Advertisement

Supported by

In the United Arab Emirates, a program is developing local corals from the Persian Gulf that have evolved to withstand maximum temperatures.

By Jenny Gross

Reporting from Dubai and Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates

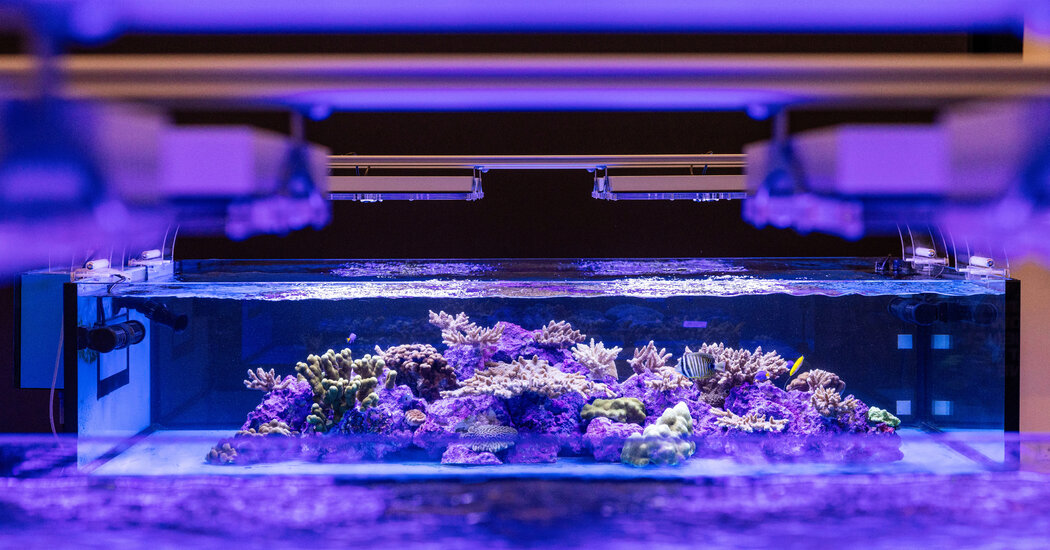

Not from where the superyachts are docked in Dubai’s marina, but in a laboratory some 1,000 pieces of coral, cut a month ago, are grown in four aquariums.

A land-based laboratory in the Arabian Desert may seem like an unlikely spot for regenerating coral reefs. But, already, the corals are brighter than when they were cut in mid-November.

“We can start to see the sign that coral is slowly starting to grow from above,” said Ahmed Hamdy, director of a coral farm. In six to 12 months, when the corals are healthy enough, Coral Vita, a private company that is engaged in reef restoration, will move them to waters outside Dubai.

It’s part of an experiment. Coral recovery systems face long-standing challenges due to climate changes and environmental degradation, but marine scientists say they are key to ensuring some coral species don’t go extinct. And corals in the Persian Gulf have evolved to withstand maximum temperatures. , making them one of the most productive applicants for understanding how reefs respond to excessive heat.

At the United Nations meteorological summit in Dubai, negotiations focused less on the global biodiversity crisis and more on reaching an agreement to reduce fossil fuel production. But healthy ecosystems, in addition to nourishing plants and animals, are imperative for storing carbon. and protective costs.

Coral reefs occupy less than 0. 1% of the ocean floor, but 25% of all known marine species have them at some point in their life cycle. What’s more, “they stop typhoon surgees in their tracks,” said Tali Vardi, executive director. of the Coral Restoration Consortium, an organization committed to supporting coral recovery professionals. This is especially because global warming increases the intensity of typhoons, he said.

But excessive heat is wreaking havoc on even the world’s toughest reefs. By some estimates, the planet has lost some of its coral cover since 1950.

Record temperatures in 2017 led to the second mass bleaching event around the United Arab Emirates, which caused the loss of 66 percent of the coral coverage across eight major reefs in the southern Persian Gulf, according to John Burt, an associate professor of biology at New York University Abu Dhabi.

Terrestrial coral nurseries are much more expensive than those located in the sea, but conservationists can control water temperature and gentle exposure, creating ideal conditions for corals to thrive.

Coral Vita, which began terrestrial coral farming in the Bahamas in 2019, has focused its recovery efforts on heat-tolerant genotypes that have the highest chance of surviving in warm waters.

If corals are effectively transplanted to open water, this could serve as a model, along with some other projects, for other programs.

One option, in the future, could be to reintroduce nonnative, heat-resistant corals into ecosystems beyond the Gulf, but this could pose challenges to ecosystems and would require careful study and regulatory approval.

“We’re not at a place right now where anyone is experimenting with moving coral between basins,” Dr. Vardi said. “We’re barely there, doing it within a basin.”

“We’re in a state where we want to make sure we don’t further damage the situation,” he said. “Scientists and regulators have a very important role to play in combining smart approaches and solutions. “

Climate change is not the only threat to reefs around the Emirates. Desalination plants, which provide freshwater to Dubai residents, have also contributed to raising the Persian Gulf’s coastal water temperatures. Without intervention, the Gulf’s coastal water temperatures are expected to rise by at least 5 degrees Fahrenheit across more than 50 percent of the area by 2050, according to a 2021 study published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin on ScienceDirect, a site for peer-reviewed papers.

The UAE has also developed synthetic islands that have destroyed reefs and other ecosystems, and accelerate coastal development, contributing to pollutant and sewage runoff.

Coral recovery programs, a new field of study, have limitations. Mohammad Reza Shokri, an associate professor at Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran, Iran, said that over the past two decades he had worked to relocate corals in two coastal areas of Iran and only about 30 percent of them had survived.

Sam Teicher, Coral Vita’s co-founder, who carried out the project alongside DP World, a logistics company in Dubai, said he was encouraged by the agreement that was made at the climate summit on Wednesday, as it called for “transitioning away from fossil fuels.” Land-based coral farms were essential because they created gene banks for future preservation, but restoration projects alone were not a solution, he said.

Recently, on Abu Dhabi’s Jubail Island, tourists walked on platforms through a mangrove domain. Beyond the mangrove forest, cranes were working on a first luxury apartment structure project.

While coral recovery can become a vital component of a broader reef conservation strategy, Dr. Shokri said, the most productive way to help corals would be for governments and corporations to protect the environment.

Jenny Gross is a journalist for the Times of London and covers current affairs and issues. Learn more about Jenny Gross

Advertisement