This story is from a company that includes WBUR, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

It’s a family moment. Kids need their cereal and coffee, but you don’t have any more milk. No problem, think, the local convenience store is just a few minutes away. But if you have COVID-19 or have been exposed to the coronavirus, you should stay still.

Even this quick execution can be the explanation for why someone else is infected. But opting for others can be complicated without support.

For many, single parents or low-wage workers, for example, it’s hard to stay away because they have trouble feeding young people or paying rent. Recognizing this problem, Massachusetts includes an express role in its COVID-19 touch curriculum that is not unusual everywhere: a care resource coordinator.

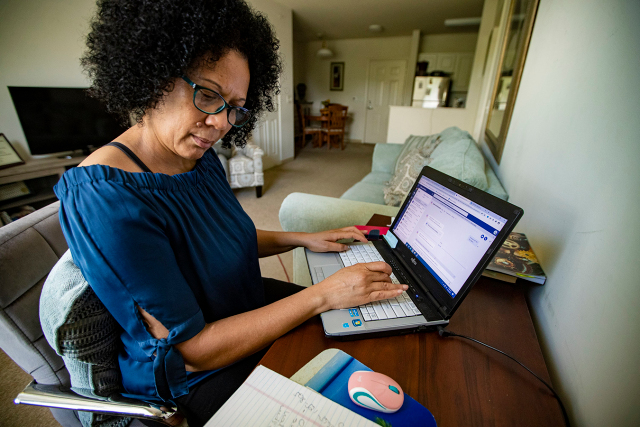

Luisa Schaeffer spends her days coordinating the resources of a densely populated immigrant in Brockton, Massachusetts.

Recently, on her first call of the day, a woman stood at her apartment door, wondering if she deserved to take this quick walk to go shopping. The woman had COVID-19. Schaeffer’s task is to help consumers make the most productive selection for the public; the assistance it provides is as fundamental and vital as delivering a jug of milk.

“That’s my priority. I have to put milk in yours immediately,” Schaeffer said.

“Most of the time, those are things that can spread the virus.”

Subscribe to KHN’s short morning report.

The woman who needed milk in one of the 8 cases referred to Schaeffer through the state government’s Community Tracing Collaborative. Contact trackers call other remote people on a daily basis because they have tested positive or quarantined because they have been exposed to the coronavirus and have to wait 14 days to see if they expand an infection. Collaboration estimates that between 10% and 15% of instances seek help. These requests are forwarded to Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators.

“Many other people are on this edge as thin as a razor, and it’s a singles-like diagnosis that can oppose them,” said John Welch, chief operating officer and associations for the Massachusetts Coronavirus Response to Partners in Health, which manages state contacts. tracking program.

He said a role like resource coordinator becomes to return others to “a sense of health, a sense of well-being, a sense of safety.”

With milk on the way, Schaeffer called a woman who needed to find a number one care doctor, schedule an appointment, and apply for Medicaid. That call in Spanish.

With his third client, Schaeffer moved to his local language, Cape-Capeal-Derian Creole. The guy at the other end of the line and his mother were in poor health and out of work. He asked for food stamps and refused. Schaeffer sent a text message to the regional head of a state workplace that organizes the program. A few minutes later, the director responded via a text message that was on the case.

Schaeffer, who has deep roots in the community, is on transitional borrowing to study collaboration with government contacts and will return to work later, helping patients perceive and stick to prescription remedies at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center.

The collaboration indicated that most requests from visitors were for food, medicines, masks and cleaning products. COVID-19 patients who are without paint for weeks or who do not have a salaried task may want help applying for unemployment or rental assistance, which is offered to qualified Massachusetts residents.

Care resource coordinators even put others in touch with legal assistance when they want to. An elderly woman was informed that she was running in the laundry room of a nursing home that she would not be paid in case of illness. Schaeffer contacted Community Tracing Collaborative’s attorney, who reminded the company that paid leave is required in poor health conditions for top employers during the pandemic.

“Then, now, everything is in place. They pay him,” Schaeffer said.

There are disorders when care resource coordinators consult others who isolate the accommodation at home. Some undocumented employees return to paintings because they’re worried about wasting their jobs. When the local food bank ran out, Schaeffer struggled to find a local grocery store to help him. Free preserves or vegetables can be like foreign cuisine for Schaeffer’s customers, some of whom are from Cape Verde and Peru. In such cases, you can contact a nutritionist and organize a cooking lesson through a convention.

“I love calls to three,” she says radiantly.

Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators have responded to more than 10,500 requests for assistance to date through the Massachusetts Contact Research Program. Demand is probably higher in cities like Brockton, with infection rates higher than in peak states and a median household income at 28.7% lower.

Massachusetts has carved out care resource coordination as a separate job in this project. But the role is not new. Local health departments routinely include what might be called support or wrap-around services when tracing contacts. With cases of tuberculosis, for example, a public health worker might make sure patients have a doctor, get to frequent appointments and have their medications.

“You can’t have one without the other,” said Sigalle Reiss, president of the Massachusetts Association of Health Officers.

Welch of Partners in Health, which advises other states on contact search, said the importance of helping a user feed and hire while citizens are isolated is getting enough attention.

“I don’t see this as a one-of-a-kind technique with other contact search systems in the United States,” he said.

Some touch-study systems that schools, employers, or states have put in the pandemic ward position only the essentials.

“They focus on: Make your case positive, locate contacts, read the script, finish, finish,” said Adriane Casalotti, director of public affairs and government at the National Association of City and County Health Officials. “And that’s not how people’s lives work.”

Casalotti stated that the function, and facilities for other remote or quarantined people, are loaded to the task of locating contacts. He is urging greater federal investment to help cover those expenses, as well as a federal extension of the paid sick leave requirement in cases of poor health, and more effective for food banks so that others exposed to the coronavirus can ensure that they do not. someone else.

“People’s lives can be complicated and complicated, so help them leave everything and all of us; we can help them succeed over the demanding situations they may face,” Casalotti said.

This story is from a company that includes WBUR, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

It’s a family moment. Kids need their cereal and coffee, but you don’t have any more milk. No problem, think, the local convenience store is just a few minutes away. But if you have COVID-19 or have been exposed to the coronavirus, you should stay still.

Even this quick execution can be the explanation for why someone else is infected. But opting for others can be complicated without support.

For many, single parents or low-wage workers, for example, it’s hard to stay away because they have trouble feeding young people or paying rent. Recognizing this problem, Massachusetts includes an express role in its COVID-19 touch curriculum that is not unusual everywhere: a care resource coordinator.

Luisa Schaeffer spends her days coordinating the resources of a densely populated immigrant in Brockton, Massachusetts.

Recently, on her first call of the day, a woman stood at her apartment door, wondering if she deserved to take this quick walk to go shopping. The woman had COVID-19. Schaeffer’s task is to help consumers make the most productive selection for the public; the assistance it provides is as fundamental and vital as delivering a jug of milk.

“That’s my priority. I have to put milk in yours immediately,” Schaeffer said.

“Most of the time, those are things that can spread the virus.”

It’s a family moment. Kids need their cereal and coffee, but you don’t have any more milk. No problem, think, the local convenience store is just a few minutes away. But if you have COVID-19 or have been exposed to the coronavirus, you should stay still.

Even this quick execution can be the explanation for why someone else is infected. But opting for others can be complicated without support.

For many, single parents or low-wage workers, for example, it’s hard to stay away because they have trouble feeding young people or paying rent. Recognizing this problem, Massachusetts includes an express role in its COVID-19 touch curriculum that is not unusual everywhere: a care resource coordinator.

Luisa Schaeffer spends her days coordinating the resources of a densely populated immigrant in Brockton, Massachusetts.

Recently, on her first call of the day, a woman stood at her apartment door, wondering if she deserved to take this quick walk to go shopping. The woman had COVID-19. Schaeffer’s task is to help consumers make the most productive selection for the public; the assistance it provides is as fundamental and vital as delivering a jug of milk.

“That’s my priority. I have to put milk in yours immediately,” Schaeffer said.

“Most of the time, those are things that can spread the virus.”

The woman who needed milk in one of the 8 cases referred to Schaeffer through the state government’s Community Tracing Collaborative. Contact trackers call other remote people on a daily basis because they have tested positive or quarantined because they have been exposed to the coronavirus and have to wait 14 days to see if they expand an infection. Collaboration estimates that between 10% and 15% of instances seek help. These requests are forwarded to Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators.

“Many other people are on this edge as thin as a razor, and it’s a singles-like diagnosis that can oppose them,” said John Welch, chief operating officer and associations for the Massachusetts Coronavirus Response to Partners in Health, which manages state contacts. tracking program.

He said a role such as resource coordinator becomes essential in getting people back to “a sense of health, a sense of wellness, a sense of security.”

With milk on the way, Schaeffer called a woman who needed to find a number one care doctor, schedule an appointment, and apply for Medicaid. That call in Spanish.

With his third client, Schaeffer moved to his local language, Cape-Capeal-Derian Creole. The guy at the other end of the line and his mother were in poor health and out of work. He asked for food stamps and refused. Schaeffer sent a text message to the regional head of a state workplace that organizes the program. A few minutes later, the director responded via a text message that was on the case.

Schaeffer, who has deep roots in the community, is on transitional borrowing to study collaboration with government contacts and will return to work later, helping patients perceive and stick to prescription remedies at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center.

The collaboration indicated that most requests from visitors were for food, medicines, masks and cleaning products. COVID-19 patients who are without paint for weeks or who do not have a salaried task may want help applying for unemployment or rental assistance, which is offered to qualified Massachusetts residents.

Care resource coordinators even put others in touch with legal assistance when they want to. An elderly woman was informed that she was running in the laundry room of a nursing home that she would not be paid in case of illness. Schaeffer contacted Community Tracing Collaborative’s attorney, who reminded the company that paid leave is required in poor health conditions for top employers during the pandemic.

“Then, now, everything is in place. They pay him,” Schaeffer said.

There are disorders when care resource coordinators consult others who isolate the accommodation at home. Some undocumented employees return to paintings because they’re worried about wasting their jobs. When the local food bank ran out, Schaeffer struggled to find a local grocery store to help him. Free preserves or vegetables can be like foreign cuisine for Schaeffer’s customers, some of whom are from Cape Verde and Peru. In such cases, you can contact a nutritionist and organize a cooking lesson through a convention.

“I love calls to three,” she says radiantly.

Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators have responded to more than 10,500 requests for assistance to date through the Massachusetts Contact Research Program. Demand is probably higher in cities like Brockton, with infection rates higher than in peak states and a median household income at 28.7% lower.

Massachusetts has made coordinating care resources a separate task in this project. But the role is not new. Local fitness facilities regularly come with what might be called auxiliary or complementary facilities when tracking contacts. In cases of tuberculosis, for example, a public fitness officer can make sure patients have a doctor, go to appointments, and get their medication.

“You can’t have one without the other,” said Sigalle Reiss, president of the Massachusetts Association of Health Officers.

Welch of Partners in Health, which advises other states on contact search, said the importance of helping a user feed and hire while citizens are isolated is getting enough attention.

“I don’t see this as a one-of-a-kind technique with other touch search systems in the United States,” he said.

Some touch-study systems that schools, employers, or states have put in the pandemic ward position only the essentials.

“They focus on: Make your case positive, locate contacts, read the script, finish, finish,” said Adriane Casalotti, director of public affairs and government at the National Association of City and County Health Officials. “And that’s not how people’s lives work.”

Casalotti stated that the function, and facilities for other remote or quarantined people, are loaded to the task of locating contacts. He is urging greater federal investment to help cover those expenses, as well as a federal extension of the paid sick leave requirement in cases of poor health, and more effective for food banks so that others exposed to the coronavirus can ensure that they do not. someone else.

“People’s lives can be complicated and complicated, so help them leave everything and all of us; we can help them succeed over the demanding situations they may face,” Casalotti said.

This story is from a company that includes WBUR, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

The woman who needed milk in one of the 8 cases referred to Schaeffer through the state government’s Community Tracing Collaborative. Contact trackers call other remote people on a daily basis because they have tested positive or quarantined because they have been exposed to the coronavirus and have to wait 14 days to see if they expand an infection. Collaboration estimates that between 10% and 15% of instances seek help. These requests are forwarded to Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators.

“Many other people are on this edge as thin as a razor, and it’s a singles-like diagnosis that can oppose them,” said John Welch, chief operating officer and associations for the Massachusetts Coronavirus Response to Partners in Health, which manages state contacts. tracking program.

He said a role like resource coordinator becomes to return others to “a sense of health, a sense of well-being, a sense of safety.”

With milk on the way, Schaeffer called a woman who needed to find a number one care doctor, schedule an appointment, and apply for Medicaid. That call in Spanish.

With his third client, Schaeffer moved to his local language, Cape-Capeal-Derian Creole. The guy at the other end of the line and his mother were in poor health and out of work. He asked for food stamps and refused. Schaeffer sent a text message to the regional head of a state workplace that organizes the program. A few minutes later, the director responded via a text message that was on the case.

Schaeffer, who has deep roots in the community, is on transitional student loan, collaborates with government contacts, and will return to work later, helping patients perceive and stick to prescription remedies at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center.

The collaboration indicated that most requests from visitors were for food, medicines, masks and cleaning products. COVID-19 patients who are out of work for weeks or who do not have a salaried task may want assistance in applying for unemployment or rental assistance, which is offered to qualified Massachusetts residents.

Care resource coordinators even put others in touch with legal assistance when they want to. An elderly woman was informed that she was running in the laundry room of a nursing home that she would not be paid in case of illness. Schaeffer contacted Community Tracing Collaborative’s attorney, who reminded the company that paid leave is required in poor health conditions for top employers during the pandemic.

“Then, now, everything is in place. They pay him,” Schaeffer said.

There are disorders when care resource coordinators consult others who isolate the accommodation at home. Some undocumented employees return to paintings because they’re worried about wasting their jobs. When the local food bank ran out, Schaeffer struggled to find a local grocery store to help him. Free preserves or vegetables can be like foreign cuisine for Schaeffer’s customers, some of whom are from Cape Verde and Peru. In such cases, you can contact a nutritionist and organize a cooking lesson through a convention.

“I love calls to three,” she says radiantly.

Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators have responded to more than 10,500 requests for assistance to date through the Massachusetts Contact Research Program. Demand is probably higher in cities like Brockton, with infection rates higher than in peak states and a median household income at 28.7% lower.

Massachusetts has made coordinating care resources a separate task in this project. But the role is not new. Local fitness facilities regularly come with what might be called auxiliary or complementary facilities when tracking contacts. In cases of tuberculosis, for example, a public fitness officer can make sure patients have a doctor, go to appointments, and get their medication.

“You can’t have one without the other,” said Sigalle Reiss, president of the Massachusetts Association of Health Officers.

Welch of Partners in Health, which advises other states on contact search, said the importance of helping a user feed and hire while citizens are isolated is getting enough attention.

“I don’t see this as a one-of-a-kind technique with other touch search systems in the United States,” he said.

Some touch-study systems that schools, employers, or states have put the pandemic canopy in position only in essence.

“They focus on: making your case positive, locating contacts, reading the script, finishing, finishing,” said Adriane Casalotti, director of public and government affairs at the National Association of City and County Health Officials. “And that’s not how people’s lives work.”

Casalotti stated that the function, and facilities for other remote or quarantined people, are loaded to the task of locating contacts. He is urging greater federal investment to help cover those expenses, as well as a federal extension of the paid sick leave requirement in cases of poor health, and more effective for food banks so that others exposed to the coronavirus can ensure that they do not. someone else.

“People’s lives can be complicated and complicated, so help them leave everything and all of us; we can help them succeed over the demanding situations they may face,” Casalotti said.

This story is from a company that includes WBUR, NPR, and Kaiser Health News.

We inspire organizations to republish our content free of charge. Here’s what we asked:

It’s important to note, not everything on khn.org is available for republishing. If a story is labeled “All Rights Reserved,” we cannot grant permission to republish that item.

Do you have any questions? Let us know [email protected]

Thank you for your interest in supporting Kaiser Health News (KHN), the country’s premier nonprofit fitness and fitness policy writing room. We distribute our journalism without fees and advertising through media partners of all sizes and in small, giant communities. We appreciate all the participation bureaucracy of our readers and listeners, and we appreciate your support.

KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). You can KHN by making a contribution to KFF, a nonprofit that is not related to Kaiser Permanente.

Click the button below the KFF donation page that will provide more information and FAQs. Thank you!