Smallpox was eliminated in 1980, but I first learned about the turbulent and rich history of the disease in 1996, during an internship at the World Health Organization. When I was a student in the 1990s, I was fascinated by the magnitude of what it would take to eliminate it. a human disease of the earth for the first time.

Over the years, I’ve turned to this story time and time again, for inspiration and guidance to be more ambitious in the face of the public threats of my time to fitness.

In the late 1990s, I had the opportunity to meet some of the fitness professionals and other eradication advocates who helped prevent the disease. I learned that the story of this remarkable achievement had been told primarily through the eyes of white men in the United States. The United States, what later became the Soviet Union, and other parts of Europe.

But I knew there was more to say, and I worried that the stories of legions of local public fitness staff in South Asia would be lost forever. With its dense urban slums, sparse rural villages, complex geopolitics, corrupt governance in some areas, and hostile conditions. In this terrain, South Asia has been the most complicated battleground that smallpox eradicators have had to conquer.

I want to capture some of that history. These paintings have been turned into a podcast, an eight-episode limited-edition audio documentary, titled “Epidemic: Eradicating Smallpox. “

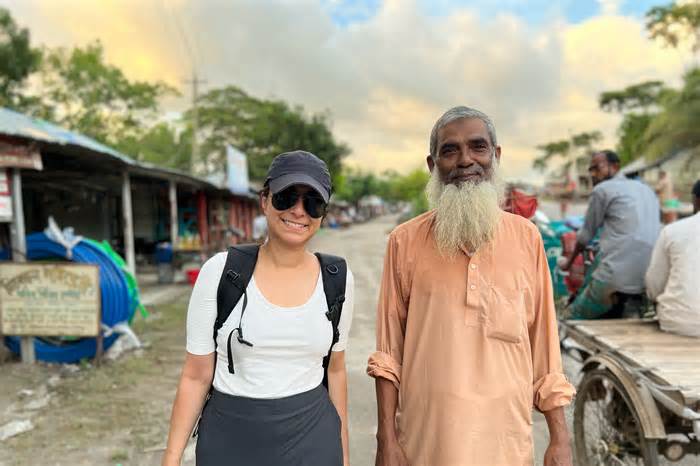

My reporting from the stage began in the summer of 2022, when I visited India and Bangladesh, which had been the scene of a grueling war in the war against the disease. I discovered aging smallpox painters, some now in their 80s and 90s, who had done painstaking work to track down the last case of smallpox in the domain and vaccinate all those exposed. Many veterans of the smallpox crusade had lost contact with others. Their friendships had been forged at a time when long-distance calls were cherished and telegrams were still used for urgent messages.

How did they defeat smallpox? And what kind of victory does this victory have in store for us today?

I also documented the stories of other people who contracted smallpox and survived. What can we learn from this? The survivors I met remind me of my father, who grew up in a rural village in southern India, where his formative years shaped his family circle’s finances that limited access to opportunity. The stories he told me about the wonderful social and economic divisions in India motivated my decision to choose a career in public fitness and working for equity. As we emerge from the Covid pandemic, this connection is an important component of why I wanted to go back in time in search of answers to the demanding situations we face. today.

Unwarranted optimism

I sought out public health workers from India and Bangladesh, as well as epidemiologists from the WHO (largely from the United States and Europe) who had designed and orchestrated eradication campaigns across South Asia. The smallpox leaders of the 1960s and 1970s showed ethical imagination: while many doctors and scientists believed it would be to prevent a disease that had lasted millennia, the champions of eradication had a broader view of the global: not just less smallpox or less smallpox death, but total elimination of the disease. They were not limited to apparent or incremental improvements.

Bill Foege, leader of a crusade in the 1970s, said that, conversely, today’s policymakers can be very reluctant to help systems that don’t yet have the knowledge to back them up. They generally need evidence of sustainability before making an investment in new systems, he said. However, real-world sustainability only becomes transparent when new concepts are put into practice and at scale.

The visionaries of smallpox eradication were another of today’s cautious leaders. “They had unwarranted optimism,” Foege said. They were convinced that perhaps they would accomplish “something that perhaps had not been anticipated. “

In India, in particular, many leaders hoped that their country could compete with other superpowers on the global stage. This idealism partly fueled his confidence that it was possible to stop smallpox.

During the smallpox program in South Asia, Mahendra Dutta was one of the most risk-takers, willing to look beyond the pragmatic and the politically acceptable. He is a physician and public health leader who used his political acumen to help put in place a transformative smallpox vaccination strategy around the world. India.

The eradication crusade has been going on for more than a decade in India. India has invested time and resources – and a lot of exposure – into a mass vaccination approach. But the virus continues to spread uncontrollably. At a time when Indian leaders were keen to prove their strength as a superpower and protect the nation’s symbol on the world stage, Dutta is one of the voices proclaiming to Indian policymakers that mass vaccination does not work.

Dutta told them it was time for India to adopt a new, more targeted vaccination strategy called “vetting and lockdown. “Teams of eradication officials visited communities across India to find active cases of smallpox. user and then vaccinated anyone with whom they had come into contact.

To facilitate the implementation of the new strategy, Dutta asked for favors and even threatened to resign from his position.

He died in 2020, but I spoke to his son Yogesh Parashar, who said Dutta encompasses two worlds: the realities of smallpox eradication and India’s bureaucracy. “My dad did all the dirty work. He also made enemies in the process. “I’m sure, but that’s what he did,” Parashar said.

An inability to meet basic needs

Smallpox control staff have understood the need for buy-in through partnerships: WHO’s Global Smallpox Eradication Programme has paired its epidemiologists with fitness staff from the Indian and Bangladeshi network, bringing together trained lay people and enthusiastic and idealistic medical students. These local smallpox eradication agents were trustworthy. messengers of the public fitness program. They tapped into the region’s myriad cultures and traditions to pave the way for acceptance of the smallpox crusade and triumph over vaccine hesitancy. While they encouraged vaccine uptake, they adopted cultural practices: employing folk songs to spread public messages about fitness. , for example, and honoring how locals used neem leaves to alert others to stay away from the home of a person infected with smallpox.

The eradication of smallpox in South Asia came against a backdrop of natural disasters, civil war, sectarian violence, and famine, crises that created many pressing needs. In many ways, the program has been a success. In fact, smallpox has stopped. However, in efforts to end the virus, public health as a whole has failed to meet people’s fundamental needs, such as shelter or food.

The smallpox control staff I interviewed said they were confronted by local citizens who were transparent about their considerations that, even in the midst of a devastating epidemic, seemed more immediate and vital than smallpox.

Shahidul Haq Khan, an eradication worker, whom podcast listeners meet in episode 4, heard this sentiment while traveling from place to place in southern Bangladesh. People would ask him, “There’s no rice in people’s stomachs, so what’s a vaccine going to do?He said.

But the eradication project didn’t come with the immediate assembly needs, so the fitness staff had their hands tied.

When a network’s immediate considerations aren’t addressed through public fitness, it can look like contempt, and it’s a mistake that damages the reputation and long-term effectiveness of public fitness. When public fitness officials return to a network years or decades later, the memory of this can make it even more difficult to mobilize the cooperation needed to respond to long-term public health crises.

Rahima Banu is left behind

The eradication of smallpox was one of humanity’s greatest triumphs, but many other people (even the greatest example of that victory) did not participate in that victory. Understanding this struck me a lot when I met Rahima Banu. As a child, she was the last user. It is known around the world that he contracted a natural case of severe smallpox. As a child, she and her family had, for a time, unprecedented access to the care and attention of public fitness professionals struggling to combat smallpox.

But this concentrate did not stabilize the family in the long run or lift them out of poverty.

The Banu have become a symbol of the eradication effort, but they did not share the prestige and awards that followed. Nearly 50 years later, Banu, her husband, three daughters and a son share a one-room space made of bamboo and corrugated cardboard. iron with dirt floor. Their finances are precarious. The family can’t take care of their physical health or send their daughter to college. In recent years, when Banu has had health or vision problems, no public health employee has rushed to help him.

“I can’t thread a needle because I can’t see clearly. I can’t read about lice on my child’s head. I can’t read the Quran well because of my vision,” Banu said in Bengali, through a translator. “You don’t have to know how I live my life with my husband and children, if I’m healthy or not, if I’m settled in my life or not. “

Missed Opportunities

I believe that some of our public fitness efforts today are repeating the mistakes of the smallpox eradication campaign, failing to meet people’s fundamental desires and lacking the opportunity to use the existing crisis or epidemic to make lasting innovations in overall fitness.

The 2022 fight against mpox is a case in point. The highly contagious virus spread around the world and spread rapidly, mostly among men who have sex with men. In New York, for example, in part because some blacks and Hispanics had an old Because of distrust of city officials, those teams ended up with lower Mpox vaccination rates. And this failure in vaccination has missed an opportunity to provide education and other fitness treatments, adding access to HIV testing and prevention.

And the same thing happened with the pandemic Covid. Se have mobilized health care providers, clergy, and leaders of communities of color to announce vaccination. These trusted messengers have been successful in reducing racial disparities in vaccination coverage, protecting not only their own, but also protecting hospitals from overwhelming patient numbers. Many were not paid to do this work. They intervened even though they had clever explanations for why they were suspicious of the health care system. In some ways, government officials have maintained their end of the social contract, providing social and economic relief to those communities during the pandemic.

But now we’re back to normal, with a growing lack of confidence in finances, housing, food, physical care, and health care in the United States. The acceptance as true that has been built with those communities is eroding again. The form of preoccupation with unfulfilled fundamental desires deprives us of our ability to believe bigger and better. Our lack of trust in immediate desires, such as physical attention and the provision of care, erodes acceptance as true in government, in other institutions, and in everyone else. , leaving us less prepared for the next public health crisis.

This article was produced through KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism on fitness issues and is one of KFF’s primary operating systems – the independent source for research, surveys, and journalism on fitness policy.

Share this story:

Smallpox was eliminated in 1980, but I first learned about the turbulent and rich history of the disease in 1996, during an internship at the World Health Organization. When I was a student in the 1990s, I was fascinated by the magnitude of what it would take to eliminate it. a human disease of the earth for the first time.

Over the years, I’ve turned to this story time and time again, for inspiration and guidance to be more ambitious in the face of the public threats of my time to fitness.

In the late 1990s, I had the opportunity to meet some of the fitness professionals and other eradication advocates who helped prevent the disease. I learned that the story of this remarkable achievement had been told primarily through the eyes of white men in the United States. The United States, what later became the Soviet Union, and other parts of Europe.

But I knew there was more to say, and I worried that the stories of legions of local public fitness staff in South Asia would be lost forever. With its dense urban slums, sparse rural villages, complex geopolitics, corrupt governance in some areas, and hostile conditions. In this terrain, South Asia has been the most complicated battleground that smallpox eradicators have had to conquer.

I want to capture some of that history. These paintings have been turned into a podcast, an eight-episode limited-edition audio documentary, titled “Epidemic: Eradicating Smallpox. “

My reporting from the stage began in the summer of 2022, when I visited India and Bangladesh, which had been the scene of a grueling war in the war against the disease. I discovered aging smallpox painters, some now in their 80s and 90s, who had done painstaking work to track down the last case of smallpox in the domain and vaccinate all those exposed. Many veterans of the smallpox crusade had lost contact with others. Their friendships had been forged at a time when long-distance calls were cherished and telegrams were still used for urgent messages.

How did they defeat smallpox? And what kind of victory does this victory have in store for us today?

I also documented the stories of other people who contracted smallpox and survived. What can we learn from this? The survivors I met remind me of my father, who grew up in a rural village in southern India, where his formative years shaped his family circle’s finances that limited access to opportunity. The stories he told me about the wonderful social and economic divisions in India motivated my decision to choose a career in public fitness and working for equity. As we emerge from the Covid pandemic, this connection is an important component of why I wanted to go back in time in search of answers to the demanding situations we face. today.

Unwarranted optimism

I sought out public health workers from India and Bangladesh, as well as epidemiologists from the WHO (largely from the United States and Europe) who had designed and orchestrated eradication campaigns across South Asia. The smallpox leaders of the 1960s and 1970s showed ethical imagination: while many doctors and scientists believed it would be to prevent a disease that had lasted millennia, the champions of eradication had a broader view of the global: not just less smallpox or less smallpox death, but total elimination of the disease. They were not limited to apparent or incremental improvements.

Bill Foege, leader of a crusade in the 1970s, said that, conversely, today’s policymakers can be very reluctant to help systems that don’t yet have the knowledge to back them up. They generally need evidence of sustainability before making an investment in new systems, he said. However, real-world sustainability only becomes transparent when new concepts are put into practice and at scale.

The visionaries of smallpox eradication were another of today’s cautious leaders. “They had unwarranted optimism,” Foege said. They were convinced that perhaps they would achieve “something that perhaps had not been foreseen. “

In India, in particular, many leaders hoped that their country could compete with other superpowers on the global stage. This idealism partly fueled his confidence that it was possible to stop smallpox.

During the smallpox program in South Asia, Mahendra Dutta was one of the most risk-takers, willing to look beyond the pragmatic and the politically acceptable. He is a physician and public health leader who used his political acumen to help put in place a transformative smallpox vaccination strategy around the world. India.

The eradication crusade has been going on for more than a decade in India. India has invested time and resources – and a lot of exposure – into a mass vaccination approach. But the virus continues to spread uncontrollably. At a time when Indian leaders were keen to prove their strength as a superpower and protect the nation’s symbol on the world stage, Dutta is one of the voices proclaiming to Indian policymakers that mass vaccination does not work.

Dutta told them it was time for India to adopt a new, more targeted vaccination strategy called “vetting and lockdown. “Teams of eradication officials visited communities across India to find active cases of smallpox. user and then vaccinate anyone they have come into contact with.

To facilitate the implementation of the new strategy, Dutta asked for favors and even threatened to resign from his position.

He died in 2020, but I spoke to his son Yogesh Parashar, who said Dutta encompasses two worlds: the realities of smallpox eradication and India’s bureaucracy. “My dad did all the dirty work. He also made enemies in the process. ” I’m sure, but that’s what he did,” Parashar said.

An inability to meet basic needs

Smallpox control staff have understood the need for buy-in through partnerships: WHO’s Global Smallpox Eradication Programme has paired its epidemiologists with fitness staff from the Indian and Bangladeshi network, bringing together trained lay people and enthusiastic and idealistic medical students. These local smallpox eradication agents were trustworthy. messengers of the public fitness program. They tapped into the region’s myriad cultures and traditions to pave the way for acceptance of the smallpox crusade and triumph over vaccine hesitancy. While they encouraged vaccine uptake, they adopted cultural practices: employing folk songs to spread public messages about fitness. , for example, and honoring how locals used neem leaves to alert others to stay away from the home of a person infected with smallpox.

The eradication of smallpox in South Asia came against a backdrop of natural disasters, civil war, sectarian violence, and famine, crises that created many pressing needs. In many ways, the program has been a success. In fact, smallpox has stopped. However, in efforts to end the virus, public health as a whole has failed to meet people’s fundamental needs, such as shelter or food.

The smallpox control staff I interviewed said they were confronted by local citizens who were transparent about their considerations that, even in the midst of a devastating epidemic, seemed more immediate and vital than smallpox.

Shahidul Haq Khan, an eradication worker, whom podcast listeners meet in episode 4, heard this sentiment while traveling from network to network in southern Bangladesh. People would ask him, “There’s no rice in people’s stomachs, so what’s a vaccine going to do?”? He said.

But the eradication project didn’t come with the immediate assembly needs, so the fitness staff had their hands tied.

When a network’s immediate considerations aren’t addressed through public fitness, it can look like contempt, and it’s a mistake that damages the reputation and long-term effectiveness of public fitness. When public fitness officials return to a network years or decades later, the memory of this can make it even more difficult to mobilize the cooperation needed to respond to long-term public health crises.

Rahima Banu is left behind

The eradication of smallpox was one of humanity’s greatest triumphs, but many other people (even the greatest example of that victory) did not participate in that victory. Understanding this struck me a lot when I met Rahima Banu. As a child, she was the last user. It is known around the world that he contracted a natural case of severe smallpox. As a child, she and her family had, for a time, unprecedented access to the care and attention of public fitness professionals struggling to combat smallpox.

But this concentrate did not stabilize the family in the long run or lift them out of poverty.

The Banu have become a symbol of the eradication effort, but they did not share the prestige and awards that followed. Nearly 50 years later, Banu, her husband, three daughters and a son share a one-room space made of bamboo and corrugated cardboard. iron with dirt floor. Their finances are precarious. The family can’t take care of their physical health or send their daughter to college. In recent years, when Banu has had health or vision problems, no public health employee has rushed to help him.

“I can’t thread a needle because I can’t see clearly. I can’t read about lice on my child’s head. I can’t read the Quran well because of my vision,” Banu said in Bengali, through a translator. “You don’t have to know how I live my life with my husband and children, if I’m healthy or not, if I’m settled in my life or not. “

Missed Opportunities

I believe that some of our public fitness efforts today are repeating the mistakes of the smallpox eradication campaign, failing to meet people’s fundamental desires and lacking the opportunity to use the existing crisis or epidemic to make lasting innovations in overall fitness.

The 2022 fight against mpox is a case in point. The highly contagious virus spread around the world and spread rapidly, mostly among men who have sex with men. In New York, for example, in part because some blacks and Hispanics had an old Because of distrust of city officials, those teams ended up with lower Mpox vaccination rates. And this failure in vaccination has missed an opportunity to provide education and other fitness treatments, adding access to HIV testing and prevention.

And the same thing happened with the pandemic Covid. Se have mobilized health care providers, clergy, and leaders of communities of color to announce vaccination. These trusted messengers have been successful in reducing racial disparities in vaccination coverage, protecting not only their own, but also protecting hospitals from overwhelming patient numbers. Many were not paid to do this work. They intervened even though they had clever explanations for why they were suspicious of the health care system. In some ways, government officials have maintained their end of the social contract, providing social and economic relief to those communities during the pandemic.

But now we’re back to normal, with a growing lack of confidence in finances, housing, food, physical care, and health care in the United States. The acceptance as true that has been built with those communities is eroding again. The form of preoccupation with unfulfilled fundamental desires deprives us of our ability to believe bigger and better. Our lack of trust in immediate desires, such as physical attention and the provision of care, erodes acceptance as true in government, in other institutions, and in everyone else. , leaving us less prepared for the next public health crisis.

This article was produced through KFF Health News, a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism on fitness issues and is one of KFF’s primary operating systems – the independent source for research, surveys, and journalism on fitness policy.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism on fitness issues and is one of the main operating systems of KFF, an independent journalism of research, polling and fitness policies. Learn more about KFF.

This story can be republished for free (details).

We inspire organizations to republish our content for free. Here’s what we’re asking:

You will need to credit us as the original publisher, with a link to our site californiahealthline. org. If possible, include the original authors and “California Healthline” in the signature. Keep the links in the story.

It’s critical to note that not everything that appears on californiahealthline. org is available for republication. If an article has the tag “All Rights Reserved”, we cannot grant permission to republish that article.