Advertising

Supported by

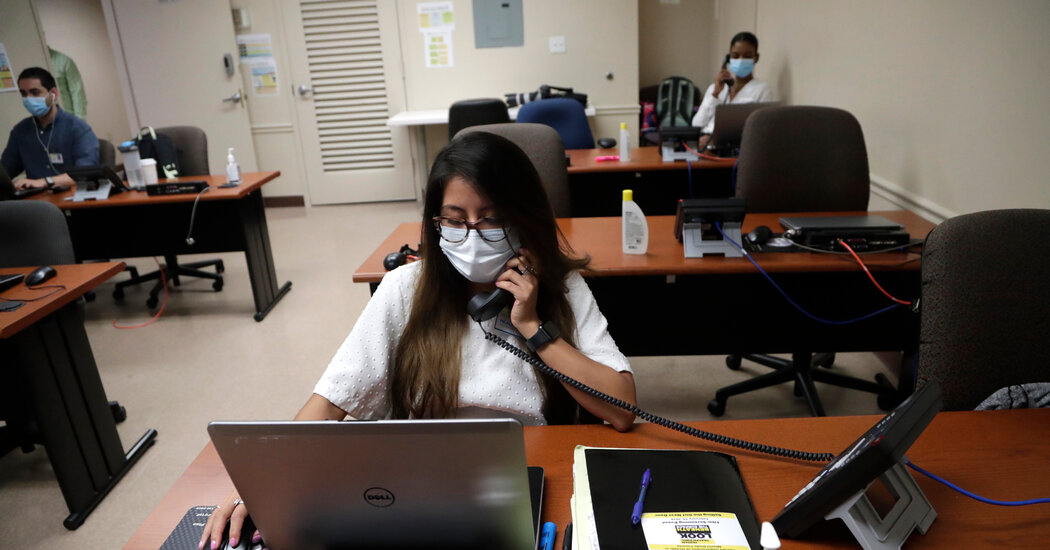

Insufficient and prolonged delays in the production of effects have hampered monitoring and hampered efforts to involve primary epidemics.

By Jennifer Steinhauer and Abby Goodnough

In Arizona’s highest population region, coronavirus is so ubiquitous that touch markers have not been successful in a fraction of those infected.

In Austin, Texas, the story is very similar. As in the case of North Carolina, where the state’s physical secretary recently told state lawmakers that its follow-up program hires external staff to keep up with a steady increase in cases, as in other states.

Florida cities, some other state where Covid-19 instances are on the rise, have a large desert case tracking component. Things are just as depressing in California. And as a component of New York City’s curriculum, staff complained of crippling problems of communication and education.

Contact research, a cornerstone of the global public fitness arsenal to reduce coronavirus, has largely failed in the United States; the ubiquity of the virus and the main delays in testing have made the formula almost useless. In some areas, giant sections of the population have refused to participate or may not even be located, making it even more difficult for fitness workers.

“We don’t do it to the point or to the extent that it deserves to be done,” said Steve Adler, mayor of Austin, echoing the prospects of many heads of state and city. “There are 3 main reasons. The first is the large number of people, the time is the delay in returning the results of the controls, the third is the spread of the disease in the community.

The purpose of touchscreen studies for Covid-19 is to succeed in others who have spent more than 15 minutes within six feet of an inflamed user and ask them to voluntarily quarantine themselves at home for two weeks, even if their check is negative. by monitoring the symptoms themselves during this period. Time. But few sales options have reported systemic success. And since the beginning of the epidemic in the U.S., states and cities have struggled to trip over the prevalence of the virus due to abnormal and infrequently rationed diagnostic controls and long delays in results.

“I think it’s easy to say that touch studies are interrupted,” said Carolyn Cannuscio, an approach specialist and associate professor of family circle medicine and network fitness at the University of Pennsylvania. “It’s damaged because a lot of parts of our prevention formula are damaged.”

Tracking the above is so far from the virus spreading to the fullest that many public fitness officials that the cash and personnel in question would spend more on other resources, such as expanding verification sites, helping schools prepare for reopening, and educating the public about masked dresses. Some public fitness experts now that at least control and touch seek to shrink in spaces where outbreaks are high. In some cases, they say the effort will possibly never succeed.

“Contact search is the tool for bad paints at the time,” said Dr. David Lakey, a former Texas state fitness commissioner who helped oversee the Ebola reaction in Dallas in 2014.

“By the time he had 10 cases here in Texas, this could have been helpful,” said Dr. Lakey, who is now the formula’s leading medical officer at the University of Texas. “But if an immediate screening is not performed, it will be very complicated in a disease in which 40% of other people are asymptomatic. It’s hard to see the benefits right now.”

Advertising