ad

Supported by

Guest essay

Send a story to any friend.

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift pieces to offer per month. Everyone can read what you share.

By Ezekiel J. Emanuel and Matthew Guido

Dr. Emanuel is a physician and vice chancellor for global projects and professor of medical ethics and fitness policy at the University of Pennsylvania. Guido is an assistant to Dr. Emanuel.

Twenty-three years ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention declared that measles had been eliminated in the United States. Last month, the CCC joined the World Health Organization in warning that the disease, which vaccines can prevent, had “an imminent risk in each and every region of the world. “

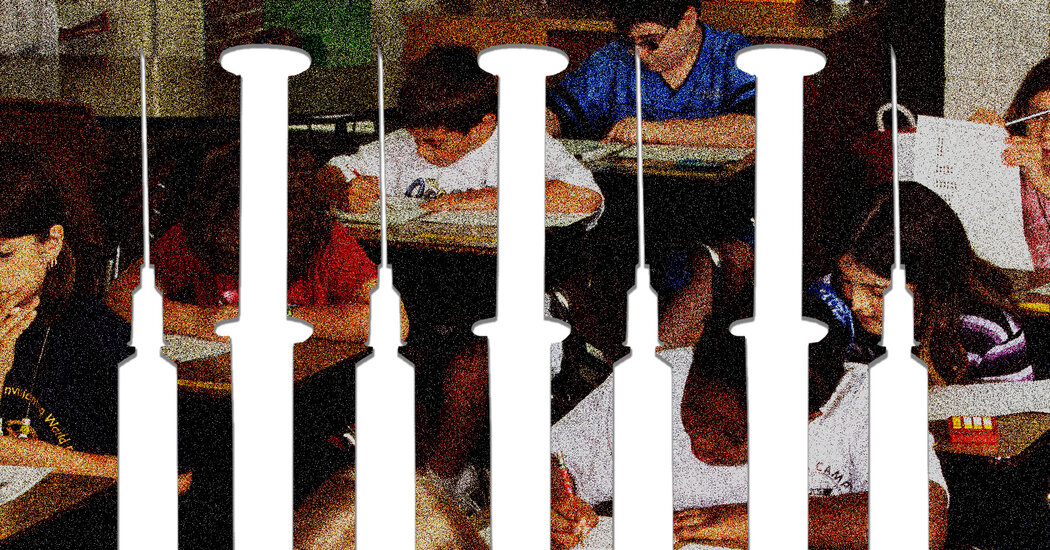

What happened? Vaccination rates for children have declined since the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic. In recent weeks, fitness officials in and around Columbus, Ohio, have battled a measles outbreak, with more than 70 cases reported in unvaccinated children and none in fully vaccinated children. young people. As a polio resurgence in July in Rockland County, north of New York City, made clear, this is just a measles problem.

Routine immunization rates in the formative years in the United States have been among the most productive in the world. But in the first year of the pandemic, the country’s youth did not receive nine million doses of vaccines against diseases such as polio and measles. vaccines for the formative years: for measles, mumps and rubella; chickenpox; and diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis, fell by an average of 1. 3 percentage points, with rates in seven states and many cities below 90%.

What do those numbers mean in terms of the spread of the disease?For measles, for example, the decline is significant because of its herd immunity threshold. If the proportion of the immunized population opposed to the disease is above the measles threshold, the spread of the disease will decrease. For measles, the threshold is estimated at 95%. For the 2020-2021 school year, the vaccination rate for kindergarten students is 93. 9%, below the threshold. Measles will likely continue to spread at most.

Measles should not be taken lightly. The virus is highly contagious; According to the CDC, if a user has it, up to 90% of people close to that user who are not immune will also become infected. It can live up to two hours in the air. One to three out of every 1,000 children who contract measles die from respiratory and neurological complications.

Early knowledge suggests that policy rates continue to decline. For example, Colorado’s vaccination rates among kindergarteners dropped by 5. 2 percentage points from the 2020-21 school year.

Recent declines in EE. UU. se have largely been attributed to disruptions in public gyms caused by the pandemic. But this explanation is largely incorrect. The decline also appears to be a result of explicit, interstate policies, policies that can lead to a more sustained decline in vaccination rates.

International comparisons suggest that the emergence of the pandemic and declining vaccination rates of the regimen are not inevitable. Over the past three years, the proportion of children who received three doses of the vaccine that protects against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis has consistently remained at the top. in France, Germany, Switzerland, Israel and Australia, and Canada and Norway. The decline in measles vaccines in Europe is mainly in the war zone of Ukraine and other parts of Eastern Europe.

Now let’s take a look at what’s in the United States.

The state with the highest immunization rate in formative years is not Massachusetts, Vermont, or the high-income, high-knowledge blue state with smart public fitness infrastructure and smart fitness outcomes. This is Mississippi, a dark red state with the third-lowest Covid vaccination rate among states. Mississippi also consistently ranks as the worst or time among states for many other key public health measures, adding infant mortality and overall life expectancy. However, about 99 percent of Mississippi children are vaccinated during the first three years of training. Vaccines.

On the other hand, Colorado and Maryland, consistently ranked among the states with the most productive fitness systems, reported immunization rates in formative years roughly equal to or less than 90% for the 2020-21 school year, the most recent year for which CDCData for all states is available. Colorado’s measles, mumps and rubella rate is 90. 5% and Maryland’s is 87. 6%, either in the back quarter of the states.

Surprisingly, in line with perhaps, the immunization rate in the formative years in the nation’s capital is a dismal 78. 9% against measles, mumps and rubella, dangerously below the point at which the spread of the virus will begin to slow, and the polio vaccination rate is 80 consistent with percent. necessarily to the threshold of herd immunity of the disease.

The acceptance of the Covid vaccine and anti-vaccine attitudes do not completely eliminate the differences between states. Neither the red-blue party affiliations nor the strength of a state’s public fitness system. Instead, the decline is rooted in some states’ longstanding policies that allow, for example, non-medical exemptions, inability to rigorously enforce vaccination requirements, and insufficient public fitness campaigns.

This is how the decline can be reversed.

States deserve to eliminate non-medical exemptions. Five of the six states that prohibit those exemptions were well above the national average for vaccination rates in the 2020-21 school year. (The sixth, West Virginia, did not report its vaccination rates in the last year on record. )They have a The effect of banning non-medical exemptions is well documented. After a measles outbreak began in 2014-2015 at Disneyland, California’s legislature and governor passed a law that eliminated non-medical exemptions.

The result: a 3. 3 percentage point increase in measles, mumps and rubella vaccination rates, putting the state above the measles immunity threshold. In contrast, Idaho, Arizona, Oregon and Wisconsin had the highest exemption rates in 2020-2021 and had vaccination rates below the national average for measles, mumps and rubella and for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis.

States also deserve to end extensions for school-age children to introduce the pandemic vaccine regimen and adopt vigorous awareness campaigns and networked education to inspire vaccines by emphasizing their protection and importance. With the pandemic and staff shortages, many schools have had less time for full vaccination testing. or touch parents about the lack of documents. States will need to provide mandatory remedies to ensure compliance.

Children 14 and older deserve to be allowed to download all polio, measles, and other recommended vaccines for missed formative years without parental permission. In many states, there are precedents for adolescent consent for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases and psychiatric care.

Finally, states deserve to embrace the technology updates and knowledge standardization needed to link knowledge between schools, local and state immunization programs, and immunization rates from the formative years of CDC’s monitoring regime. School nurses can use this knowledge to read about students’ vaccination status. Currently, there is a gap of about two years in federal knowledge about vaccination rates among kindergarten children.

Vaccines are one of the few real savings in medicine. Routine vaccines for children born between 1994 and 2018 are expected to save you nearly a million premature deaths and save about $1. 9 trillion in economic costs, or more than $5,700 for both Americans, according to the CDC. For measles, a state can spend more than $2 million to respond to a single outbreak, with an average cost of about $50,000, according to a study of a recent outbreak in Washington state.

To avoid harmful and costly epidemics, states introduce viable responses that provide their youth and communities with the best protections against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel (@ZekeEmanuel) is a physician and vice chancellor for global projects and professor of medical ethics and fitness policy at the University of Pennsylvania. Matthew Guido is an assistant to Dr. Emanuel.

The Times is committed to publishing a series of letters to the editor. We’d love to hear what you think of this article or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here is our email: lettres@nytimes. com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

ad