.

Hezbollah appears to have been careful so far not to give the Israelis an excuse for a military operation. Still, Iran has built Hezbollah, the most powerful force in Lebanon, as protection for itself, not the Palestinians. Hezbollah is a deterrent against any major Israeli attack on Iran, given the carnage its thousands of missiles could inflict on Israel.

This is one of the main reasons Iran needs to keep Hezbollah out of the war in Gaza, said Meir Javedanfar, a senior lecturer on Iran at Israel’s Reichman University. Otherwise, Israel could go straight after Iran, he said, noting that former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett has long advocated cutting off “the octopus’s head, just the legs,” like Hamas and Hezbollah.

“I see little interest in Iran right now,” said Mrs. Maloney of the Brookings Institution, “because they realize their interests to the fullest. “

But American officials say that Iran does not have operational control over many of its proxies, and that the intensity of the attacks far from the Lebanon-Israel border could well be the spark for a larger conflict.

Iranian proxies in Iraq and Syria have carried out more than a hundred such strikes, which have resulted in brief counterattacks when they have caused American casualties. On Thursday, a rare U. S. missile strike in Baghdad killed Mushtaq Jawad Kazim al-Jawari. , deputy commander of an Iranian-backed defense force that “was actively concerned with making plans and carrying out attacks against U. S. personnel,” the Pentagon said.

The detail of the clash with the greatest immediate global impact centers on the Red Sea, where Houthi forces in Yemen, using Iranian intelligence and weapons, are targeting what they call “Israeli ships. ” all ships with heat-seeking missiles that cannot distinguish between targets and the fast ships used to board and seize oil tankers.

When the U.S. Navy came to rescue a Maersk cargo ship under attack last weekend, the Houthis opened fire on Navy helicopters. The Navy pilots returned fire and sank three of the four Houthi boats, killing 10, the Houthis reported.

Maersk, one of the world’s largest airlines, has suspended all transits through the Red Sea “for the foreseeable future” as it is taking the fastest direction between Europe and Asia: the Suez Canal. Companies around the world, from Ikea to BP, are already warning about delays in the supply chain.

Washington has pulled together a coalition of nations to defend the ships, but it is heavily dependent on the American naval presence. And so far Mr. Biden has been reluctant to attack the Houthis in Yemen, but that appears to be changing, officials say.

The United States and 13 allies signed on to a statement last week giving what an administration official called a “final warning” to the Houthis to stop “these illegal attacks and release unlawfully detained vessels and crews.” It did not mention Iran.

The Pentagon is fine-tuning its plans on how to attack Houthi release sites in Yemen, and some sort of attack on Houthi assets in Yemen will most likely occur as soon as the attack occurs, the officials suggest, as a strict warning to be heeded. Repair deterrence.

“At this point a significant military response is needed against the Houthi rebels, who are really Iranian pirates,” said James G. Stavridis, a retired admiral. “Our experience with Somali pirates years ago shows that you can’t just play defense; you have to go ashore to solve a problem like this. That is the only way for Iran to get the message.”

“The idea that we’re going to patrol the Red Sea, along California,” with “half a dozen police cars (our boats there) is not realistic,” he said.

Biden faces tough choices. He withdrew from the Middle East to devote himself to the festival and deterrence of China. Now it’s being sucked back in.

“The U. S. has built a deterrence matrix, indicating that it is interested in a regional war but willing to interfere in reaction to Iran’s provocation,” said Hugh Lovatt, a Middle East expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations. U. S. aircraft carriers and troops further expose Washington, he said. “So this matrix of deterrence may simply be a driving force of escalation. “

Above all such conceivable conflicts is the long-term Iran’s nuclear program, with its long-term prospects of direct confrontation with the West.

Years of diplomatic negotiations, covert moves to disable Iran’s nuclear centrifuges, and Israeli assassinations of Iranian scientists have focused on a single goal: extending the time it would take Iran to produce nuclear fuel. a bomb. When the 2015 deal was reached, the Obama administration celebrated its greatest accomplishment: that deadline, it said, of more than a year.

Today, as Rivière, now France’s ambassador to the UN, pointed out, “we are talking about a few weeks,” a scenario that in years past would have almost provoked a crisis. (However, turning this fuel into a working pump would likely take a year or more, giving the West more time to react. )

Biden’s leadership has said little, officials who speak anonymously admit, because its features are so limited. Since Iran supplies weapons to Russia and promotes oil to China, there is no Security Council action.

And Biden’s advisers have given up on reviving the 2015 agreement because it is now obsolete. As negotiated, it would allow Iran to produce as much fuel as it needs from 2030.

“Iran gets rich because it can,” Maloney said. Their purpose has been to wait for the tension to end and give themselves the option of a weapons program. “

David E. Sanger covers Biden’s administration and national security. He has been a reporter for The Times for more than 4 decades and has written several books on demanding situations for U. S. national security. Learn More about David E. Sanger

Steven Erlanger is Europe’s leading diplomatic correspondent based in Berlin. He has reported from more than 120 countries, including Thailand, France, Israel, Germany and the former Soviet Union. Learn more about Steven Erlanger

Advertising