Supported by

Send a story to any friend.

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift pieces to offer per month. Everyone can read what you share.

By James Wagner

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic — Every time she hears that a baseball player in the Dominican Republic tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs, a common occurrence among her compatriots, Jenrry Mejia feels the same intense emotions: sadness and empathy.

Once a more promising young man for the Mets, Mejia, 33, can speak from experience. Major League Baseball and M. L. B. ‘s players’ union agreed to suspensions for violators for the first time since 2005, no player punished more than him: His 3rd positive test, in 2016, triggered a lifetime ban.

Mejia, then in his twenties, recklessly reacted to the punishment and accused M. L. B. of having participation in a conspiracy opposed to him. The lifetime suspension was overturned two years later, after Mejia apologized to MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred for his actions, and was conditionally reinstated. He hasn’t returned to the majors yet.

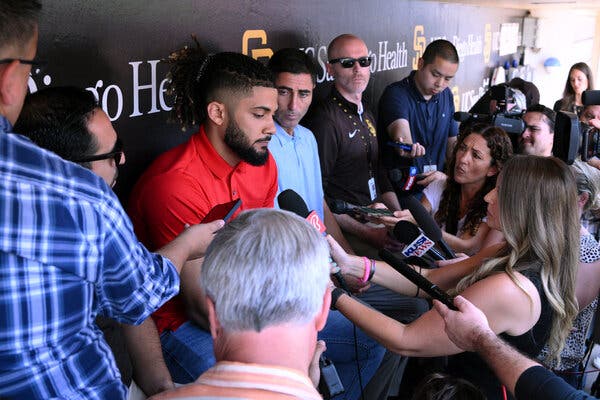

Since then, Mejia has spoken to young players about the risks of steroids and how they derailed his career. So after Fernando Tatis Jr. of the San Diego Padres won an 80-game suspension in August for testing positive for a banned functionality booster, Mejia said he wanted to give Tatis, 23, or any suspended player, some unsolicited advice.

“What he doesn’t want is to have garbage thrown at him,” Mejia said recently in Spanish. “He wants to communicate with him and tell him that everything is going to be okay. Everyone knows that the scenario is bad. But show his face, admit the mistake and move on.

Tatis’ positive check, a shocking occasion due to his prestige as a rising superstar, is just the example of a harrowing phenomenon among players in the Dominican Republic. Since 2005, there have been 1,308 positive cases among primary and minor league players. According to Para M. L. B. , of the 30,000 anti-doping tests carried out in the international season, 0. 2% test positive for performance-enhancing substances, part of which come from players in the Dominican Republic.

For every Robinson Canó, Melky Cabrera and Bartolo Colón who tested positive, many other Dominican minor leaguers were caught. And the most commonly used banned ingredients are outdated anabolic steroids that were prevalent in other sports decades ago.

Dominicans play in every grade of baseball, with 8 in this year’s World Series between the Philadelphia Phillies and Houston Astros. But the percentage of Dominicans who test positive for banned ingredients is disproportionate to their portrayal in the game. Of the 975 players on the 28-player rosters and inactive team rosters this season, 99, just over 10%, came from the Dominican Republic. The percentage is believed to be higher in the minor leagues.

“It’s unfortunate,” Junior Noboa, a former primary league player and national baseball commissioner, said in Spanish in a recent interview from him at Santo Domingo’s Quisqueya Stadium. “It’s unfortunate that after all the discussions and everything that’s been done, they’re still making those mistakes. “

Baseball officials, players, doctors and doping experts have come up with a number of explanations for the positive doping tests.

“A scout looks at your player and if he’s already 16, he’s too old,” said Felix Mena, a personal teacher who began running with Mejia at age 15 and said he runs a drug-free program. 12 years, you have to start making them compete and do things that should not be done. It is the formula that takes away from others. And there is poverty, so it is something social. And you can buy a lot of things without a prescription, like pills and injections. It shouldn’t be like this.

Mena isn’t exaggerating about the age of the players involved. Unlike players in the U. S. In the U. S. or Canada, who are recruited after high school at age 18, or after several years of college, foreign enthusiasts may point to them as loose agents with M. L. B. clubs. 16. But in the race to locate the next big talent, the groups strike verbal agreements with players several years younger than that, creating a frenzied market that critics say breeds corruption and steroid use.

Even after those players have turned pro, Mena said the mentality of excelling at any cost continues. the culture of money hunting. “

The gross national source of income consistent with the capita in the Dominican Republic was about $8,200 last year, according to the World Bank. Because even a modest signing bonus can replace the life of a Dominican family, kids set aside the best school to focus on baseball practice. And when they sign, players have to pay their coaches, who also act as agents, up to 50%.

“In the United States, the player is essentially trained in a school, in a program where there is coverage and guarantees, and there is a draft,” Mejia said. But in the Dominican Republic, when players don’t pitch hard enough in adolescence and don’t get the attention of scouts, Mejia said, they, their parents and coaches are desperate.

“You’re willing to take anything, thinking the banned substance can supposedly help, but it can actually make the scenario worse,” he said, then adding, “Anyone can go to the pharmacy or vet and they’ll sell it to you. “

There is a popular thought in the Dominican Republic that banned ingredients are a quick fix, said Milton Pinedo, a physician and president of Fedomede, the Dominican Federation of Sports Medicine, the framework that administers doping for the country’s Olympic programs, adding that the national baseball team.

“It affects coaches and parents,” Pinedo continued, “who believe that the use of banned ingredients will be a way out of poverty and that other young people will carry it out and point it early. Abnormal confidence in steroids gives them strength they don’t really have. “.

Pinedo indicated two other important points why Dominican professional players end up testing positive more frequently. He pointed to the low levels of schooling in the country, especially among baseball players. As a result, he said, other people “can’t discern or differentiate between what’s true and what’s not” about steroids.

Perhaps the third factor, Pinedo said, perhaps the most important: the country’s lax controls on banned substances, which can be purchased “freely in pharmacies and do not require a prescription. “Even antibiotics can be purchased without a prescription. Older anabolic steroids like stanozolol and boldenone, he said, are popular because they’re readily available.

“These are the ones that were made in the ’80s and have medical uses,” he said. “Other steroids are designer steroids that are more expensive. “

Victor Conte Jr. , the central figure in the BALCO steroid scandal that connected PDG use to some of the country’s most sensible professional baseball, soccer and track athletes, said he believes some baseball players are still bypassing the testing program. But older Dominican drug players are less difficult to catch.

“No one ever used any kind of anabolic steroid like that,” said Conte, who pleaded guilty to distributing steroids and laundering cash in 2005. year. And even in cases like nandrolone, there is one case where 18 months after the injection, it was still detectable.

Pinedo said professional baseball players in the country have tested positive at much higher rates than Olympic athletes. He said the most recent positive result among his foreign athletes in 2019, and that he is a baseball player competing in the Pan American Games.

“There is no political will,” said Pinedo, who urged the Dominican government to adopt stricter restrictions on certain substances. “It’s controlled in many other places. What you sell is not baseball, but you harm the fitness of other young people. And the physical fitness of young people is more important.

Noboa, who is running to reform the country’s player progression system, said he hopes to get legislative approval to get more resources and strength to take on the challenge of doping at a young age, from running with parents to better educating players to punish coaches. in independent academies.

“We have to start with kids from the moment they play in Little League,” Noboa said. anything: ‘It’s just for a while and it will help with an injury,’ they say, ‘No, nothing like that and nothing that’s rarely very much on the approved list. ‘

M. L. B. established a program in the Dominican Republic in 2018 in which running shoes earn a seal of approval from the M. L. B. as long as they allow the league to conduct normal doping tests without warning to their players. This year, the M. L. B. had to perform the highest tests ever conducted in the minor leagues and in the Dominican Republic.

While the M. L. B. se union declined to comment on the matter, the M. L. B. He responded with a statement: “The league has committed really extensive resources, a body of workers and systems to deter DECs in the minor leagues. “

He continued, “As a result of those efforts, in part because of the transparency of the program, the positive test rate among minor league players in the Dominican Republic has been less than 1% for ten consecutive years and has dropped to 85%. from the beginning of the program We will continue and assist our systems in order to strengthen deterrence and safety of players. “

Between playing in the Mexican professional league the normal season and the Toros del Este in the Dominican Winter League, Mejia played with the youngsters Mena is coaching lately. Over the years, Mejia became known and warned them about PD.

Mejia’s tale is a cautionary tale. In April 2015, he suspended 80 games for testing positive for stanozolol. Three months later, he suspended 162 games for testing positive for stanozolol and boldenone. And in February 2016, he won the only permanent suspension in the anti-doping program’s hitale. when boldenone found itself back in your system. He said it was all due to single use; He claimed he didn’t know that some B-12 nutrients he took while having health problems in 2015 had steroids, and that he just stuck in his frame. for so long. Once there, he said it didn’t help him pitch harder.

Intentionally or not, Mejia said everything in his frame was his responsibility, so it was his fault. While one prospect was possibly turning to steroids to win his first professional contract or succeed in the majors, Mejia was already there. He said that the reasons for it at the moment are different. Tatis had already signed a 14-year, $340 million contract when he tested positive, but he was recovering from a wrist injury he suffered in an offseason motorcycle accident.

“Temptations are like, for example, you have pain that you don’t need to admit,” Mejia said. “Or you need to beat it and you think it’s going to help you. Either you need to throw harder or you need to show more. But that’s not the way. Sometimes you don’t mature until you’re 32. Sometimes you think like a child. Why are you for this when you are already at the highest level? »

Mena welcomed closer scrutiny of running shoes across the country and opposed what he called a “bad culture” of parents who see their children as a means of prosperity and drop out of education.

“If our government takes a concrete position on what happens, and if it doesn’t follow the guidelines, they arrest you or fine you,” he said. “It doesn’t matter if you are the father. What is the duty of a 12-year-old boy? Children are not looking for steroids. It is given to them. The government will have to investigate and have a business hand. Coaches want to be controlled and directed and we tell ourselves not to happen and if it does, we are responsible.

Conte, who has continually criticized M. L. B. ‘s checkup program. Since it’s not strict enough, he argues that cheating pays. While suspensions are not paid, he pointed to Cabrera, who was suspended in 2012 for 50 games for a positive check-up and still signed a $16 million contract this winter and then a $42 million contract two years later.

Nelson Cruz, the Washington Nationals’ designated hitter who is widely seen as a leader among the Dominican primary leagues, said it’s encouraging that his compatriots’ positive hit rate has declined.

Cruz, 42, has had his own experience with feature boosters: He suspended 50 games in 2013 over his connection to the Biogenesis scandal in South Florida that ensnared more than a dozen players, adding Ryan Braun and Alex Rodriguez. He praised the education systems in position now that he said they weren’t there when he was younger.

“MLB is doing a wonderful job of giving lectures and recommendations on this, to spare them what’s going on there,” he said recently, later adding, “It’s a process, like everything in life, to have it eliminated forever. This is something that is going to take time, we as Dominicans have to face the truth and we have to prove that.

In the meantime, Mejia said he would continue to pontificate to young people and pray for a momentary possibility in the primary leagues. The closest thing to him returned to spend the 2019 season with the Boston Red Sox Class AAA, but recorded an ERA of 6. 38. .

“I would love to go back to the U. S. , even if it’s for a day,” he said, “so I could say I fell, persevered and made it back to the leagues. “

Advertisment