About a month ago, Colombia’s Supreme Court ordered the space arrest of former President Allvaro Uribe following allegations of witness manipulation. The abundant controversy this has triggered may not come at a worse time for Colombia, which is tebbling over the adverse effects of the coronavirus pandemic and falling oil costs in March 2020. revitalized Colombia’s important oil industry and triggered the economic miracle that saw the Andean country record some of Latin America’s most powerful expansion rates.

Basically, this includes the repression of left-wing guerrillas who, at the time of Uribe’s ascension to the Colombian post, controlled large swaths of the country. The most recent occasion follows fears that the historic 2016 peace agreement with the largest guerrilla organization, the FARC, could crumble and create greater insecurity, especially in rural areas.

It is estimated that up to 15% of FARC fighters demobilized in 2017 have re-attacked. This, along with the estimated record production of cocaine in Colombia, now the world’s largest supplier of narcotics, has led to a sharp drop in the security environment. The last left-wing guerrilla organization, the ELN, has also intensified efforts to seceo the territory of former FARC and the lucrative drug trafficking routes in its own war against the Colombian state.

These occasions saw a sharp increase in the volume of attacks on Colombia’s oil infrastructure, adding an attack in June 2020 to 31 wells in the La Cira-Infantas oil box of the national oil company Ecopetrol. While pot-mouth attacks were commonplace before the 2016 peace agreement, they had declined particularly in recent years. As a result, the growing number of pipeline bombardments is likely to disrupt Colombia’s oil industry, economically and increasingly vulnerable.

At the height of the last oil boom, crude oil and plant fuels accounted for about 5% of Colombia’s GDP, 1.5% more than in the last quarter of 2020. It is this decrease in the contribution of oil to the Colombian economy that is to blame. because of the sharp decline in expansion. This will only worsen with the COVID-19 pandemic, with Colombia among the 10 worst-affected countries in the world with more than 534,000 cases and 16,183 deaths. The IMF estimates that Colombia’s economy will contract to a peak of 8% in 2020, with an expansion of 3.3% in 2019.

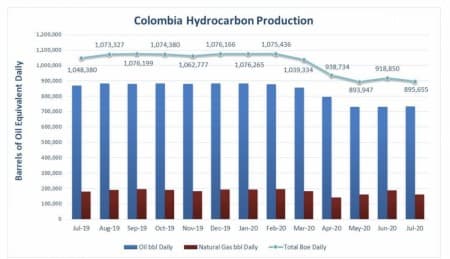

If the Outlook for the Andean country’s own oil industry deteriorates due to sharp fall in oil prices, declining production, and increased security risks, economic benefits will increase. By July 2020, Colombian oil production had fallen 15% year-over-year to a low of approximately 10 years of 734,897 barrels consistent with the day and herbal fuel had plummeted by 11% since last year to 933 million cubic feet consistent with the day.

Source: Ministry of Mines and Energy of Colombia.

Related: EIA bullish stocks rise oil prices

In early 2020, the Andean country made the decision to have just over 2 billion barrels of reserves shown, equivalent to about six years of oil production at the current rate. There have been no primary discoveries of land hydrocarbons in Colombia since 2009 and if production declines due to lack of reserves, this will have a bountiful effect on the country’s oil economy in the South American country. This underscores the urgency of Bogota attracting investment in the economicly important oil industry. At the end of 2018, President Duque said Colombia will have to double its oil reserves if the country wants to remain self-sufficient in energy.

Growing insecurity, violence and civil unrest are hampering this effort and will continue to have an effect on oil production and major exploration activities. Towards the end of 2019, Colombia, like many Latin American countries, was rocked by anti-government protests. The unrest caused by these civil unrest is far from resolved. They focus on human rights, the killing of social leaders, state-sponsored oppression, and a lack of equitable access to resources. Protests are expected to resume once the COVID-19 closure in Colombia is lifted. There is fear that Uribe’s arrest will magnify civil unrest in Colombia, even causing an armed confrontation between pro and anti-Uribe groups. This would be a devastating result for a Colombia still recovering from nearly seven decades of low-level asymmetric shock and now the deep economy has an effect on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Related: Saudi Arabia’s Oil Minister: Oil order can reach up to 97% by end of 2020

Community blockades also remain a widespread threat that may worsen after Uribe’s arrest and pilot hydraulic fracturing projects. Upstream manufacturer Gran Tierra Energy was forced to close operations and claim a force majeure case on its Surorient and PUT-7 blocks in southern Putumayo due to blockades through local farmers.

Many other people in localities where oil corporations operate oppose the industry due to the prospect of environmental damage and antagonism towards the central government of Bogota. This has been amplified through royalty reform, which has noticed that oil revenues are distributed more widely, resulting in a decrease in revenue for departments where the oil industry operates. The Constitutional Court’s 2018 ruling that referendums through local communities prohibiting oil extraction prevent energy projects have further increased regional resentment of the Andean country’s hydrocarbons sector.

The greatest security threat, particularly in the remote field where top oil corporations operate, weighs heavily on Colombia’s oil industry. Uribe’s recent detention can cause new conflicts in a country ravaged by a low-level asymmetric warfare for decades. This would have a significant deterrent effect on the urgently needed foreign investment in Colombia’s declining oil industry, causing production to decline and damaging an already fragile economy.

More maximum Oilprice.com readings:

Read this article in OilPrice.com

This story gave the impression to Oilprice.com