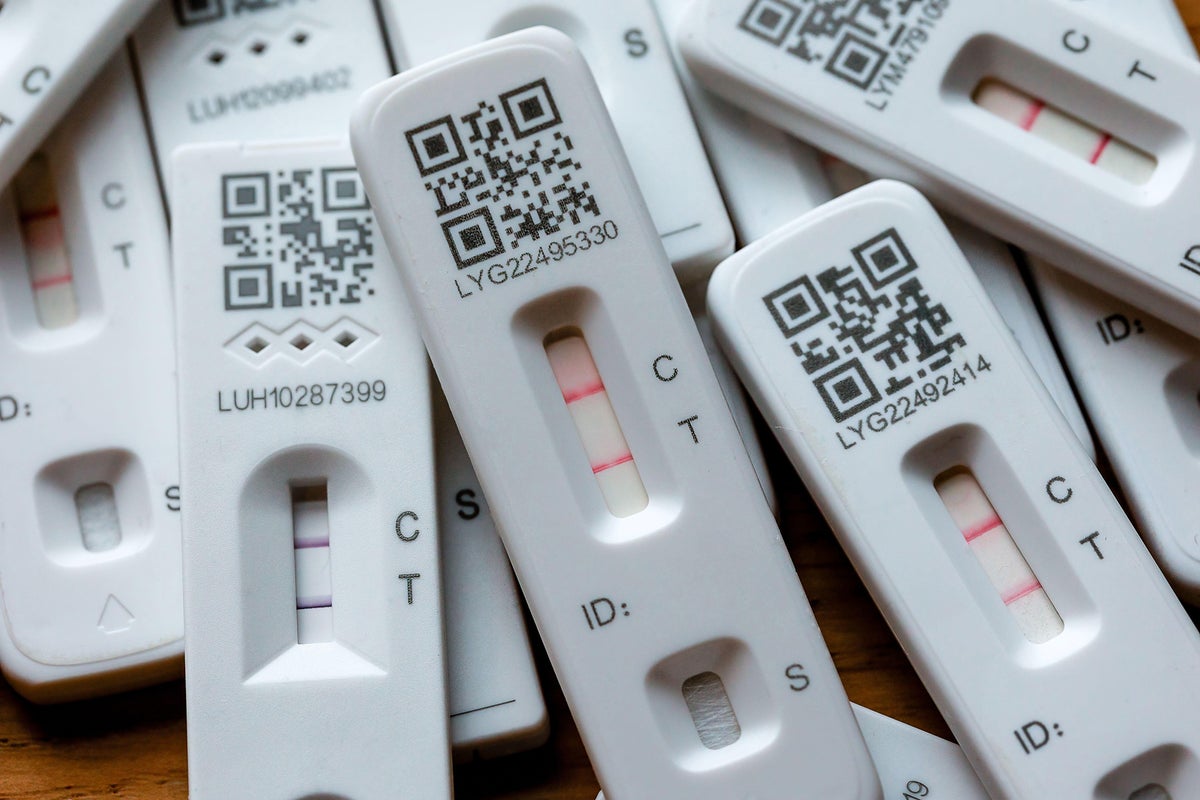

The colors of the lines on COVID tests can imply that you are healthy or still sick, if interpreted correctly.

By Sam Jones

Milton Cogheil/Alay Stock Photo

As others attend indoor gatherings and prepare for the winter holidays, COVID cases in the U. S. have increased over the past month. This is not surprising: In the first three years of the pandemic, cases increased in the weeks after Thanksgiving. and in the new year.

So, on those days, many other people take COVID antigen tests at home and look for the pink line in the testing window that indicates if they are infected. But this line can vary in intensity, from strong to weak. Let’s just say that those color adjustments can give you more than a “virus” or “non-virus” reaction by telling you whether your disease is getting worse or worse, and thus revealing whether or not it passes to a family. your future soon.

However, that’s not how those tests were designed. “I think it’s human nature to look at the intensity of the tapes and say, ‘Oh my God, it looks like I’m positive and maybe there’s more virus out there. ‘” says Paul Drain, a physician and infectious disease researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle. But, he says, it’s vital not to forget that those tests didn’t evolve to be quantitative, meaning they can’t officially say how much virus is in the sample. They are also not allowed to do so through the Food and Drug Administration.

Yet “it’s not a binary yes or no,” says physician and immunologist Michael Mina, chief science officer at eMed Digital Healthcare. Mina spearheaded large-scale COVID testing programs while at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University at the start of the pandemic and for years worked on the development of next-generation immunological tools to aid in public health surveillance. “It’s a part of the basic chemistry of how these tests work to be semiquantitative.” The tests use antibodies, immune system proteins, that react to specific proteins—called antigens—that are part of the COVID-causing virus SARS-CoV-2. The line that you see on a test “is actually made up of millions and millions of little antibodies holding onto a dye,” Mina says, and the only reason those antibodies are able to stick to the line is that they’re also stuck to the virus antigens. “So the more virus, the more little dye molecules are going to line up on the line,” Mina says.

“In the paintings we’ve done, and others that have looked at this, the intensity of the line tends to correlate with the amount of antigen in the sample,” says Morgan Greenleaf, an engineer at Emory University School of Medicine. Greenleaf is also director of variant operations at Atlanta’s Microsystems Engineering Point-of-Care Technologies Center, one of the sites where corporations send antigen tests to validate their functionality against new SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Although antigen tests are not, by any means, the only way to determine illness and help keep people from spreading COVID to others, Mina says, “they’re our way to see what’s otherwise invisible to us.” And he believes that that visual signal, and the idea that band intensity correlates with the level of virus, provides people with a tool for monitoring the course of their infection.

But, he says, this tool only works if you have at least a few checks. Think about what will happen if you just do a check and show a slight line. “So you’re in this weird purgatory,” Mina says. The line may simply mean that you are at the very birth of an infection and the virus is being born to accumulate in your body. Or it may simply mean you’re at the end and your immune formula has almost eliminated the microbe. . So, you may be about to get sicker or almost virus-free.

The key is to be able to see the direction of the color change within a few days. If you check and see a dark band, and then check again a few days later and see a lighter band, “you can give a sigh of, “Okay, my body is doing its job. This eliminates this virus. My immune formula is working,” says Mina. Conversely, if you have symptoms and “see very positive effects for a week,” he says, you may need to see your doctor. The antiviral Paxlovid could help and be taken within five days of the onset of symptoms.

Mina also says that COVID antigen tests shouldn’t be used to completely alter your usual behavior—unless, of course, the test is positive. For instance, if you typically mask at large gatherings, you should continue to mask even if you get a negative result. And, he says, “if you’re positive, don’t go at all.” If you test positive, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says to stay home for at least five days and then, regardless of severity, wear a mask through day 10 of symptom onset or until you have two negative antigen tests 48 hours apart.

Drain says other people also deserve to be careful not to overinterpret test results. For example, “someone can have severe respiratory distress and still have a very low positive line,” Drain says. In some cases, even if there is little virus left in a person’s body, it faces potentially harmful consequences similar to fluid buildup in their lungs. “We don’t need to give other people the impression that if your symptoms are severe but your line is very weak, it’s a mild infection and you’re safe. “

Human error—for example, superficial swabbing that picks up little virus when a more careful swab would collect much more—is another important caveat to how much you can learn by looking at the band intensity, says physician Apurv Soni, who studies home testing. (Soni likens home antigen testing to making a cup of espresso: How a person does it affects the results. The amount of beans loaded, time the machine runs or amount of force applied when tamping down the grounds could all vary from one person to the next.)

Mina is a bit less worried about user error with swabbing except in cases where someone is right at the border of being able to see a line or not. “Maybe it can push somebody into negative territory if they’ve done a really poor job swabbing,” he says. But the tests show a positive band when there are only a relatively skimpy hundreds of thousands of viral particles per milliliter of sample. If you have a billion viral particles per milliliter—which is not unusual in the middle of an infection—you can miss 99 percent of them with a swab, and there would still be 10 million viral particles on the swab end, he says, which would show up as a very dark line.

Still, if you’re comparing levels on other days, avoid switching checkmarks if possible, Greenleaf says. This is because there may be some variability in the limit of detection (LOD), the smallest amount of virus that can be detected, between controls, as well as in how LOD is measured, which may simply be color intensity.

While buying many of those tests without a prescription can be expensive, depending on your insurance, the U. S. government will not be able to buy them. UU. se has proposed sending some free tests to the public by the end of last fall. Some public fitness centers, in addition to those funded through the Health Resources and Services Administration, are making free or affordable COVID testing for uninsured people or members of underserved communities. Another opportunity for underserved teams is the National Institutes of Health’s Home Test to Treat telefitness program, which offers free at-home COVID and flu tests. to others who are not positive for those conditions at the time of enrollment. (For others who are already sick, the program offers treatment options. )

The positive effects of at-home controls cause anxiety and fear. But when used correctly, lines can also make meeting scheduling safer and easier.

Learn about and share the most interesting discoveries, innovations and concepts that shape our world today.

Follow:

Scientific American is part of Springer Nature, which owns or has commercial relations with thousands of scientific publications (many of them can be found at www.springernature.com/us). Scientific American maintains a strict policy of editorial independence in reporting developments in science to our readers.

© 2023 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, A DIVISION OF SPRINGER NATURE AMERICA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.