Advertising

Supported by

Poor water quality and dry hydrants were the main obstacles in fighting the February blaze that killed dozens of people along the country’s Pacific coast.

transcription

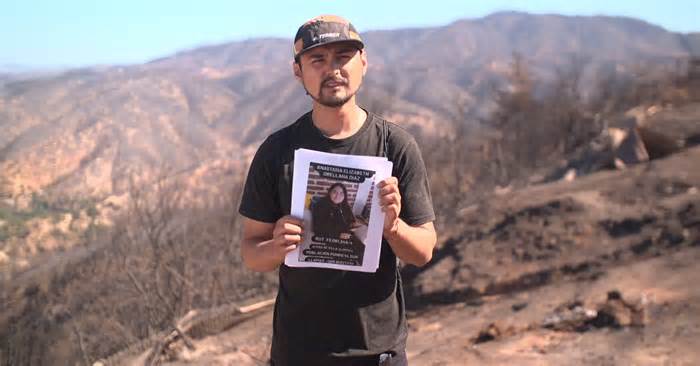

In those February videos, a Chilean firefighter recorded his desperate search for water as a forest fire swept through his city. It was the deadliest wildfire in a decade and killed at least another 134 people. It was a major typhoon of extreme weather and control errors that left thousands of people vulnerable. It also serves as a warning to cities facing the growing threats of climate change. Urban sprawl, driven by unregulated residential development, has stretched the water formula beyond what it was designed for and the scale of this wild chimney site exposed this weakness. The New York Times spoke with fire fighters and citizens in the two cities of Viña del Mar and Quilpué, who said that some hydrants on that critical day had little or no water supply. Escape routes have temporarily become bottlenecks and death traps. This crisis has shown that many cities are not prepared to face the forest fires that have become more common and more intense. Rodrigo Mundaca, one of the most fervent defenders of water rights in Chile, is currently governor of the region affected by the forest fire. Chile is one of the few countries in the world with a formula of privatized water rights. This climate catastrophe has revived an old debate in the country about unequal access to water, which does not prosper in the poorest communities. Today, some citizens who have lost their homes or enjoyed them do not find greater protection easy. Most of those who died in the wild lived in informal settlements along exposed slopes, places where water companies are not required to install hydrants. The chimney hydrant closest to Ariel Orellana’s mother’s house, in Quilpué, was a maximum of one kilometer away. She lost her mother, her husband, and her 14-year-old sister. Esval, which controls water rights in the area, has denied any wrongdoing and said its hydrant precertification likely would have been slowed due to the sudden increase in demand. “I believe that our responsibility is not at all because we are sure that the chimney hydrants were working. I sense the frustration of others. I sense that they expected something different, but we are pretty sure that what we did is 10 times more than what the regulations require of us. But Daniel Garín, a veteran volunteer chimney fighter, documented how he and his team struggled to find water to save homes at the height of the shooting. Several citizens of Quilpué are now demanding reimbursement from Esval for the damage suffered to their homes, which, they claim, is due to the lack of water in the chimney hydrants. And the country’s Public Works Ministry is investigating urgent court cases that Esval failed to supply enough water to fight the forest fire.

By Brent McDonald, Miguel Soffia and John Bartlett

Brent McDonald reported from Washington, and John Bartlett and Miguel Soffia from Quilpué and Viña del Mar in Chile.

As a fast-moving wildfire swept through the cities of Viña del Mar and Quilpué on Chile’s Pacific coast last month, flames engulfed citizens in the streets, destroying homes and disrupting the power grid. Power was cut off, communications were disrupted, and water was not successful enough on a critical line of defense: fire hydrants.

In the video report, firefighters and citizens of both cities told New York Times reporters that the lack of water had hampered efforts to save homes and prevent the blaze from advancing, forcing them to abandon parts of either city.

The wildfire, the deadliest in Chile’s history, which killed another 134 people and destroyed thousands of homes, was extinguished almost from the start, fueled by extreme weather, high winds and flammable trees.

The lack of water has worsened the situation, for firefighters and neighbors.

Chile, which is mired in a prolonged drought, faces constant water turmoil to fight forest fires in urban areas.

In the Valparaiso region, which includes Viña del Mar and Quilpué, wildfire experts say unregulated development has made cities and towns vulnerable to wildfires.

“It’s a source and a call to a problem,” said Miguel Castillo, a professor at the University of Chile’s Forest Fire Engineering Laboratory, which works with cities on wildfire prevention measures.

We are retrieving the content of the article.

Please allow javascript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience as we determine access. If you’re in Reader mode, log out and log in to your Times account or subscribe to the full Times.

Thank you for your patience as we determine access.

Already a subscriber? Sign in.

Want all the Times? Subscribe.

Advertising