The effects of the review highlight major disparities in geographic access to these remedies, which disproportionately affect rural, American Indian, and Alaska Native communities. The effects are published in JAMA Network Open.

“There are transparent disparities in spatial access to testing sites to treat, that is, in several communities that have experienced worse outcomes during the pandemic,” said lead author Rohan Khazanchi, MD, MPH, a resident of Brigham’s Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Residency Program. These findings challenge us to read about the opportunities that exist for the strategic location of test sites to address closer to communities that may most desire this program. “

These studies extend from the Biden administration’s March 2022 announcement of the Test to Treat initiative, a public fitness program that introduced a place where other people can get a COVID-19 test, communicate with a doctor, get an antiviral prescription, and fill their prescription.

While the Test to Treat initiative aims to build for care, this study suggests that geography can play an important role in achieving equity.

“Paxlovid is an oral antiviral that would possibly reduce the risk of hospitalization or death in other people with COVID-19 who have key risk points such as complex age, not being vaccinated or up-to-date on COVID-19 vaccines, or having one or more medical situations at risk,” said leader Kathleen McManus, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine in UVA Health’s Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health.

“In particular, those threat points are disproportionately prevalent among rural and minority communities, some of which, as our study found, might have the lowest geographic access to the Paxlovid remedy through testing sites to treat. “

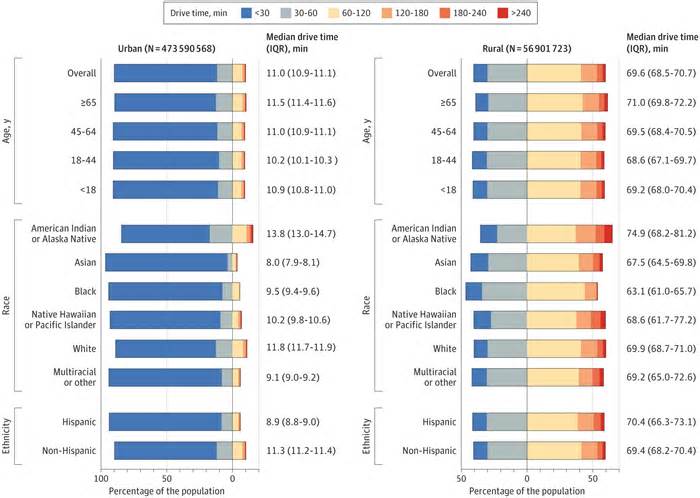

The researchers analyzed the published geographic locations of 2,227 dedicated testing sites to treat COVID-19 on the healthdata. gov website, indexed as of May 4, 2022. They then calculated the shortest time required from the population center of each of the census tracts to succeed at one of the ten geographically closest sites. Finally, they connected the demographics of the census tract with the driving distances calculated to calculate the national proportions of each of the demographic subgroups living within a safe driving distance of each of the sites.

Its effect is that 15% of the U. S. population is in the U. S. In the U. S. , 59% of rural citizens lived more than a 60-minute drive from the nearest Test to Treat site. Greater disaggregation by age and race/ethnicity indicates that 17% of seniors, 30% of American Indians and Alaska Natives, 17% of whites, 8% of Hispanics and 8% of blacks lived in more than 60 minutes. of the nearest site.

Native American and Alaska Native populations had longer driving times after accounting for rurality, suggesting they are only far removed from access to antivirals despite carrying a disproportionate COVID-19 burden.

The researchers also found that Asian, black and Hispanic populations live closer to test sites to treat on average than white, American Native or Alaska Native populations, suggesting that those populations had greater geographic access. not necessarily a sign of fairness, given the transparent national knowledge that it appears those same populations are even less likely to receive outpatient treatment for COVID-19 compared to white people.

“I think this goes in the direction of a broader point that, to achieve equity, hitting just one right website doesn’t automatically solve access to care disruptions,” Khazanchi said. “There’s still intentional education, awareness and communication that you want to do based on that to build buy-in in underserved communities and make sure the drugs succeed in the other people who need them most. “

“This is the moment in our team examining the geographic accessibility of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic,” McManus said.

“Our first review [in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in 2021] looked at geographic access to COVID-19 biomedical cure clinical trials and we discovered a similar problem: geographic accessibility for subpopulations did not translate into representation in clinical trials. Black and Other Hispanics were underrepresented in COVID-19 cure trials, which was surprising given their relative geographic proximity to trial sites and disproportionate COVID-19 hospitalization rates.

While measuring driving time presented researchers with a concrete tool for assessing an individual’s proximity to test sites to treat, Khazanchi posits that driving time is not a universal measure of access. He explains that in urban areas, where many other people rely on public transportation or possibly wouldn’t own a vehicle, measuring spatial accessibility becomes much more complicated.

As COVID-19 disparities persist and new and existing variants multiply, researchers continue to explore how to promote fitness equity across multiple dimensions, with the common purpose of providing testing and remedies to those who need it most. An example of this can be discovered in the paintings being done at Mass General Brigham, where information from the Community Care Vans initiative has demonstrated the effectiveness of bringing COVID-19 fitness facilities to where others need them most.

Please indicate the appropriate maximum category to facilitate the processing of your request

Thank you for taking the time to provide feedback to the editors.

Your opinion is for us. However, we do not guarantee individual responses due to the large volume of messages.