Why do the other blacks vote en masse for Democrats in each and every election?

Kellyanne Conway highlights her commitment to the circle of family members first

Should democrats expect the electorate to electorate Biden, a plagiarism and cheating shown?

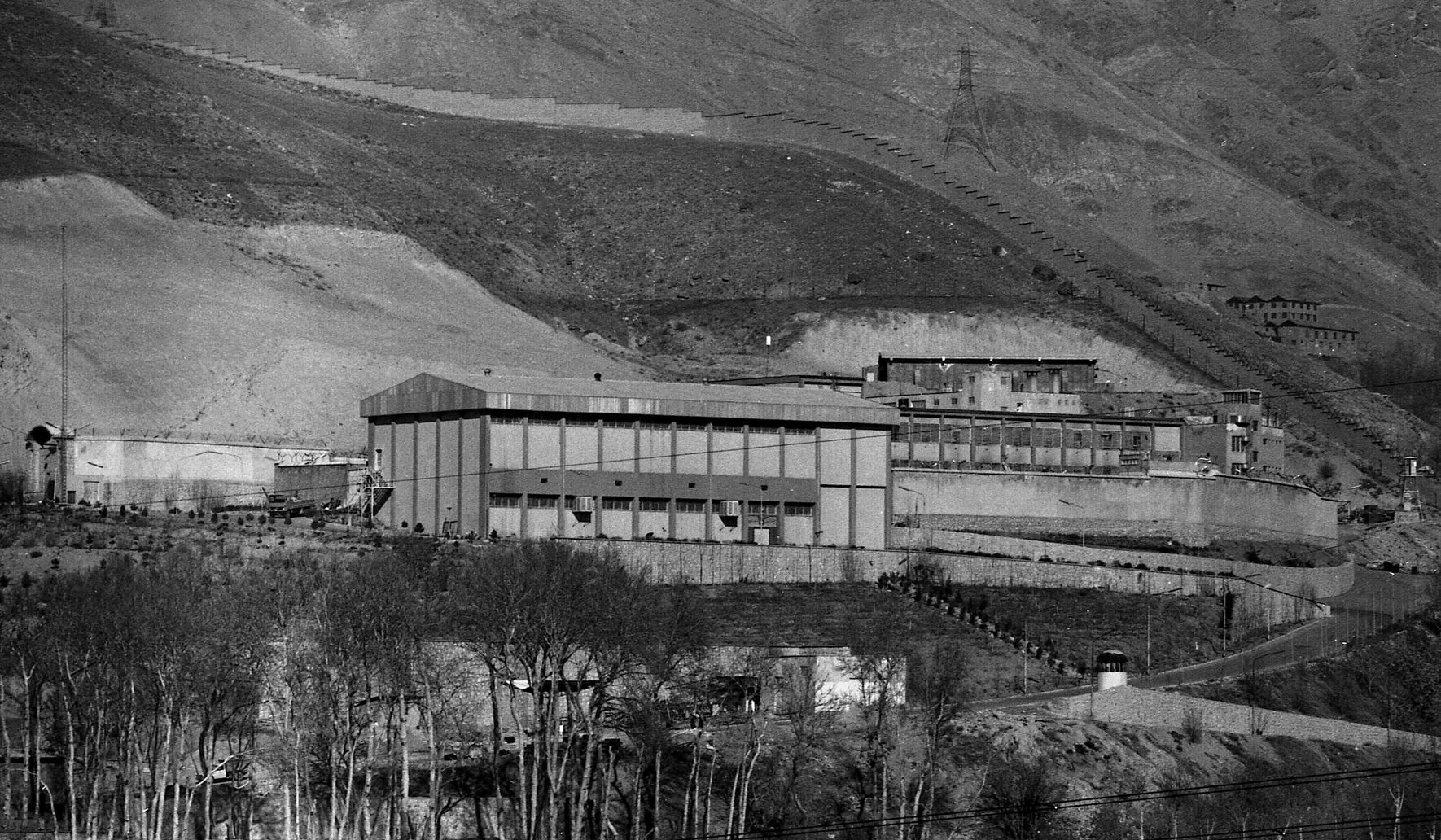

A former Facebook worker imcriminate through the Iranian regime said he had been forced to agree to spy on the West for Iran in order to secure its release. Behdad Esfahbod, who was arrested at the criminal Evin in Tehran in January and left Facebook last month, said he chose not to spy and never informed the social media giant of his dealings with the Iranian government.

“By making it widely public, if you do something to my family, I have the media attention and I’ll start making it public because I think it’s the most productive way for us,” Esfahbod told the Washington Times.

Technology companies, especially social networking sites such as Facebook, are appropriate targets for cyberattacks seeking to tame insiders capable of collecting personal data that provides government secrets or personally identifiable data, such as passwords and accounts, or for blackmail projects.

While Twitter was the victim of a “coordinated social engineering attack” targeting its workers this summer, Esfahbod, an Iranian Canadian software engineer, was preparing to leave Facebook. He said he had to make his detention public to gain an advantage over the Iranian government.

Facebook declined to comment on Esfahbod’s situation, as did the Iranian government, but foreign adversaries who put pressure on generation staff are a new phenomenon.

“Tehran has a habit of targeting Iranians who paint in technical fields,” said Norman Roule, who was Iran’s director of national intelligence from November 2008 to September 2017. “Iranian intelligence facilities are also looking to borrow complex generation from the United States. identifying other Iranian citizens running in the high-tech sector for long-term goals.”

Roule said informants working in social media corporations can provide data on Iranian opposition figures, their supporters and potential funding resources.

Esfahbod said the Iranians had forced him to agree to spy on activists who were running for an open Internet and greater freedoms in Iran, adding teams such as United for Iran in Berkeley, California, the generation organization ASL19 and Small Media in the UK. showed some immediate interest in Esfahbod’s Facebook colleagues, he said.

The Iranians asked Mr. Esfahbod to talk about Mehdi Yahyanejad, co-founder of NetFreedom Pioneers in California, who works to circumvent censorship and provide the Internet to Iranians via satellite television.

Yahyanejad said he lives under constant risk and did not insist that Esfahbod had too many main points on what the Iranians wanted to know. Mr. Yahyanejad said he knew Mr. Esfahbod for about 10 years and was brave. He expressed fear that other Iranians without Esfahbod’s socio-economic prestige might suffer worse luck.

“Part of the fact that he was able to divulge these things is due to the fact that his status, because he is well known, is fine,” Yahyanejad said. “I’m involved in that there are many others who just can’t do those things because they’re not in that position, even if they come out of the closet. Many others might listen to it, and they are simply left to the discretion of the Iranian government, which of course will retaliate.

Esfahbod said he earned a seven-figure salary by executing the restitution of text messages on Facebook before leaving in July, and that he is well known in the generational community. He worked at Google in Canada and California from July 2010 to February 2019 before moving to Facebook in Seattle that month.

Esfahbod said it has made about 10 trips to and from Iran since 2015. Although he was arrested and interrogated in the past, it was the first time he had been imprisoned.

He visited Iran 4 days after Iranian major general Qassem Soleimani was killed near Baghdad International Airport. The airstrike that killed him has raised tensions with the West.

On 8 January, about a week after Soleimani’s death, a Ukrainian advertising plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tehran. Mr. Esfahbod said he arrested him the next day. At the time, U.S. officials said the Iranians shot down the plane. Tehran later admitted that he had done so by accident.

To secure Esfahbod’s cooperation that month, the Iranians threatened to catch him for shooting down the plane, telling him that a circle of family members would lose their jobs, confiscate planes and extract knowledge from their virtual accounts, Esfahbod said.

Documents reviewed through the Washington Times show that Iran confiscated a computer and cell phone and other non-public belongings. Esfahbod said the Iranians downloaded information from their virtual accounts and then showed him pictures of himself with activists at a convention in San Francisco. He said he was gunned down with questions about his relationships and movements abroad.

After Esfahbod agreed to cooperate with Iran in exchange for his release, he said, he went to Portugal to track down his partner, who had warned him that he was opposed to Iran. Esfahbod returned to Seattle in late February, when the coronavirus outbreak made it virtually more unlikely to paint in person.

Suffering from the trauma of his incarceration and aggravated by his bipolar disorder, Esfahbod said he took a low for ill health and that self-isolation caused by coronavirus closures has wreaked havoc. He said he left Facebook in July when he felt unable to work.

Esfahbod stated that he had never been touched or attempted to touch U.S. or Canadian intelligence officials, but that he was willing to cooperate if they sought success in it.

He contacted the news through James Gullis, a spouse of the public relations company Kreab, who said he was helping Esfahbod on behalf of Kreab’s client, Iran International, a Persian media outlet based in London. Iran International’s director of programming is Hossein Rassam, former political analyst leader at the British embassy in Tehran, according to The Telegraph in London.

“We interviewed Behdad, or Iran International interviewed Behdad and knew that when Behdad made the decision to go public, he could pose a threat to his family’s protection or he could simply pose a threat to him since [the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps] has a lot of content that they can use against him when he was extracted from his time in Evin Prison.” Mr. Gullis said. “So we made the decision to help Behdad and draw attention to what is going on and what happened to him in Iran.”

Guy Taylor contributed to this report.